With an incidence of 75,000 per year in the United States alone, fractures of the tibial shaft are among the most common long-bone fractures.1 Diaphyseal tibial fractures present a unique treatment challenge because of complications, including nonunion, malunion, and the potential for an open injury. Intramedullary fixation of these fractures has long been the standard of care, allowing for early mobilization, shorter time to weight-bearing, and high union rates.2-4

The classic infrapatellar approach to intramedullary nailing involves placing the knee in hyperflexion over a bump or radiolucent triangle and inserting the nail through a longitudinal incision in line with the fibers of the patellar tendon. Deforming muscle forces often cause proximal-third tibial fractures and segmental fractures to fall into valgus and procurvatum. To counter these deforming forces, orthopedic surgeons have used some novel surgical approaches, including use of blocking screws5 and a parapatellar approach that could be used with the knee in semi-extended position.6 Anterior knee pain has been reported as a common complication of tibial nailing (reported incidence, 56%).7 In a prospective randomized controlled study, Toivanen and colleagues8 found no difference in incidence of knee pain between patellar tendon splitting and parapatellar approaches.

Techniques have been developed to insert the nail through a semi-extended suprapatellar approach to facilitate intraoperative imaging, allow easier access to starting-site position, and counter deforming forces. Although outcomes of traditional infrapatellar nailing have been well documented, there is a paucity of literature on outcomes of using a suprapatellar approach. Splitting the quadriceps tendon causes scar tissue to form superior to the patella versus the anterior knee, which may reduce flexion-related pain or kneeling pain.9 The infrapatellar nerve is also well protected with this approach.

We conducted a study to determine differences in functional knee pain in patients who underwent either traditional infrapatellar nailing or suprapatellar nailing. We hypothesized that there would be no difference in functional knee scores between these approaches and that, when compared with the infrapatellar approach, the suprapatellar approach would result in improved postoperative reduction and reduced intraoperative fluoroscopy time.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by our institutional review board. We searched our level I trauma center’s database for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 27759 to identify all patients who had a tibial shaft fracture fixed with an intramedullary implant between January 2009 and February 2013. Radiographs, operative reports, and inpatient records were reviewed. Patients older than 18 years at time of injury and patients with an isolated tibial shaft fracture (Orthopaedic Trauma Association type 42 A-C) surgically fixed with an intramedullary nail through either a traditional infrapatellar approach or a suprapatellar approach were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were required fasciotomy, Gustilo type 3B or 3C open fracture, prior knee surgery, additional orthopedic injury, and preexisting radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease.

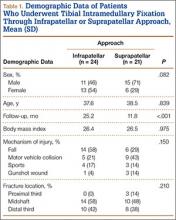

In addition to surgical approach, demographic data, including body mass index (BMI), age, sex, and mechanism of injury, were documented from the medical record. Each patient was contacted by telephone by an investigator blinded to surgical exposure, and the 12-item Oxford Knee Score (OKS) questionnaire was administered (Figure). Operative time, quality of reduction on postoperative radiographs, and intraoperative fluoroscopy time were compared between the 2 approaches. We determined quality of reduction by measuring the angle between the line perpendicular to the tibial plateau and plafond on both the anteroposterior and lateral postoperative radiographs. Rotation was determined by measuring displacement of the fracture by cortical widths. The infrapatellar and suprapatellar groups were statistically analyzed with an unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. Categorical variables between groups were analyzed with the χ2 test or, when expected values in a cell were less than 5, the Fisher exact test.

We then conducted an a priori power analysis to determine the appropriate sample size. To detect the reported minimally clinically important difference in the OKS of 5.2,10 estimating an approximate 20% larger patient population in the infrapatellar group, we would need to enroll 24 infrapatellar patients and 20 suprapatellar patients to achieve a power of 0.80 with a type I error rate of 0.05.11 This analysis is also based on an estimated OKS standard deviation of 6, which has been reported in several studies.12,13

Results

We identified 176 patients who had the CPT code for intramedullary fixation of a tibial shaft fracture between January 2009 and February 2013. After analysis of radiographs and medical records, 82 patients met the inclusion criteria. Thirty-six (45%) of the original 82 patients were lost to follow-up after attempts to contact them by telephone. One patient refused to participate in the study. Twenty-four patients underwent traditional infrapatellar nailing, and 21 patients had a suprapatellar nail placed with approach-specific instrumentation. Nine patients had an open fracture. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of sex, age, BMI, mechanism of injury, or operative time (Table 1). There was also no difference (P = .210) in fracture location between groups (0 proximal-third, 14 midshaft, 10 distal-third vs 3 proximal-third, 10 midshaft, 8 distal-third). Mean age was 37.6 years (range, 20-65 years) for the infrapatellar group and 38.5 years (range, 18-68 years) for the suprapatellar group (P = .839). Mean follow-up was significantly (P < .001) shorter for the suprapatellar group (12 mo; range, 3-33 mo) than for the infrapatellar group (25 mo; range, 4-43 mo).