Take-Home Points

- Lateral patella dislocation is sufficiently treated with modern versions of patellofemoral surgery.

- Comprehensive assessment for underlying osseous pathology is paramount (torsional abnormalities of the femur or tibia, trochlea dysplasia, patella alta, etc).

- In such cases, isolated medial patellofemoral ligament reconstructions will fail. Instead, the underlying osseous abnormalities must be addressed during concomitant procedures (derotational osteotomy, tibial tubercle transfer, trochleoplasty, etc).

The incidence of patellar instability is high, particularly in young females. In principle, cases of patellar instability can be classified as traumatic (dislocation is caused by external, often direct forces) or nontraumatic (anatomy predisposes to instability).1-4

Because the vast majority of unstable patellae are unstable toward lateral and because instability is objective when the patella is fully dislocated, we use the term lateral patella dislocation (LPD) and refer to primary and recurrent LPD throughout this review.Anatomy Predisposing to Patella Dislocation

Most patients present with specific anatomical factors that predispose to patellar instability (isolated or combined).

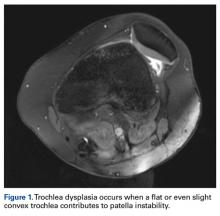

These can be grossly categorized as osteochondral factors and soft-tissue factors.Of the osteochondral factors, dysplasia of the femoral trochlea (trochlea groove [TG]) is most important. In healthy patients, the concave trochlea stabilizes the patella in knee flexion angles above 20°. In particular, the lateral facet of the trochlea plays a key role in withstanding the lateralizing quadriceps vector. The dysplastic trochlea, which has a flat or even a convex surface, destabilizes the patella (Figure 1). Moreover, patella alta is a pivotal factor in the development of LPD.

A high-riding patella engages the femoral trochlea during higher degrees of knee flexion, making the patella very susceptible to dislocations when the knee is almost in extension.5,6 In addition, high femoral anteversion (increased femoral internal torsion) has been reported as contributing to the development of LPD. Internal torsion of the distal femur brings the TG more medial and therefore provokes a lateral shift of the patella relative to the femur (Figure 2).7-11 Valgus knee alignment is also common in patients with LPD. First, tibiofemoral valgus brings the tibial tuberosity (TT) more toward lateral and therefore increases the pull on the patella toward lateral. Second, when the deformity is at the distal femur, there is often a hypoplastic lateral condyle, which can contribute to LPD in knee flexion angles above 45°. Deformities in the frontal plane (valgus) and the transverse plane (increased internal torsion of the femur, increased external torsion of the proximal tibia) commonly increase the TT-TG distance. TT-TG distance is a radiographic parameter, taken from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography, that summarizes important aspects of patellofemoral alignment and gives an impression of the amount of lateralizing force of the extensor apparatus (discussed later) (Figure 3).The anteromedial soft tissue of the knee (retinaculum) has 3 layers, the second of which contains the

medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL).12,13 On the femoral side, the MPFL originates in direct proximity to the medial epicondyle and the adductor tubercle. The MPFL broadens toward the patella (V-shaped) and inserts at the superomedial border of the patella and the adjacent aspects of the quadriceps tendon.14-17 It has been found to provide an important restraint against LPD.18-20 In primary LPD, the MPFL has been found ruptured or severely damaged in more than 90% of cases, most often near the femoral insertion.18,21-23 In patients with an elongated, insufficient MPFL, the patella may dislocate laterally without rupturing the MPFL. Another soft-tissue structure that contributes to patellar stabilization is the lateral retinaculum, which provides a restraint toward posterior rather than lateral (Figure 4). Cutting the lateral retinaculum would further decrease patellar stability in most cases.18,24-26We strongly recommend that physicians assess for all these osteochondral and soft-tissue abnormalities in patients with LPD.Diagnostics

Physical Examination

It is recommended that the physician starts the examination by assessing the walking and standing patient while focusing on torsional malalignment of the lower extremities (increased antetorsion of the femur, increased external torsion of the tibia), which is often indicated by squinting patellae.8,27,28

In addition, valgus knee alignment, increased foot pronation, and weakness of hip external rotators and hip abductors (Trendelenburg sign) are regularly observed in patients with LPD.29 Beyond walking and standing, additional functional tests (eg, single-leg squat, single-leg balancing, step-down test) were suggested as reliably provoking these pathologic kinematics.30 It is also suggested that the patient be examined sitting with lower legs hanging. In many cases, patients who are asked to actively extend the leg with LPD present a so-called J sign, which means the patella moves laterally close to terminal knee extension (Figure 5). Examination continues with the patient supine. The physician uses the patella glide test to determine how far the patella can be translated toward lateral and medial. Grade 1 indicates the patella can be translated one-fourth of its width, and grade 4 indicates it can be translated its full width31 (Figure 6). The apprehension test is positive in the majority of patients with LPD and is performed in 30° knee flexion with relaxed quadriceps. The physician gently pushes the patella toward lateral. Avoidance or protective quadriceps contraction indicates a positive test.32,33 It is recommended that the physician forgo the Zohlen test (low specificity) and instead use the extension test, in which the patient tries to extend the leg against physician resistance at 0°, 30°, 60°, and 90°. The extension test provokes pain in the case of significant degeneration at the respective joint areas under contact pressure. The patient should also be examined in the prone position in order to assess for torsional deformities. With knees in 90° flexion, maximum external rotation and maximum internal rotation of the hips are determined on both sides at the same time (Figures 7A, 7B). Patients with significant internal rotation (>60°) and poor external rotation are suspected as having increased femoral antetorsion.