Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The majority of hamstring strains are sustained during noncontact activities, with most athletes citing sprinting as the activity at the time of injury.3 Approximately 93% of injuries occur during noncontact activities among defensive backs and wide receivers.3 Hamstring strains are the second-most common injury among NFL players, comprising approximately 9% of all injuries,5,7 with 16% to 31% of these injuries associated with recurrence.3,5,35,46 Using the NFL’s Injury Surveillance System, Elliott and colleagues3 reported 1716 hamstring strains over a 10-year period (1989-1998). Fifty-one percent of hamstring strains occurred during the 7-week preseason, with a greater than 4-fold increased injury rate noted during the preseason compared to the 16-week regular season. An increased incidence in the preseason is partially attributable to relative deconditioning over the offseason. Defensive backs, wide receivers, and special teams players accounted for the majority of injured players, suggesting that speed position players and those who must “backpedal” (run backwards) are at an increased risk for injury.

Several risk factors for hamstring strain have been described, including prior injury, older age, quadriceps-hamstring strength imbalances, limited hip and knee flexibility, and fatigue.39,42,47 Inadequate rehabilitation and premature return to competition are also likely important factors predisposing to recurrent injury.39,48

History and Physical Examination

The majority of hamstring strains occur in the acute setting when the player experiences the sudden onset of pain in the posterior thigh during strenuous exercise, most commonly while sprinting.39 The injury typically occurs in the early or late stage of practice or competition due, in part, to inadequate warm-up or fatigue. The athlete may describe an audible pop and an inability to continue play, depending on injury severity.

Physical examination may demonstrate palpable induration and tenderness immediately or shortly after injury. In the setting of severe strains, there can be significant thigh swelling and ecchymosis, and in complete ruptures, a palpable defect.39 The affected muscle should be palpated along its entire length, and is best performed prone with the knee flexed to 90° as well as with the knee partially extended to place it under mild tension. Injury severity can be assessed by determining the restriction of passive knee extension while the athlete is lying supine with the hip flexed to 90°. The severity of hamstring strains varies from minor damage of a few myofibers without loss of structural integrity to complete muscle rupture.

Hamstring strains are classified into 3 groups based on the amount of myotendinous disruption (Table 3).49Imaging

Similar to other muscle strains, hamstring strains are a clinical diagnosis and generally do not necessitate advanced imaging studies except to assess the degree of damage (ie, partial vs complete rupture) and to rule out other injuries, especially if the athlete fails to respond to treatment. Plain radiographs in acute cases are usually unremarkable. However, more severe injuries may go on to develop myositis ossificans similar to quadriceps soft tissue injuries (Figure 5).

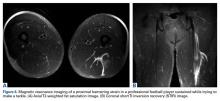

The MRI appearance of hamstring strains shows increased signal within and surrounding the affected muscle belly on T2-weighted imaging as well as the degree of muscle fiber disruption (Figures 6A, 6B). MRI can also be beneficial to confirm the diagnosis of myositis ossificans in chronic cases with a palpable mass.Treatment

Most hamstring strains respond to conservative treatment, with operative intervention rarely indicated except for proximal or distal tendon avulsions.39 Like other muscle strains, initial management consists of RICE. COX-2-selective NSAIDs are preferred initially following injury. During a brief period of immobilization, the leg should be extended as much as tolerated to maximize muscle length, limit hematoma formation, and reduce the risk of contracture.39 Controlled mobilization should begin as soon as tolerated by the athlete.39 Isometric exercises and a stretching program should be started early in the rehabilitation period, with isotonic exercises added as motion and pain improve. Active stretching should be initiated and progressed to passive, static stretching as guided by pain.

The late phase of rehabilitation and long-term conditioning protocols should incorporate eccentric training once the athlete is pain-free, performing isotonic and isokinetic exercises. Eccentric exercises best strengthen the hamstrings at their most susceptible point, prepares the athlete for functional activities, and minimizes the risk of reinjury,3,50,51 Elliot and colleagues3 reported an order of magnitude decrease in hamstring injuries in high-risk athletes with identifiable hamstring muscle weakness after implementing an eccentric strengthening program and progressive sprint training. Similarly, in a large cohort of elite soccer players, correction of strength deficits in players with prior hamstring injuries led to similar rates of injury compared to athletes without strength deficits or prior injury.52 Those athletes with persistent weakness who did not undergo rehabilitation had significantly higher rates of reinjury.

Various injections containing local anesthetics, corticosteroids, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and other substances have been administered to football players following acute muscle strains in an effort to alleviate pain and safely return the athlete to competition. Some practitioners have been reluctant to administer injections (especially those containing corticosteroids) due to a potentially increased risk of tendinopathy or rupture.31 Drakos and colleagues53 reported their outcomes following muscle and ligament strains treated with combined corticosteroid and local anesthetic injections on one NFL team. While quadriceps and hamstring strains were associated with the most missed games among all muscle strains, these injections resulted in no adverse events or progression of injury severity. Similarly, Levine and colleagues 51 administered intramuscular corticosteroid injections to 58 NFL players with high-grade hamstring injuries that had a palpable defect within the muscle belly. They reported no complications or strength deficits at final examination. In a case-control study, Rettig and colleagues46 administered PRP injections under ultrasound guidance in 5 NFL players with hamstring injuries. Compared to players treated with a focused rehabilitation program only, there were no significant differences in recovery or return to play.

The decision to return to play should be based on a clinical assessment considering pain, strength, motion, and flexibility. Player position should also be considered. Return-to-play guidelines describing the appropriate progression through rehabilitation and return to sport have been described and can be used as a template for the rehabilitation of football players.54 It should be noted that primary hamstring strains are associated with decreased athletic performance and an increased risk of more severe reinjury after return to sport.55,56