Appropriate Rehabilitation in AKP

Appropriate rehabilitation addresses all identified strength and flexibility deficits in order to improve functional biomechanics and normalize altered body movement patterns during daily activities (eg, walking, squatting, stair climbing). Often, if part of the kinetic chain is weak or injured, the body engages in an activity by “working around” the injured body part. This change often results in faulty body mechanics or altered movement patterns. In AKP, these modified biomechanics can result in pain centered on the patella and associated soft-tissue structures. In developing ways to compensate for strength and ROM deficits, patients with AKP exacerbate their symptoms. In long-standing AKP, these compensatory strategies are most often unintentional and ingrained.

The main role of physical therapists is to identify any faulty movement patterns, dissect the underlying neuromuscular causes of these deficits, and build an individualized rehabilitation program. Physical therapy should be customized to the patient’s level of strength and fitness and whenever possible should be made challenging (and fun!) for the patient. The exercises should be increased in intensity and duration as the patient improves strength, endurance, and control in the activities. The patient’s response to each intervention will help guide exercise progression and define the need for further treatments.

Patients should be assessed for overuse patterns. Overuse can occur with repetitive exercise activity, such as running, or with repetitive work activity that involves lifting, squatting, or stair climbing. It is important to modify or reduce such activity to ensure that a patient with AKP remains within an envelope of pain-free function. Once the patient is functioning in this envelope, rehabilitation can be redirected to expand it, while improving strength, coordination, balance, and overall dynamic control of the core and lower limbs.

The purpose of any rehabilitation program is to build strength through the entire kinetic chain, focusing on hip and core strength initially, and then adding concentric and eccentric lower limb strength. Having a strong base from which to initiate lower limb movements makes correct lower limb form more likely to follow. Corrected muscle firing patterns allow for appropriate sequencing of the muscle activation needed for proper movements. Corrected muscle tendon lengths allow for optimal firing of the muscles controlling the lower limb, and for the flexibility needed for everyday ROM and biomechanics. Patients with AKP require re-education of movements that occur during daily functional activities, including gait. Once correct movement patterns are established in daily activities, it is important to address sporting or work-related activities. This is one important reason to ensure that physiotherapy visits are distributed over time and that patient-centered goals are addressed during each visit. In addition, during therapy, it is essential to reexamine body movement patterns to identify any relapse to prior dysfunction as the intensity or frequency of activity increases.

In AKP management, the dosage and duration of exercise prescriptions are challenging, and patience and perseverance are paramount. The initial goal of therapy is to increase strength and ROM to enable practice of correct motion in daily activities (eg, stair climbing, sitting, and walking). The physical therapist’s challenge is to teach correct motion within the envelope of function, as described by Dye.25 Pain is not gain, and all exercises must be performed without pain to avoid flaring symptoms. The patient and the therapist must collaborate to complete a pain free rehabilitation program, and must operate within that zone. Providing prescriptions with specific goals may be helpful. Example goals are, “Increase core and lower extremity strength to achieve squatting without medial collapse of knee,” “Hip and core strengthening and endurance,” “Equal quadriceps strength and girth,” and “Functional movement retraining.”

Assessing Adequacy of Rehabilitation in AKP

When a patient presents with a diagnosis of AKP, it can be difficult to establish whether a prior rehabilitation program was appropriate. The fact that a patient attended physiotherapy says nothing about the quality of the therapy provided. Neither does the number of sessions attended. To assess the quality of the rehabilitation and determine if there are any major deficits in neuromuscular function, the physician can perform a simple battery of screening tests (Figure 1).26

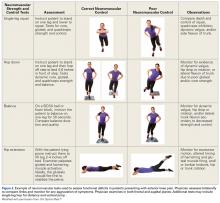

These tests may reveal gross strength deficits that equate to significant functional deficits. Alternatively, core and gluteal strength can be assessed by having the patient perform a pelvic bridge, as another test that is appropriate and easy in the physician clinical setting.More advanced tests can be used to better understand the neuromuscular function of the patient with AKP and tease out specific deficits. Figure 226 describes some of these tests and the typical compensatory motions seen in patients with altered movement patterns.

For example, observing a single- or double-leg squat in the frontal and sagittal planes can be useful in assessing the quality of prior rehabilitation and determining the need for further physical therapy. Observing for dynamic alignment provides a snapshot of the forces that the knee may be subjected to, with increased force and repetition, while participating in daily activities and sport. In the frontal plane, functional valgus with dynamic activities (eg, single- and double-leg squats) may result from weakness in the core and hip musculature. In the sagittal plane, increased anterior translation of the knee over the foot can indicate poor squat mechanics, lack of gluteal activation, or poor eccentric quadriceps control. Gripping with the toes and increased ankle dorsiflexion are often a sign of anterior muscle recruitment and therefore increased load through the anterior compartment of the knee. Lack of appropriate body movement patterns is often evident to both the physician and patient, and this feedback can provide the patient with incentive for further (more directed) rehabilitation.Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):82-86. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.