Biceps tendon testing should also be performed to help elicit signs of labral pathology. The Speed test is performed by placing a downward force on the patient’s arm, which is held in 90° forward elevation, and with elbows in extension and forearm in supination. Pain in the long head of the biceps tendon is considered a positive sign and suggestive of SLAP lesion. Although not commonly found in these athletes, external impingement should also be elicited through both the Neer test and the Hawkins test. In the Neer test, the patient’s arm is brought to maximal forward elevation with the forearm supinated and elbow extended, while the scapula is stabilized by the examiner. Pain in the shoulder indicates a positive examination. In the Hawkins test, the patient’s arm is brought into a position of forward elevation, internal rotation, and elbow flexion. The arm is then further internally rotated, and shoulder pain defines a positive examination.

Any of these findings can be concomitant with scapular dyskinesis. Moreover, symptoms related to internal impingement may be exacerbated by concomitant scapular pathology, and therefore proper assessment of scapulothoracic motion must also be performed.

4. Scapulothoracic examination

Motion coupled between the scapula and the rest of the arm (scapular rhythm) allows for efficient use of the shoulder girdle. The scapula helps transfer the force generated by the core so that the hand can efficiently deliver it. Therefore, scapular pathology (or dyskinesis) results in inefficient functioning of the arm, which can be especially debilitating in an overhead athlete.

Scapular assessment begins with visual inspection of the patient, typically from the posterior view, which allows for assessment of the resting position of the scapula. Evidence of prominence of the medial or inferomedial border, coracoid malposition (or pain on palpation), or general scapular malposition should be noted. On active ROM, as the patient forward-elevates the arm, any asymmetric prominence of the inferomedial border of the scapula should be noted. Such asymmetry may indicate underlying scapular dyskinesis. In another important test, the lateral scapular slide test (described by Kibler5), the distance from the inferomedial angle of the scapula to the thoracic spine should be measured for both sides and in 3 difference positions, noting any asymmetry between the affected and nonaffected sides. These 3 positions (Figures 4A–4C) are with arms at side, with hands on hips (internal rotation of humerus in 45° abduction), and in 90° of shoulder abduction. Last, medial and lateral scapular winging—caused by long thoracic nerve and spinal accessory nerve pathology, respectively—can be detected by asking the patient to do a “push-up” against the wall while the examiner views from posterior.

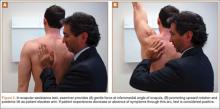

After assessment of scapular position at rest and through motion, a series of provocative maneuvers6 may aid in the diagnosis of scapular dyskinesis. The first maneuver is the scapular assistance test, in which the examiner provides a gentle force at the inferomedial angle of the scapula, promoting upward rotation and posterior tilt as the patient elevates the arm (Figures 5A, 5B). If the patient experiences a decrease or absence of symptoms through this arc, the test is considered positive. The second maneuver is the scapular retraction test, in which strength testing of the supraspinatus is performed before and after retraction stabilization of the scapula. In the baseline state, the strength of the supraspinatus is tested in standard fashion, with resisted elevation of the internally rotated and abducted arm. The strength is then tested with the scapula stabilized in retraction (the examiner medially stabilizes the scapula). With scapular stabilization, an increase in strength or a decrease in symptoms is considered a positive test.

5. Neurovascular examination

It is essential to perform a comprehensive neurovascular examination in all overhead athletes. This includes basic cervical spine testing for any motor or sensory deficits, along with assessment of scapular winging to detect long thoracic or spinal accessory nerve palsy for medial and lateral winging, respectively. Although neurovascular injury may be a rare finding in the overhead athlete, a detailed examination must still be performed to rule it out.

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Thoracic syndrome is a compressive neuropathy of nerves and vasculature exiting the thorax and entering the upper extremity. Common symptoms include pain and tingling (sometimes vague) in the neck and upper extremity. These symptoms may be positional as well.

Diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome begins with visual inspection of the involved upper extremity, noting atrophy or asymmetry. Weakness may also be present. Additional provocative maneuvers can be used to detect decrease or loss of pulses, along with reproduction of symptoms, during a provocative maneuver with subsequent return of pulses and resolution of symptoms after the maneuver is completed.