Phase II (Throwing off the Mound). Once a pitcher completes Phase 1 without pain or complications, he is ready to begin throwing off the mound. The same principle remains in Phase 2: pitchers must complete each step pain-free before advancing to the next stage. Pitchers should first throw fastballs at 50% effort and progress to 75% and 100% effort. Because athletes often find it difficult to gauge their own effort, it is important to emphasize the importance of strictly adhering to the program. Fleisig and colleagues13 studied healthy pitchers’ ability to estimate their throwing effort. When targeting 50% effort, athletes generated ball speeds of 85% with forces and torque approaching 75% of maximum. A radar gun may be valuable in guiding effort control.

As the player advances through Phase 2, he will increase the volume of pitches as well as the effort in a gradual manner. The player may introduce breaking ball pitches once he demonstrates the ability to throw light batting practice. Phase 2 concludes with the pitcher throwing simulated games, progressing by 15 throws per workout.

Hitting

Biomechanics Overview

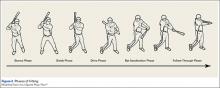

The mechanics of hitting a baseball can be broken down into 6 phases: the preparatory phase, stance phase, stride phase, drive phase, bat acceleration phase, and follow-through phase.14 While progressing through a return-to-play protocol, it is important to understand and teach the player proper swing mechanics during each phase in order to minimize the risk of re-injury (Figure 2).

The preparatory phase occurs as the player positions himself into the batter’s box. This phase is highly individualized, depending on each player’s personal preference. Though significant variability in approach exists, there are 3 basic stances a player can take in preparation to bat. In the closed stance, the batter’s front foot is positioned closer to the plate than the back foot. A more popular stance is the open stance, where the player’s back foot is placed closer to the plate than the front foot. The square batting stance is the most common stance. This stance is where both feet are in line with the pitcher and parallel with the edge of the batter’s box. Most authors agree that the square stance is the optimal position because it provides batters the best opportunity to hit pitches anywhere in the strike zone and limits compensatory or extra motion to their swing.15

Once the player begins the swing, he has entered the loading period, which is divided into the stance, stride, and drive phases. The loading period, also known as coiling or triggering, begins as the athlete eccentrically stretches agonist muscles and rotates the body away from the incoming ball. The elastic energy stored during this stretching is released during the concentric contraction of the same muscles and transferred through the entire kinetic chain as different segments of the body are rotated; it culminates in effort directed at hitting the baseball.16

In each phase of the loading period, certain critical motions should be monitored and corrected in order to return the player to his previous level of competition. Stride length has been shown to be critical in the timing of a batter’s swing. A short stride length can cause early initiation of the swing, while a longer stride can produce delayed activation of hip rotation. As the player enters the drive phase, he should have increased elbow flexion in the back elbow compared to the front elbow. The bat should be placed at a position approximately 45° in the frontal plane, and the bat should bisect the batter’s helmet. The back elbow should be down, both upper extremities should be positioned close to the hitter’s body, and the proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands should align on the handle of the bat. Athletic trainers and coaches should be aware that subtle compensations due to deficits during these movements could cause injury during the swing by disrupting the body’s natural motion.

The bat acceleration phase occurs from maximal bat loading through striking the ball. In this time, the linear force that has been exerted by the player must be transferred into rotational force through the trunk and upper extremities. When the lead leg contacts the ground, the player has created a closed kinetic chain, where the elastic energy gathered during the loading period is used to produce segmental rotation beginning in the hips and rising through the trunk and out to the arms and hands, finally producing contact with the baseball.16 To produce effective bat velocity, each segment must rotate in a sequential manner. If the upper extremities reach peak velocity before any lower segment, then the player has lost the ability to efficiently transfer kinetic energy up the kinetic chain.