American football has the highest injury rate of any team sport in the United States at the high school, collegiate, and professional levels.1-3 Muscle strains and contusions constitute a large proportion of football injuries. For example, at the high school level, muscle strains comprise 12% to 24% of all injuries;2 at the collegiate level, they account for approximately 20% of all practice injuries, with nearly half of all strains occurring within the thigh.1,4 Among a single National Football League (NFL) team, Feeley and colleagues5 reported that muscle strains accounted for 46% of practice and 22% of preseason game injuries. The hamstrings, followed by the quadriceps, are the most commonly strained muscle groups among both professional and amateur athletes,5,6 with hamstring and quadriceps injuries making up approximately 13% of all injuries among NFL players.7 Given the relatively large surface area and muscle volume of the anterior and posterior thigh, as well as the activities and maneuvers necessitated by the various football positions, it is not surprising that the thigh is frequently involved in football-related injuries.

The purpose of this review is to describe the clinical manifestations of thigh-related soft-tissue injuries seen in football players. Two of these conditions—muscle strains and contusions—are relatively common, while a third condition—the Morel-Lavallée lesion—is a rare, yet relevant injury that warrants discussion.

Quadriceps Contusion

Pathophysiology

Contusion to the quadriceps muscle is a common injury in contact sports generally resulting from a direct blow from a helmet, knee, or shoulder.8 Bleeding within the musculature causes swelling, pain, stiffness, and limitation of quadriceps excursion, ultimately resulting in loss of knee flexion and an inability to run or squat. The injury is typically confined to a single quadriceps muscle.8 The use of thigh padding, though helpful, does not completely eliminate the risk of this injury.

History and Physical Examination

Immediately after injury, the athlete may complain only of thigh pain. However, swelling, pain, and diminished range of knee motion may develop within the first 24 hours depending on the severity of injury and how quickly treatment is instituted.8 Jackson and Feagin9 developed an injury grading system for quadriceps contusions based on the limitation of knee flexion observed (Table 1).

Fortunately, the majority of contusions in these athletes are of a mild to moderate severity.9,10Imaging

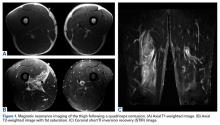

A quadriceps contusion is a clinical diagnosis based on a typical history and physical examination; therefore, advanced imaging usually does not need to be obtained except to gauge the severity of injury, to rule out concurrent injuries (ie, tendon rupture), and to identify the presence of a hematoma that may necessitate aspiration. Plain radiographs are typically unremarkable in the acute setting. Appearance on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) varies by injury severity, with increased signal throughout the affected muscle belly and a diffuse, feathery appearance centered at the point of impact on short TI inversion recovery (STIR) and T2-weighted images reflecting edema and possibly hematoma (Figures 1A-1C).8,11

Resolution of these MRI findings may lag behind functional recovery.8 Therefore, the athlete is often able to return to competition once he has recovered full lower extremity motion and function despite the persistence of abnormal findings on MRI.Treatment

Treatment of a quadriceps contusion is nonoperative and consists of a 3-phase recovery.10 The first phase lasts approximately 2 days and consists of rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) to limit hemorrhage. The knee should be rested in a flexed position to maintain quadriceps muscle fiber length in order to promote muscle compression and limit knee stiffness. For severe contusions in which there is a question of an acute thigh compartment syndrome, compression should be avoided with appropriate treatment based on typical symptoms and intra-compartmental pressure measurement.12 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be administered to diminish pain as well as the risk of myositis ossificans. While there is no data on the efficacy of NSAIDs in preventing myositis ossificans following quadriceps contusions, both COX-2 selective (ie, celecoxib) and nonselective (ie, naproxen, indomethacin) COX inhibitors have been demonstrated to significantly reduce the incidence of heterotopic ossification following hip surgery—a condition occurring from a similar pathophysiologic process as myositis ossificans.13-17 However, this class of drugs should not be given any sooner than 48 to 72 hours after injury to decrease further bleeding risk, given its inhibitory effect on platelet function.18 Narcotic pain medications are rarely required.

The second phase focuses on restoring active and passive knee and hip flexion and begins when permitted by pain.8 Icing, pain control, and physical therapy modalities are also continued in order to reduce pain and swelling as knee motion is progressed. The third phase begins once full range of knee and hip motion is restored and consists of quadriceps strengthening and functional rehabilitation of the lower extremity.8,19 Return to athletic activities and eventually competition should take place when a full, painless range of motion is restored and strength returns to baseline. Isokinetic strength testing may be utilized to more accurately assess strength and endurance. Noncontact, position-specific drills are incorporated as clinical improvement allows. A full recovery should be expected within 4 weeks of injury, with faster resolution and return to play seen in less severe contusions depending on the athlete’s position.8 Continued quadriceps stretching is recommended to prevent recurrence once the athlete returns to play. A protective hard shell may also be utilized both during rehabilitation as well as once the athlete returns to play in order to protect the thigh from reinjury, which may increase the risk of myositis ossificans.8