End-stage osteoarthritis of the hip is a debilitating disease that is reliably treated with total hip arthroplasty (THA).1 Up to 35% of patients who undergo THA eventually require contralateral THA.2,3 In patients who present with advanced bilateral disease and undergo unilateral THA, the risk of ultimately requiring a contralateral procedure is as high as 97%.3-6 In patients with bilateral hip disease, function is not fully optimized until both hips have been replaced, particularly in the setting of fixed flexion contractures.7-9 Naturally, there has been some interest in simultaneous bilateral THAs for select patients.

The potential benefits of bilateral THAs over staged procedures include faster overall rehabilitation, exposure to a single anesthetic, reduced hospital length of stay (LOS), and cost savings.10-12 However, opinion on recommending bilateral THAs is mixed. Although bilateral procedures historically have been fraught with perioperative complications,13,14 advances in surgical and anesthetic techniques have led to improved outcomes.15 Whether surgical approach is a factor in these outcomes is unclear.

The popularity of the direct anterior (DA) approach for THA has increased in recent years.16 Although the relative advantages of various approaches remain in debate, one potential benefit of the DA approach is supine positioning, which allows simultaneous bilateral THAs to be performed without the need for repositioning before proceeding with the contralateral side. However, simultaneous bilateral THAs performed through the DA approach and those performed through other surgical approaches are lacking in comparative outcomes data.17In this study, we evaluated operative times, transfusion requirements, hospital discharge data, and 90-day complication rates in patients who had simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach.

Methods

Study Design

This single-center study was conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. After obtaining approval from our Institutional Review Board, we performed a retrospective cohort analysis. We used our institution’s total joint registry to identify all patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach. The first bilateral THAs to use the DA approach at our institution were performed in 2012. To ensure that the DA and posterior groups’ perioperative management would be similar, we included only cases performed between 2012 and 2014.

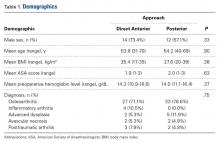

There were 19 patients in the DA group and 21 in the posterior group. The groups were similar in mean age (54 vs 54 years; P = .90), sex (73% vs 57% males; P = .33), body mass index (BMI; 25 vs 28 kg/m2; P = .38), preoperative hemoglobin level (14.3 vs 14.0 g/dL; P = .37), preoperative diagnosis (71.1% vs 78.6% degenerative joint disease; P = .75), and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score (1.9 vs 2.0; P = .63) (Table 1).

All patients had clinical follow-up of at least 90 days.Patient Care

All cases were performed by 1 of 3 dedicated arthroplasty surgeons (Dr. Taunton, Dr. Sierra, Dr. Trousdale). Dr. Taunton exclusively uses the DA approach, and Dr. Sierra and Dr. Trousdale exclusively use the posterior approach. Patients in both groups received preoperative medical clearance and attended the same preoperative education class.

Patients in the DA group were positioned supine on an orthopedic table that allows hyperextension and adduction of the operative leg. Both hips were prepared and draped simultaneously. The most symptomatic hip was operated on first, with a sterile drape covering the contralateral hip. Between hips, fluoroscopy was moved to the other side of the operative suite, but no changes in positioning or preparation were necessary. A deep drain was placed on each side, and then was removed the morning of postoperative day 1. The same set of instruments was used on both sides.

Patients in the posterior group were positioned lateral on a regular operative table with hip rests. The most symptomatic hip was operated on first. After wound closure and dressing application, the patient was flipped to allow access to the contralateral hip and was prepared and draped again. The same instruments were used on each side. Drains were not used.

All patients received the same comprehensive multimodal pain management, which combined general and epidural anesthesia (remaining in place until postoperative day 2) and included an oral pain regimen of scheduled acetaminophen and as-needed tramadol and oxycodone. In all cases, intraoperative blood salvage and intravenous tranexamic acid (1 g at time of incision on first hip, 1 g at wound closure on second hip) were used. Preoperative autologous blood donation was not used. For deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, patients were treated with bilateral sequential compression devices while hospitalized, but chemoprophylaxis was different between groups. Patients in the DA group received prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin for 10 days, followed by twice-daily aspirin (325 mg) for 4 weeks. Patients in the posterior group received warfarin (goal international normalized ratio, 1.7-2.2) for 3 weeks, followed by twice-daily aspirin (325 mg) for 3 weeks. The decision to transfuse allogenic red blood cells was made by the treating surgeon, based on standardized hospital protocols, wherein patients are transfused for hemoglobin levels under 7.0 g/dL, or for hemoglobin levels less than 8.0 g/dL in the presence of persistent symptoms. All patients received care on an orthopedic specialty floor and were assisted by the same physical therapists. Discharge disposition was coordinated with the same group of social workers.

Two to 3 months after surgery, patients returned for routine examination and radiographs. All patients were followed up for at least 90 days.