CASE Difficulty walking

Ms. M, age 15, is a pregnant, Spanish-speaking Guatemalan woman who is brought to obstetrics triage in a large academic medical center at 35 weeks gestational age. She complains of dizziness, tinnitus, left orbital headache, and difficulty walking.

The neurology service finds profound truncal ataxia, astasia-abasia, and buckling of the knees; a normal brain and spine MRI are not consistent with a neurologic etiology. Otolaryngology service evaluates Ms. M to rule out a cholesteatoma and suggests a head CT and endoscopy, which are normal.

Ms. M’s symptoms resolve after 3 days, although the gait disturbances persist. When no clear cause is found for her difficulty walking, the psychiatry service is consulted to evaluate whether an underlying psychiatric disorder is contributing to symptoms.

What could be causing Ms. M’s symptoms?

a) malingering

b) factitious disorder

c) undiagnosed neurologic disorder

d) conversion disorder

The authors’ observations

Women are vulnerable to a variety of psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy1 that have deleterious effects on mother, baby, and family.2-6 Although there is a burgeoning literature on affective and anxiety disorders occurring in pregnancy, there is a dearth of information about somatoform disorders.

HISTORY Abandonment

Ms. M reports that, although her boyfriend deserted her after learning about the unexpected pregnancy, she will welcome the baby and looks forward to motherhood. She seems unaware of the responsibilities of being a mother.

Ms. M acknowledges a history of depression and self-harm a few years earlier, yet says she feels better now and thinks that psychiatric care is unnecessary. Because she does not endorse a history of trauma or symptoms suggesting an affective, anxiety, or psychotic illness, the psychiatrist does not recommend treatment with psychotropic medication.

At age 5, Ms. M’s parents sent her to the United States with her aunt, hoping that she would have a better life than she would have had in Guatemala. Her aunt reports that Ms. M initially had difficulty adjusting to life in the United States without her parents, yet she has made substantial strides over the years and is now quite accustomed to the country. Her aunt describes Ms. M as an independent high school student who earns good grades.

During the interview, the psychiatrist observes that Ms. M exhibits childlike mannerisms, including sleeping with stuffed toys and coloring in Disney books with crayons. She also is indifferent to her gait difficulty, pregnancy, and psychosocial stressors. Her affect is inconsistent with the content of her speech and she is alexithymic.

Ms. M’s aunt reports that her niece is becoming more dependent on her, which is not consistent with her baseline. Her aunt also notes that several years earlier, Ms. M’s nephew was diagnosed with a cholesteatoma after he presented with similar symptoms.

The combination of (1) Ms. M’s clinical presentation, which was causing her significant impairment in her social functioning, (2) the incompatibility of symptoms with any recognized neurologic and medical disease, and (3) prior family experience with cholesteatoma leads the consulting psychiatrist to suspect conversion disorder. Ms. M’s alexithymia, indifference to her symptoms, and recent abandonment by the baby’s father also support a conversion disorder diagnosis.

From a psychodynamic perspective, the ataxia appears to be her way of protecting herself from the abandonment she is experiencing by being left again to “stand alone” by her boyfriend as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States. Her regressive behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.

The authors’ observations

This is the first case of psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy described in the literature. Authors have reported on pseudotoxemia,7 hyperemesis gravidarum,8 and pesudocyesis,9 yet there is a paucity of information on psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy. Ms. M’s case elucidates many of the clinical quandaries that occur when managing psychiatric illness—and, more specifically, conversion disorder— during pregnancy. Many women are hesitant to seek psychiatric treatment during pregnancy because of shame, stigma, and fear of loss of personal or parental rights10,11; it is not surprising that emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms.

Likely diagnosis

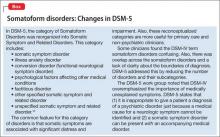

Conversion disorder is the presence of neurologic symptoms in the absence of a neurologic diagnosis that fully explains those symptoms. Conversion disorder, previously known as hysteria, is called functional neurologic symptom disorder in DSM-5 (Box).12 Symptoms are not feigned; instead, they represent “conversion” of emotional distress into neurologic symptoms.13,14 Although misdiagnosing conversion disorder in patients with true neurologic disease is uncommon, clinicians often are uncomfortable making the diagnosis until all medical causes have been ruled out.14 It is not always possible to find a psychological explanation for conversion disorder, but a history of childhood abuse, particularly sexual abuse, could play a role.14

Because of the variety of presentations, clinicians in all specialties should be familiar with somatoform disorders; this is especially important in obstetrics and gynecology because women are more likely than men to develop these disorders.15 It is important to consider that Ms. M is a teenager and somatoform disorders can present differently in adults. The diagnostic process should include a diligent somatic workup and a personal and social history to identify the patient’s developmental tasks, stressors, and coping style.15