Interscalene brachial plexus anesthesia is commonly used for arthroscopic and open procedures of the shoulder. This regional anesthetic targets the trunks of the brachial plexus and anesthetizes the area about the shoulder and proximal arm. Its use may obviate the need for concomitant general anesthesia, potentially reducing the use of postoperative intravenous and oral pain medication. Furthermore, patients often bypass the acute postoperative anesthesia care unit and proceed directly to the ambulatory unit, permitting earlier hospital discharge. Previous reports in the literature have demonstrated higher rates of neurologic, cardiac, and pulmonary complications from this procedure; in particular, the incidence of pneumothorax was reported as high as 3%.1 Techniques to localize the nerves, such as electrical nerve stimulation and, more recently, ultrasound guidance, have reduced these complication rates.2,3 Successful administration of the block has been shown to result in satisfactory postoperative pain relief.2 However, ultrasound-guided interscalene nerve blocks remain operator-dependent and complications may still occur.

We report a case of tension pneumothorax after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and subacromial decompression with an ultrasound-guided interscalene block. Immediate recognition and treatment of this complication resulted in a good clinical outcome. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman presented with 3 months of right shoulder pain after a fall. Examination was pertinent for weakness in forward elevation and positive rotator cuff impingement signs. She remained symptomatic despite a course of nonsurgical management that included cortisone injections and physical therapy. Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulder showed a full-thickness supraspinatus tear with minimal fatty atrophy. After a discussion of her treatment options, she elected to undergo an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with subacromial decompression. An evaluation by her internist revealed no pertinent medical history apart from obesity (body mass index, 36). Specifically, there was no reported history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. She denied any prior cigarette smoking.

The patient was evaluated by the regional anesthesia team and was classified as a class 2 airway. An interscalene brachial plexus block was performed using a 2-inch, 22-gauge needle inserted into the interscalene groove. Using an out-of-plane technique under direct ultrasound guidance, 30 mL of 0.52% ropivacaine was injected. The block was considered successful, and no complications, such as resistance, paresthesias, pain, or blood on aspiration, were noted during injection. The patient had no complaints of chest pain or shortness of breath immediately afterward, and all vital signs were stable throughout the procedure.

The patient was brought to the operating room and placed in the beach-chair position. Induction for general anesthesia was started 15 minutes after the regional anesthetic, with 2 intubation attempts necessary because of poor airway visualization. After placement of the endotracheal tube, breath sounds were noted to be equal bilaterally. The arthroscopic procedure consisted of double-row rotator cuff repair, subacromial decompression, and débridement of the glenohumeral joint for synovitis, using standard arthroscopic portals. There were no difficulties with trocar placement, and bleeding was minimal throughout the case. The total surgical time was 150 minutes and a pump pressure of 30 mm Hg was maintained during the arthroscopy.

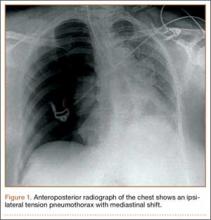

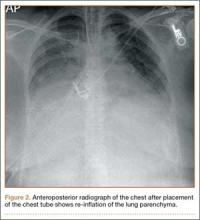

Within the first 60 minutes of the start of the arthroscopic procedure, the patient was noted to be intermittently hypotensive with mean arterial pressure (MAP) ranging from the 30s to 130s mm Hg and pulse in the 70 to 80 beats/min range. FiO2 in the 85% to 95% range was maintained throughout the procedure. During that time, 50 μg phenylephrine was administered on 4 separate occasions to maintain her blood pressure. The labile blood pressure was attributed by the anesthesiologist to the beach-chair position. During an attempted extubation upon conclusion of the surgery, the patient became hypotensive with MAP that ranged from the 40s to 60s mm Hg and tachycardic to 90 beats/min. The oxygen saturation was in the low 90s and tidal volume was poor. Absent lung sounds were noted on the right chest. An urgent portable chest radiograph showed a large right-sided tension pneumothorax with mediastinal shift (Figure 1). After an immediate general surgery consultation, a chest tube was placed in the operating room. The patient’s vital signs improved and a repeat chest radiograph revealed successful re-expansion of the lung (Figure 2). She was transferred to the acute postoperative anesthesia care unit and extubated in the intensive care unit later that day.

The patient’s chest tube was removed 2 days later and she was discharged home on hospital day 5 with a completely resolved pneumothorax. She was seen 1 week later in the office for a postoperative visit and reported feeling well without chest pain or shortness of breath.