The Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS), described by Cowan and colleagues,11 was used to evaluate the methodologic quality of each study. The MCMS is a 15-item instrument that has been used to assess both randomized and nonrandomized trials.12,13 It has a scaled score ranging from 0 to 100 (85-100, excellent; 70-84, good; 55-69, fair; <55, poor). Study quality was not factored into the data synthesis analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as weighted means and standard deviations. A mean was calculated for each study reporting on a respective data point and was then weighed according to the study sample size. The result was that the nonweighted means from studies with smaller samples did not carry as much weight as those from studies with larger samples. Student t tests and 2-way analysis of variance were used to compare the ST and LTO groups and assess differences over time (SPSS Version 18; IBM). An α of 0.05 was set as statistically significant.

Results

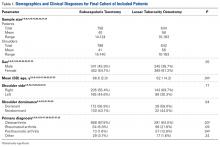

Twenty studies (1420 shoulders, 1392 patients) were included in the final dataset (Figure).2,6,8,14-30 Table 1 lists the demographic characteristics of included patients. Of the 20 studies, 12 reported level IV evidence, 6 reported level III, 1 reported level II, and 1 reported level I. Mean (SD) MCMS was 51.9 (11.2) for ST studies and 46.3 (8.1) for LTO studies.

The youngest patients in the ST and LTO groups were 22 years and 19 years of age, respectively.

The oldest patient in each group was 92 years of age. On average, the ST study populations (mean age, 66.6 years; SD, 2.0 years) were older (P = .04) than the LTO populations (mean age, 62.1 years; SD, 4.2 years). The ST group had a higher percentage of patients with osteoarthritis (P = .03) and fewer patients with posttraumatic arthritis (P = .04). There were no significant differences in sex, shoulder side, or shoulder dominance between the 2 groups.Table 2 lists the details regarding the surgical components. For glenoid components, the ST and LTO groups’ fixation types and material used were not significantly different.

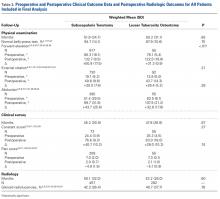

There was a significant (P < .01) difference in use of pegged (vs keeled) glenoid components (all LTO components were pegged). There was also a significant (P = .04) difference in use of cement for humeral components (the ST group had a larger percentage of cemented humeral components). There were no other significant differences in components between the groups. When subgroup analysis was applied to keeled glenoid components and uncemented humeral components in the ST study populations, there were no significant changes in the radiographic or clinical trends.Table 3 lists the clinical and radiographic outcomes most consistently reported in the literature. Physical examination data were reported in 18 ST populations8,14-16,21-30 and 11 LTO populations.2,6,14-20

Mean (SD) forward elevation improvements were significantly (P < .01) larger for the ST group, +50.9° (17.5°), than for the LTO group, +31.3° (0.9°). There were no significant differences in preoperative/postoperative shoulder external rotation or abduction. In a common method of testing internal rotation, the patient is asked to internally rotate the surgical arm as high as possible behind the back. Internal rotation improved from L4–S1 (before surgery) to T5–T12 (after surgery) in the ST group8,16,24,26,28,29 and from S1 to T7–T12 in the LTO group.16,31 There were isolated improvements in other subscapularis-specific tests, such as belly-press resistance (lb),14 belly-press force (N),15 bear hug resistance (lb),14,23 liftoff,2,8,16 and ability to tuck in one’s shirt,2,16,23 but data were insufficient for comparisons between the 2 groups.Constant scores were reported in 4 ST studies14,22,24,27 and 3 LTO studies14,17,18 (Table 3). There was no significant difference (P = .37) in post-TSA Constant score improvement between the 2 groups. In the one study that performed direct comparisons, PSS improved on average from 29 to 81 in the ST group and from 29 to 92 in the LTO group.15 Several ST studies reported improved scores on various indices: WOOS (Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder), ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons), SST (Simple Shoulder Test), DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), SF-12 (Short Form 12-Item Health Survey), MACTAR (McMaster Toronto Arthritis Patient Preference Disability Questionnaire), and Neer shoulder impingement test.8,14,15,21,23-25,27-30 However, these outcomes were not reported in LTO cohorts for comparison. Similarly, 2 LTO cohorts reported improvements in SSV (subjective shoulder value) scores, but this measure was not used in the ST cohorts.6,17 Five ST studies recorded patients’ subjective satisfaction: 58% of patients indicated an excellent outcome, 35% a satisfactory outcome, and 7% a less than satisfactory outcome.21,23,25,26,29 Only 1 LTO study reported patient satisfaction: 69% excellent, 31% satisfactory, 0% dissatisfied.17

Complications were reported in 16 ST studies8,15,21-30 and 6 LTO studies.15,17-19 There were 117 complications (17.8%) and 58 revisions (10.0%) in the ST group and 52 complications (17.2%) and 49 revisions (16.2%) in the LTO group. In the ST group, aseptic loosening (6.2%) was the most common complication, followed by subscapularis tear or attenuation (5.2%), dislocation (2.1%), and deep infection (0.5%). In the LTO group, aseptic loosening was again the most common (9.0%), followed by dislocation (4.0%), subscapularis tear or attenuation (2.2%), and deep infection (0.7%). There were no significant differences in the incidence of individual complications between groups. The difference in revision rates was not statistically significant (P = .31).

Radiolucency data were reported in 12 ST studies19,21-26,28,30 and 2 LTO studies.17,18 There were no discussions of humeral component radiolucencies in the LTO studies. At final follow-up, radiolucencies of the glenoid component were detected in 42.3% of patients in the ST group and 40.7% of patients in the LTO group (P = .76).