Distal radius fractures constitute 15% of all extremity fractures and are the most common upper extremity fractures.1-3 The incidence of distal radius fractures is continuing to escalate because of the expanding elderly population and concurrent increase in osteoporosis.3,4 In addition, open reduction and internal fixation with a volar locking plate for distal radius fractures are more commonly being performed by general orthopedists, who may not perform these surgeries frequently. Surgically treated patients experience less time immobilized and have a higher chance of regaining previous functional status.2 In a commonly used technique, volar fixed-angle plating is used to stabilize the distal radius. With the rising popularity of this method, more patients are having postoperative complications.1,3,5,6 Extensor tendon irritation and attritional rupture constitute up to 50% of all complications stemming from volar plating of the distal radius.1

Volar plate fixation of the distal radius was originally designed to decrease postoperative tendon complications by preventing the flexor and extensor tendons from coming into direct contact with the surgically placed plates and/or screws.1 This technique places the volar plate under the belly of the pronator quadratus muscle. Shielding the flexor tendons, the pronator quadratus can prevent the volar plate from causing flexor tendon attrition. This shielding does not occur on the dorsal side of the wrist because the extensor tendons are in full contact with the dorsal radius. As such, volar fixation gained in popularity on the premise of preventing extensor tendon complications by directly avoiding the dorsal compartment.1,7

The most common complication of volar plating ironically involves the dorsal compartment.1,7 The typical distal radius fracture occurs when a fall on an outstretched hand results in significant dorsal comminution. In these cases, it can be difficult to judge the appropriate screw length, as the depth gauge does not have an intact cortex to hook. There is the temptation to use intraoperative fluoroscopy and the depth gauge to estimate screw lengths at the distal radius, especially in cases in which a surgeon may not perform this type of surgery often. More specifically, use of a lateral image to gauge the appropriate length for screws may be tempting, but a false estimate is possible.

Screw prominence on the dorsal cortex may be caused by the complex geometry of the distal radius. This geometry is produced by the Lister tubercle and its adjacent groove for the extensor pollicis longus.7 The dorsal shape of the distal radius is a dome or dihedral with the thickest part at the Lister tubercle. The dihedral shape may hide possible dorsal screw prominence on a lateral radiograph, but screw prominence can be appreciated with computed tomography (CT) (Figures 1, 2).

We conducted a study to determine if and where screw prominence occurs, and in what amount, to establish general guidelines for screw depth based on lateral radiographs. We also wanted to be able to highlight the potential source of postoperative complications.

Materials and Methods

Twelve preserved cadaveric forearms were used for this study. Two sets of arms were paired, and the other arms came from different cadavers. In total, 5 male arms (3 left, 2 right) and 7 female arms (5 left, 2 right) were used.

The arms were harvested using a bone saw to cut through the humerus just proximal to the epicondyles, keeping the ulna and radius completely intact. Each arm was examined by the naked eye and by fluoroscopy to determine if any significant anatomical or traumatic variations in the distal radius were present. None showed any abnormal variation.

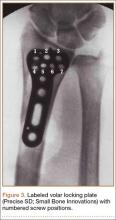

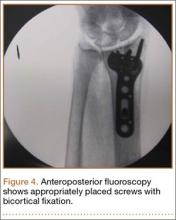

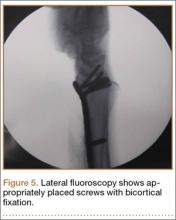

The flexor tendons and volar structures were removed to allow easy visualization and access to the distal radius. The volar locking plates (Precise SD; Small Bone Innovations) were positioned to the best anatomical and radiographic fit and secured with a proximal and distal Kirschner wire (Figure 3). A single cortical screw was placed through the shaft for compression. All 7 distal holes were drilled bicortically using an appropriately sized 2.0-mm drill and the standard block drill guide. A depth gauge was used in concordance with fluoroscopy to estimate the distance between cortices and appropriate screw lengths for each hole. A standard lateral view was used to determine the depth based on aligning the depth gauge at the dorsal cortex. The hook was not used to hook the dorsal cortex, as typically the dorsal cortex is severely comminuted and unavailable for measurement. Next, all 7 locking screws of premeasured length were secured into their respective holes. Anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique (forearm supinated and pronated 45°) radiographs were obtained to visualize screw placement and possible dorsal screw prominence (Figures 4-6).8 The extensor tendons and dorsal structures were then dissected away to expose any violation of the dorsal compartments, and calipers were used to measure absolute dorsal screw prominence and the depth of the Lister tubercle (Figure 7).