Knotless suture anchor fixation techniques continue to evolve as efficient, low-profile options for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR).1,2 Excellent outcomes have been reported for constructs that use knotless fixation laterally, typically in suture bridge-type configurations.2-4 Early comparative biomechanical and clinical studies have also demonstrated equivalent results for all-knotless versus conventional constructs for arthroscopic RCR.5-10 Given the increased use and availability of multiple implant designs, it is important to supplement our clinical knowledge of these devices with laboratory studies delineating the biomechanical properties of the anchors that are used to help guide appropriate clinical use of the implants in specific patient populations.

Several biomechanical studies have shown suture slippage to be the weak but crucial link in the design of knotless anchors and the most likely mode of in vivo failure.11,12 Other studies have demonstrated frequent anchor dislodgement from bone, but these analyses involved use of elderly cadaveric specimens and relatively high-force testing protocols.12,13 Because suture-retention force may have exceeded anchor resistance to pullout (imparted by weak cadaveric bone in such biomechanical settings), the focus on suture-retention properties was limited.11 It is thought that, in clinical practice, the majority of patients who undergo RCR tend not to generate the high forces (relative to resistance to bone pullout) used to cause the anchor pullouts observed in biomechanical studies, particularly in the early postoperative setting.11-15 Cadaveric testing, however, often involves use of specimens with diminished bone mineral density (BMD), relative to age, because of the illness and other factors leading to death and donation.

Using a novel testing apparatus, we isolated, analyzed, and compared suture slippage in 2 anchor designs, one with entirely press-fit suture clamping and the other reliant on an intrinsic suture-locking mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Six human cadaveric proximal humeri specimens were used for this biomechanical study. Mean (SD) age was 53.3 (5.7) years (range, 46-59 years). Middle-aged specimens were used in order to best represent the quality of bone typically encountered in RCR surgery. To approximate tissue in clinical use, we used fresh-frozen cadaver tissue. Specimens were maintained at –20°C until about 24 hours before use and then were thawed to room temperature for testing. Specimens were included only if they had a completely intact humeral head and no prior surgery or hardware placement. Before instrumentation, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry with a QDR-1000 scanner (Hologic) was used to determine BMD of all proximal humeri.

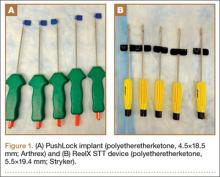

Two knotless suture anchors were compared: PushLock (4.5×18.5 mm; Arthrex) and ReelX STT (5.5×19.4 mm; Stryker). These anchors have multiple surgical indications (including RCR), allow patient-specific tissue tensioning, and use polyetheretherketone eyelets. The clamping force for PushLock depends entirely on the interference fit achieved for the suture between the outside of the anchor and the surrounding trabecular/cortical bone after device insertion, whereas the suture in ReelX is secured within the anchor shaft entirely by an internal ratchet-locking mechanism.

For anchor insertion, shoulders were dissected down to the greater tuberosity of the proximal humerus, and all implants were inserted (by a fellowship-trained surgeon in accordance with manufacturer guidelines) at a 25° insertion angle with manufacturer-supplied instruments. One anchor of each type (Figure 1) was inserted into the center of the rotator cuff footprint on the greater tuberosity of each specimen. Anterior and posterior positions were randomized, and an anchor from the other group was inserted into the matching location on the contralateral matched-pair specimen. In all instances, distance between the anterior and posterior anchors was 2 cm, and anchors were placed midway between the articular margin and the lateral edge of the greater tuberosity (Figure 2). Two strands of size 2 ultrahigh-molecular-weight–polyethylene Force Fiber (Stryker) were loaded into all anchors.

A custom urethane fixture was secured over the center of each anchor to allow testing to focus on suture slippage by minimizing anchor migration (Figure 3). The small aperture of this device allowed suture tails to pass freely through the center of the fixture but prevented disengagement and proximal migration of the suture anchor from the underlying bone through contact of the urethane fixture with the anchor perimeter. Any system deformation observed during testing was restricted to the suture and/or the anchor’s suture-locking mechanism. Testing fixtures also oriented the suture anchor coaxial with the axis of tension, creating a worst-case loading scenario (Figure 3).

PushLock implants were inserted with 5 pounds of tension, as indicated, using a manufacturer-supplied suture tensioner, and ReelX devices were inserted and locked with 2 full rotations, as specified by the manufacturer. After one end of each suture was cut, as would be done in vivo, the 2 other suture ends, which would have been part of the RCR in vivo, were tied together to form an 8-cm circumference loop that was brought through the urethane fixture. Humeri were then mounted in a materials testing system (MTS 810; MTS Systems) servohydraulic load frame, and the suture loop was passed around a cross-bar on the actuator of the testing device. A mechanical testing protocol consisting of modest repetitive forces was carefully chosen to simulate expected activity during rehabilitation after RCR.15 In this protocol, a 60-second preload of 10 N was followed by tensile loading between 10 N and 90 N at a frequency of 0.5 Hz for 500 cycles.15 Cycle duration at 3 mm and 5 mm of suture slippage (threshold for clinical failure) was recorded.12,16,17 In addition, suture slippage was measured after 1, 10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 cycles. The first 5 test cycles were not counted in the analysis to control for initial knot slippage. Finally, after completion of dynamic testing, samples were loaded at a displacement rate of 0.5 mm/s for tension-to-failure testing in the custom fixtures. Maximum failure load, stiffness, and failure mode were recorded. Ultimate failure was defined as suture breakage or gross suture slippage.