5. Hip Abductor Weakness

The step-down test is easily performed in the office by having the patient stand on a short stool or stair and then slowly step down with the opposite limb to just touch the heel and slowly arise again. A positive test is indicated by the Trendelenburg sign, with the pelvis dropping down and away from the symptomatic supporting limb, the flexing knee collapsing into valgus, and the patient tending to wobble and lack stability (Figure 4).16

With mild hip abductor weakness, these changes can be subtle, but they may become more severe with increasing weakness. Khayambashi and colleagues17 found that hip abductor weakness can be a major cause of patellofemoral pain.6. Patella Alta

Patella alta not only allows the patella to escape the confines of the trochlea earlier during active knee extension increasing the risk of patellar dislocation, but also decreases the contact footprint with the trochlea, increasing the patellofemoral joint reaction force and potentially causing patellofemoral pain and even secondary chondrosis. The simplest way to assess patellar height is with a lateral radiograph of the knee. The 3 popular methods (Insall-Salvati, Caton-Deschamps, Blackburn-Peel) all put the normal patellar height ratio at approximately 1:1, ± 20%. Berg and colleagues18 compared radiologic techniques for measuring patellar height ratio and found that Blackburn-Peel was the most accurate, reliable, and reproducible method.

7. Trochlear Dysplasia

Trochlear dysplasia, most simply a flattening of the TG, is perhaps the most important factor effecting normal patellofemoral function. However, it remains the most difficult to correctly address surgically. Senavongse and Amis19 conducted a cadaveric study demonstrating the prime importance of the TG. They found patellar stability was reduced 30% by releasing the VMO, 49% by cutting the MPFL in full knee extension, and 70% by flattening the trochlea. The most common, successful operations for correcting patellar instability depend on changing other factors that guide patellar excursion to compensate for this trochlear flattening.

The simplest way to assess trochlear dysplasia is to measure the sulcus angle on an accurate axial view radiograph of the knee at 45° flexion (Merchant view).20 Dejour and colleagues21 popularized a technique of assessing and classifying trochlear dysplasia from a true lateral radiograph of the knee, which has the advantage of showing the trochlear at its proximal extent. Davies and colleagues22 evaluated the Dejour technique, along with patellar tilt, patellar height, and sulcus angle, to identify a rapid and reproducible radiologic feature that would indicate the need for further analysis by other imaging studies (eg, CT, MRI). They found that, if the sulcus angle was normal, analysis of other radiologic features was unlikely to reveal additional useful information. They also showed a correlation of increasing sulcus angle and severity of those other dysplasia features. Merchant and colleagues20 found a mean normal sulcus angle of 138º (SD, 6º; range, 126º-150º), and Aglietti and colleagues23 confirmed those findings with nearly identical values (mean, 137º; SD, 6º; range, 116º-151º).

Diagnosis and Initial Treatment Plan

Patellofemoral disorders generally are divided into patellofemoral pain and instability, but these 2 diagnostic categories are too broad to be useful. Patellofemoral pain is a symptom. Patellofemoral pain syndrome should never be used as a diagnosis because there is no accepted definition for the cluster of findings that customarily defines a syndrome. At initial evaluation, after the easily diagnosed causes of anterior knee pain (eg, prepatellar bursitis, TT apophysitis, patellar and quadriceps tendinitis) have been ruled out, the clinician should consider types of patellofemoral dysplasia for a presumptive diagnosis, which will then lead to a logical treatment program for each identified disorder. With a presumptive diagnosis established, almost all patients suffering from chronic anterior knee pain without history of injury are treated initially with rest, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to restore joint homeostasis.3

Lateral Patellar Compression Syndrome

In 1975, Ficat and colleagues24 described features of what they called syndrome d’hyperpression externe de la rotule. Two years later, Ficat and Hungerford25 defined the syndrome as one “in which the patella is well centered in the trochlear sulcus and stable, but in which there is a functional lateralization onto a physiologically and often anatomically predominant lateral facet.” Using the tools we have described here, the clinician usually finds the cause(s) of this “functional lateralization.” Four abnormalities—VMO deficiency, LR tightness, increased standardized Q angle, and hip abductor weakness—can cause functional lateralization either alone when severe or in combination when mild or moderate.

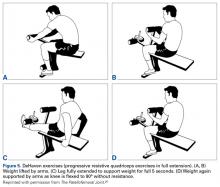

For a presumptive diagnosis of LPCS, initial treatment is nonoperative, and successful in about 90% of patients. It should be obvious that most patients with chronic anterior knee pain have quadriceps atrophy. Physical therapy should be specifically focused on quadriceps strengthening, with absolutely no stress placed on the patellofemoral joint in flexion initially, and on hip abductor strengthening. Progressive resistive isometric quadriceps exercises can be performed with a weight-bench technique (Figures 5A-5D).26

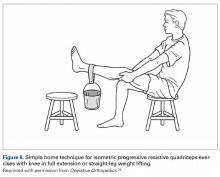

These isometric progressive resistive quadriceps (DeHaven27) exercises can also be performed with a simple straight-leg weight-lifting program at home (Figure 6).28 The advantage of isometric quadriceps strengthening is that the knee is in full extension, the patella lies above the trochlea, and there is no patellofemoral joint movement or compression. A patient of average stature can gradually increase quadriceps strength to resist or lift about 20 lb. Progressive hip abductor strengthening can be done in physical therapy or at home using side-lying abductor exercises with ankle weights. DeHaven27 exercises should be painless when done correctly, but contraindicated in patients with patellar tendinitis, quadriceps tendinitis, TT apophysitis (Osgood-Schlatter’s), and anterior fat pad (Hoffa’s) syndrome. When appropriate, certain adjunctive modalities for reducing functional lateralization should be tried. Use of McConnell taping and patellar bracing to resist this lateralization can be very helpful. If symptoms persist despite the 20-lb quadriceps goal being achieved and adequate hip abductor strength being demonstrated in a normal step-down test, conservative management has failed. Review and reassessment of the remaining abnormal physical factors (tight LR, increased Q angle) will lead to logical choices in surgical management.