Compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow, also referred to as cubital tunnel syndrome (CuTS), is the second most common peripheral nerve compression syndrome in the upper extremity.1,2 Although the ulnar nerve can be compressed at 5 different sites, including arcade of Struthers, medial intermuscular septum, medial epicondyle, and deep flexor aponeurosis, the cubital tunnel is most commonly affected.3 Patients typically present with paresthesias in the fourth and fifth digits and weakness of hand muscle intrinsics. Activity-related pain or pain at the medial elbow can also occur in more advanced pathology.4 It is estimated that conservative therapy fails and surgical intervention is required in up to 30% of patients with CuTS.1 Surgical approaches range from in situ decompression to transposition techniques, but there is no consensus in the orthopedic community as to which technique offers the best results. In a 2008 meta-analysis, Macadam and colleagues5 found no statistical differences in outcomes among the various surgical approaches. Nevertheless, subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve at the elbow is a popular option.6

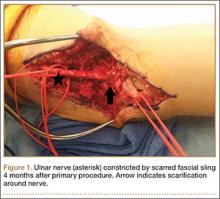

Despite the widespread success of surgical intervention for CuTS, persistent or recurrent pain occurs in 9.9% to 21.0% of cases.7-10 In addition, several investigators have cited perineural scarring as a major cause of recurrent symptoms after primary surgery.11-14 Filippi and colleagues11 noted that patients who required reoperation after primary anterior transposition had “serious epineural fibrosis and fibrosis around the transposed ulnar nerve.” At our institution, we have similarly found that scarring of the fascial sling around the ulnar nerve led to recurrence of CuTS within 4 months after initial surgery (Figure 1).

We therefore prefer to use a vascularized adipose flap to secure the anteriorly transposed ulnar nerve. This flap provides a pliable, vascularized adipose environment for the nerve, which helps reduce nerve adherence and may enhance nerve recovery.15 In the study reported here, we retrospectively reviewed the long-term outcomes of ulnar nerve anterior subcutaneous transposition secured with either an adipose flap or a fascial sling. We hypothesized that patients in the 2 groups (adipose flap, fascial sling) would have equivalent outcomes.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we reviewed the medical and surgical records of 104 patients (107 limbs) who underwent transposition of the ulnar nerve secured with either an adipose flap (27 limbs) or a fascial sling (80 limbs) over a 14-year period. The fascial sling cohort was used as a comparison group, matched to the adipose flap cohort by sex, age at time of surgery, hand dominance, symptom duration, and length of follow-up (Table 1). Patients were indicated for surgery and were included in the study if they had a history and physical examination consistent with primary CuTS, symptom duration longer than 1 year, and failed conservative management, including activity modification, night splinting, elbow pads, occupational therapy, and home exercise regimen. Electrodiagnostic testing was used at the discretion of the attending surgeon when the diagnosis was not clear from the history and physical examination. All fascial sling procedures were performed at our institution by 1 of 3 fellowship-trained hand surgeons, including Dr. Rosenwasser. The adipose flap modification was performed only by Dr. Rosenwasser. Of the 27 patients in the adipose flap group, 23 underwent surgery for primary CuTS and were included in the study; the other 4 (revision cases) were excluded; 1 patient subsequently died of a cause unrelated to the surgical procedure, and 6 were lost to follow-up. Of the 80 patients in the fascial sling group, 30 underwent surgery for primary CuTS; 5 died before follow-up, and 8 declined to participate.

Thirty-three patients (16 adipose flap, 17 fascial sling) met the inclusion criteria. Of the 16 adipose flap patients, 15 underwent the physical examination and completed the questionnaire, and 1 was interviewed by telephone. Similarly, of the 17 fascial sling patients, 15 underwent the physical examination and completed the questionnaire, and 2 were interviewed by telephone. There were no bilateral cases. Conservative management (activity modification, night splinting, elbow pads, occupational therapy, home exercise) failed in all cases.

A trained study team member who was not part of the surgical team performed follow-up evaluations using objective outcome measures and subjective questionnaires. Patients were assessed at a mean follow-up of 5.6 years (range, 1.6-15.9 years). Patients completed the DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand) questionnaire16 and visual analog scales (VASs) for pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness in the ulnar nerve distribution. They also rated the presence of night symptoms that were interfering with sleep. The Modified Bishop Rating Scale (MBRS) was used to quantify patient self-reported data17,18 (Figure 2). The MBRS measures overall satisfaction, symptom improvement, presence of residual symptoms, ability to engage in activities, work capability, and subjective changes in strength and sensibility.