Chronic anticoagulation is a common preexisting condition in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty (TJA). Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common underlying disorder requiring chronic anticoagulation, affects more than 3 million patients in the United States—a number that is projected to increase to 16 million by 2050.1,2 Other common indications for anticoagulation are deep vein thrombosis (DVT) treatment, presence of a prosthetic heart valve, and venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention after hip or knee arthroplasty. These patients face the additional risks of hemorrhage, persistent wound drainage, hematoma formation, transfusion requirements, periprosthetic joint infection, and longer hospital stay.1 Chronic anticoagulation traditionally has been managed with warfarin, which inhibits production of the vitamin K–dependent clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X. However, the new novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), which target individual factors in the clotting cascade, are gaining favor as chronic anticoagulant agents because of their ease of use and improved efficacy and safety. These agents include the factor IIA inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa) and the direct factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis).

Management of patients at risk for thromboembolism and bleeding issues, particularly within the context of elective, urgent, or emergent orthopedic surgeries, is an evolving area. Understanding the pharmacokinetics, conventional laboratory tests, dosing, and reversal methods for NOACs is important, especially because clinical data are limited and the treatment itself can cause clinically significant harm.

In this article, we review the medical literature on these medications, their mechanism of action, and their reversal agents, and outline a practical approach for managing patients during the perioperative period.

Dabigatran

In October 2010, dabigatran became the first NOAC approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention of arterial thromboembolic events in patients with nonvalvular AF, on the basis of the results of the RELY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy) trial. Dabigatran is an oral factor IIA (thrombin) inhibitor. From time of ingestion, dabigatran takes 1.25 to 3 hours to reach peak plasma concentration. It has a half-life of 12 to 14 hours, is excreted predominantly by the kidneys (80%), and is renally dosed. The usual dose is 150 mg 2 times daily if creatinine clearance (CrCl) is >30 mL/minute, or 75 mg 2 times daily if CrCl is 15 to 30 mL/minute.3 Dabigatran is not recommended for patients with CrCl <15 mL/minute.

Dabigatran affects prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), ecarin clotting time, and thrombin time, with the latter 2 providing the most accurate means of monitoring appropriate drug levels.3,4 Of the tests commonly used to assess coagulation hemostasis in hospitals, normalization of thrombin time and aPTT provide the most accurate results (Table 1). The pharmacokinetics of dabigatran mandate consideration of dose, time of ingestion relative to time of blood sampling, and renal function in the assessment of coagulation hemostasis.

For elective surgeries, the periprocedure recommendation for patients being treated with dabigatran is to discontinue the medication 3 to 4 days before an operation if CrCl is ≥50 mL/minute, or 4 to 5 days beforehand if CrCl is <50 mL/minute.3 There is no antidote for dabigatran. In an in vitro model, activated charcoal reduced 99.9% of dabigatran absorption after recent ingestion.3 According to case reports, acute hemodialysis successfully removed 60% of the medication after 6 hours.5 In patients with end-stage renal disease, hemodialysis removed up to 68% of active dabigatran after 4 hours.3

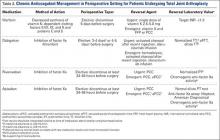

Pernod and colleagues6 proposed that urgent surgeries can proceed if the concentration of dabigatran is ≤30 ng/mL—equivalent to normal aPTT. Their dictum was extrapolated from the data of patients who underwent elective surgeries while being treated with dabigatran, as recorded during the RELY trial. According to Pernod and colleagues,6 if aPTT is increased (probable drug level, ≥30 ng/mL), surgery should be postponed for up to 12 hours, with aPTT checked again and the process repeated if the concentration of dabigatran is still elevated and surgery can continue to be delayed. In patients who require urgent surgical interventions, we previously utilized nanofiltered activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC; Feiba NF) 30 to 50 IU/kg over prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC; Kcentra or Bebulin) 25 to 50 IU/kg, as supported by in vitro and animal model studies and anecdotal case reports. However, neither aPCC nor PCC fully corrects the abnormalities evident on hemostasis tests.3,6 In October 2015, the FDA approved Idarucizumab (Praxbind), an injectable monoclonal antibody fragment that binds to dabigatran, as a reversing agent for use in urgent/emergent settings. Recommendation is to administer two 50-ml bolus infusions, each containing 2.5 g of idarucizumab, no more than 15 minutes apart.7 Additionally, hemodialysis could be discussed before surgery, with the understanding that it will take a long time to reach the threshold of 30 ng/mL in these patients (Table 2).