Take-Home Points

- ICA dissections may occur from direct or indirect trauma.

- Symptoms can be mild, including a persistent headache.

- High clinical suspicion is required for diagnosis when symptoms are mild.

- Neuroimaging is required for definitive diagnosis.

- Conservative management with serial imaging can yield successful outcomes.

Cervical artery dissection (CAD) is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening condition that accounts for a high proportion of ischemic strokes in patients under the age of 45 years.1-4 The extracranial internal carotid arteries (ICAs) and vertebral arteries are most commonly involved; dissections can occur after either direct trauma to the neck, or indirect trauma resulting in acute hyperextension or hyperflexion.4-7 ICA dissection can be difficult to diagnose because of the varying symptomatology. Clinical presentation depends on stenosis location, degree of luminal narrowing, and presence or absence of ischemic stroke. Neurologic symptoms may be delayed, and misdiagnosis of an isolated soft-tissue contusion, whiplash, can be made in the setting of indirect cervical trauma.

Although this entity is well described in the literature,2,3,5,8 there are few reported cases of injuries sustained during high-intensity athletic competition. In this case report, we describe the symptoms, physical examination findings, diagnostic imaging results, and treatment of a young male athlete who presented with delayed-onset symptoms of ICA dissection resulting from indirect cervical trauma sustained during an ice hockey game. We discuss the importance of a high level of clinical suspicion in the diagnosis of neck injuries sustained during athletic competition, as well as the need for early vascular imaging for diagnosis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

The patient was a right-handed 32-year-old professional hockey goaltender. Four days before diagnosis, his goaltending mask and attached neck-protector were inadvertently lifted by another player’s stick just as a puck traveling at high speed struck him in the neck, to the right of the larynx, causing acute neck hyperextension. He immediately experienced discomfort and fell to the ice, saying he was “dizzy and light-headed.” Play was stopped, and medical personnel attended to him. His symptoms resolved, and he resumed play without any notable deficits. The next day, he noted discomfort at the impact site, but no additional symptoms, and received a presumptive diagnosis of cervical soft-tissue contusion. Continuing to participate in hockey that day, he did not develop any symptoms other than superficial cervical discomfort. However, the next morning, he presented complaining of severe right frontotemporal headache, which had persisted overnight. Orthopedic examination revealed palpable tenderness over the anterior cervical musculature, including the sternocleidomastoid and strap muscles. There was no appreciable hematoma in the contused area. Cervical range of motion was otherwise preserved. Cervical spine examination, including dermatomal and myotomal examination, was normal, as was cranial nerve examination. However, given the headache intensity and the recency of the injury, the potential for vascular or neurologic injury was considered. A neurology consultation was obtained, and arrangements were made for advanced cross-sectional imaging.

On further evaluation, the patient denied loss of consciousness, seizure, vomiting, amnesia, visual disturbance, language or cognitive impairment, balance or coordination difficulties, or any appreciable face or limb weakness. Review of systems was otherwise negative. Detailed neurologic examination did not reveal any cranial nerve deficits, and pupils were 3 mm, equal, and normally responsive to light and accommodation. Muscular tone and strength were symmetric and full in the upper and lower extremities. Gait, coordination, and response to vibration and temperature sensation were all preserved.

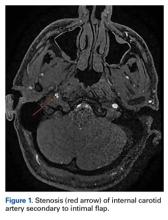

Magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck was normal, but magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the neck showed a 1-cm-long region of the ICA, before piercing the petrous bone, with evidence of dissection.

There was an associated intimal flap and about 50% luminal narrowing (Figure 1).Given the normal neurologic examination, and no evidence of brain infarction or other neurovascular complications, the acute ICA dissection was managed with antiplatelet therapy using aspirin (325 mg/d). In addition, the patient was advised to refrain from strenuous physical activity and to present to the hospital immediately if symptoms worsened or any neurologic impairment developed. Follow-up and repeat MRA were planned to monitor healing progression.

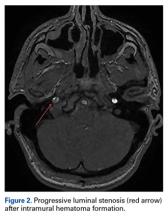

Two weeks after injury, the patient returned for follow-up. His headache and neck pain had resolved. Physical examination findings were unchanged, and there were no notable neurologic deficits. Repeat MRA findings were essentially unchanged, except for slightly increased luminal stenosis, exceeding 50% (Figure 2), attributable to intramural hematoma formation.

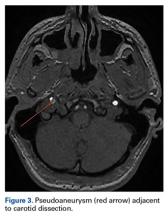

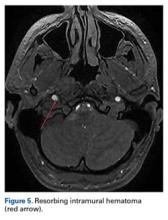

Adjacent to that was an associated pseudoaneurysm (Figure 3). Continued antiplatelet therapy and relative rest were advised. At 4 weeks, imaging showed increased luminal diameter, with the intramural hematoma resolving (Figure 4).At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no clinical symptoms and no recurrence of headaches.

Neurologic findings were again negative. MRA showed interval improvement with nearly complete resolution of the stenosis, with a small area of resorbing hematoma within the former pseudoaneurysm (Figure 5). Graduated return to activities was recommended, with cessation of activities and repeat assessment if symptoms returned. The patient successfully returned to his prior level of competition 8 weeks after injury. The Table summarizes the clinical events.