CASE Seeing friends

Mr. B, age 91, presents to the emergency room (ER) for hip pain. As he is being evaluated, he asks a nurse to tell the “other people” around her to leave so that he can have privacy. As clarification, Mr. B reports visual hallucinations, which prompts the ER physician to request a psychiatry consult.

Mr. B is alert and oriented to time, place, and person when he is evaluated by the on-call psychiatry resident. He reports that he has been seeing several unusual things for the last 4 to 5 months. Asked to elaborate, Mr. B admits seeing colorful and vivid images of people around him. These people come and go as they like; rarely, they talk to him. He describes the conversations as “a constant chatter” in the background and adds that it is difficult to understand what they are talking about.

Mr. B states that he has been “seeing” a couple of people on a regular basis, and they are “sort of like my friends.” He endorses that these people often sing songs or dance for him. He states that, sometimes, these “friends” bring 3 or 4 friends and, although he could not make out their faces clearly, “they all are around me.” He describes the people he sees as “nice people” and does not report being scared or frightened by them.

Mr. B does not report paranoia, and denies command-type hallucinations. He and his family report no unusual changes in behavior in recent months. The medical history is remarkable for atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma.

Mr. B denies having any ongoing mood or anxiety symptoms. He states that he knows these people are “probably not real,” and they do not bother him and just keep him company.

What could be causing Mr. B’s hallucinations?

a) a stroke

b) late-onset schizophrenia

c) dementia

d) Charles Bonnet syndrome

The authors’ observations

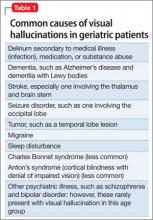

Visual hallucinations among geriatric pa-tients are a common and confusing presentation. In addition to several medical causes for this presentation (Table 1), consider Charles Bonnet syndrome in patients with visual loss, presenting as visual hallucinations with intact insight and absence of a mental illness. Other conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis include Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, schizophrenia, seizures, migraine, and stroke, including lesions of the thalamus or brain stem.

Charles Bonnet syndrome was first described by Swiss philosopher Charles Bonnet in the 18th century. He reported vivid visual hallucinations in his visually impaired grandfather (bilateral cataracts).1

It is important to recognize this syndrome because patients can present across different specialties, including psychiatry, ophthalmology, neurology, geriatric medicine, and family medicine.2 As life expectancy increases, this condition might be seen more often. It is prudent to identify, intervene, and refer as appropriate, in addition to educating patients and caregivers about the nature and course of the condition.

EVALUATION Not psychotic

Mr. B reports good sleep and appetite. He denies using alcohol or illicit drugs. He states he slipped in the bathroom the day before coming to the ER, but denies other recent falls or injuries. Other than hip pain, he has no other physical complaints. His medication regimen includes aspirin, lisinopril, lovastatin, and metoprolol.

The ER team diagnoses a hip fracture. Mr. B is transferred to the orthopedic service; the psychiatry consult team continues to follow him. Mental status examination is unremarkable other than the visual hallucinations. His speech is clear, non-pressured, with goal-directed thought processing. Mini-Mental State Examination score is 23/30 with Mr. B having difficulty with object drawing and 3-object recall. Brief cognitive examination in the ER is unremarkable.

The orthopedic team decides on conservative management of the hip fracture. There is no evidence of infection. Mr. B is afebrile with clear sensorium; complete blood cell count and normal liver function tests are normal; urinalysis and urine drug screen are negative; and chest radiography is unremarkable. CT and MRI of the head are unremarkable.

After 1 week in the hospital, Mr. B continues to experience vivid visual imagery. No signs of active infection are found. An ophthalmologist is consulted, who confirms Mr. B’s earlier diagnosis of glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration but does not recommend further treatment. Visual field test by confrontation is normal, with normal visual reflexes.

The authors’ observations

The reported prevalence of Charles Bonnet syndrome among visually impaired people varies from study to study—from as low as 0.4% to as high as 63%.3-6 The reason for such variation can be attributed to several variables:

• underdiagnosis

• misdiagnosis

• underreporting by patients because of the benign nature of the hallucinations

• patients’ reluctance to report visual hallucinations because of fear of being labeled “mentally ill.”7,8