Results

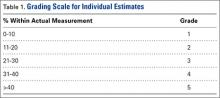

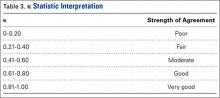

The 10 participants’ estimates differed significantly (P < .0006) from the calibrated measurements, as did residents’ estimates (P < .0025) and fellowship-trained hand surgeons’ estimates (P < .0002). Estimates were scored 1 to 5 on the basis of proximity to calibrated measurements (Table 1). Thus, more accurate estimates received lower scores. Individual estimates were then scored and stratified into groups for comparison. Third-year residents were the most accurate residents, and there was no difference in accuracy between residents and fellowship-trained hand surgeons. These results are listed in Table 2. Once overall and grouped accuracy was analyzed, κ statistics were calculated to compare interobserver and intraobserver reliability. Overall interobserver agreement was poor for both initial readings (κ = 0.16) and secondary readings (κ = 0.16), indicating poor strength of agreement between individuals both initially and secondarily. Table 3 presents the κ interpretations. There was moderate overall intraobserver agreement (45.83%), indicating participants’ secondary estimates agreed with their primary estimates 46% of the time. Fellowship-trained hand surgeons and first-year residents had the highest intraobserver agreement (50.0%). These results are listed in Table 4.

Discussion

Accurate assessment of partial flexor tendon lacerations is difficult and subjective. There is no standardized method for determining the extent of injury, regardless of whether the evaluation is performed in an emergency department or in the operating room. As McCarthy and colleagues7 noted in their survey of ASSH members, naked eye assessment was by far the most popular means of estimating percentage injured in partial lacerations, and only 10% of the survey respondents used intraoperative measuring devices. Our study showed that participants agreed with one another less than 50% of the time when evaluating injuries without the aid of measuring devices. In addition, interobserver agreement in this study was about 50%, highlighting the difficulty in making an accurate and reproducible assessment.

In a study of canine flexor tendons, McCarthy and colleagues9 found calipers are inaccurate as well and do not provide a reliable means of assessing partial flexor tendon lacerations. They compared caliper measurements with laser micrometer measurements, and the differences averaged 29.3%. They suggested that methods for calculating loss of CSA and for creating precise lacerations must be developed in order to evaluate treatments. One such method is the “tenotome,” devised by Hitchcock and colleagues10: A device with standard scalpel blades is used to make uniform lacerations in tendons by leaving a constant area of the tendon intact, regardless of the size or shape of the original tendon. Measurements made with calipers or rulers assume the tendon has a regular ellipsoid shape, but in reality the shape is a double-ellipse, particularly within the flexor sheath.

Dobyns and colleagues11 observed that changes in CSA size can be related to changes in the size of the bundle pattern of the tendon. They found that, on average, the radial bundle comprised about 60% of the total CSA of the tendon. This finding was clarified by Grewal and colleagues.12 Using histologic sections of tendons plus photomicrographs, they determined that, in zone II of the index and small fingers, the ulnar bundle had an area consistently larger than 50% and the radial bundle less than 50% of the total tendon area. In the ring and middle fingers, the areas of both bundles were almost 50% of the total tendon area. The authors suggested that, using this bundle pattern theory of injury, surgeons could more accurately evaluate the extent of injury with the naked eye.

One of the questions that prompted our study is how reliable is the information a surgeon receives regarding a partial flexor tendon injury evaluated by someone else in another setting. What is done with this information is another question. The scenario can be considered in 2 settings: emergency department and operating room.

Given the poor accuracy and interobserver agreement found in our study, along with the inaccuracy of caliper and ruler measurements, it seems decisions to perform tenorrhaphy based on reported percentages lacerated are unreliable. Our results showed that the ability to accurately assess partial tendon injuries does not improve with surgeon experience, as fellowship-trained hand surgeons were not statistically more accurate or consistent than residents. To this effect, one institution treats all its partial flexor tendon lacerations with wound inspection and irrigation in the emergency department, under digital block and after neurovascular injury has been excluded.8 If the patient is able to actively flex and extend the digit without triggering, then the wound is closed without closing the tendon sheath, a dorsal blocking splint is applied, and motion is begun early, 48 hours later, regardless of laceration severity.