Classifying Bone Loss and Recognizing Its Effects

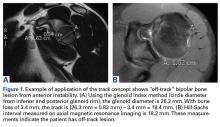

Burkhart and De Beer13 helped define the role and significance of bone loss in the setting of shoulder instability. They defined significant bone loss as an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion of the humerus in an abducted and externally rotated position or an “inverted pear” lesion of the glenoid. Overall analysis revealed recurrence in 4% of cases without significant bone loss and 65% of cases with significant bone loss. In a subanalysis of contact-sport athletes in the setting of bone loss, the failure rate increased to 89%, from 6.5%. Aiding in the quantitative assessment of glenoid bone loss, Itoi and colleagues17 showed that 21% glenoid bone loss resulted in instability that would not be corrected by a soft-tissue procedure alone. Bone loss of 20% to 25% has since been considered a “critical amount,” above which an arthroscopic Bankart has been questioned. More recently, several authors have shown that even less bone loss can have a significant effect on outcomes. Shaha and colleagues18 established that a subcritical level of bone loss (13.5%) on the anteroinferior glenoid resulted in clinical failure (as determined with the Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index) even in cases in which frank recurrence or subluxation was avoided. It is thought that, in recurrent instability, glenoid bone loss incident rate is as high as 90%, and the corresponding percentage of patients with Hill-Sachs lesions is almost 100%.19,20 Thus, it is increasingly understood that bone loss is a bipolar issue and that both sides must be considered in order to properly address shoulder instability in this setting. In 2007, Yamamoto and colleagues21 introduced the glenoid track, a method for predicting whether a Hill-Sachs lesion will engage. Di Giacomo and colleagues22 refined the track concept to quantitatively determine which lesions will engage in the setting of both glenoid and humeral bone loss. Metzger and colleagues,23 confirming the track concept arthroscopically, found that manipulation with anesthesia and arthroscopic visualization was well predicted by preoperative track measurements, and thus these measurements can be a good guide for surgical management (Figures 1A, 1B).

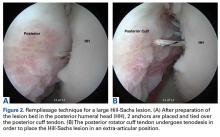

At Tripler Army Medical Center, Shaha and colleagues14 clinically validated the concept in a series of arthroscopic stabilization cases. They found that the recurrence rate was 8% for “on-track” patients’ and 75% for “off-track” patients treated with the same intervention. In addition, positive predictive value was 75% for the off-track measurement and 44% for the glenoid bone loss assessment alone. The authors recommended the preoperative off-track measurement over the glenoid bone loss assessment. In an analysis of computer modeling of 3-D CT of patients who underwent Bankart repair, Arciero and colleagues24 found that bipolar bone defects (glenoid bone loss combined with humeral head Hill-Sachs lesion) had an additive and combined negative effect on soft-tissue Bankart repair. In particular, soft-tissue Bankart repair could be compromised by a 2-mm glenoid defect combined with a medium-size Hill-Sachs lesion or, conversely, by a 4-mm glenoid defect combined with a small Hill-Sachs lesion (Figures 2A, 2B).Strategies for Addressing Bone Loss in Anterior Shoulder Instability

Several approaches for managing bone loss in shoulder instability have been described—the most common being coracoid transfer (Latarjet procedure). Waterman and colleagues25 recently studied the effects of coracoid transfer, distal tibial allograft, and iliac crest augmentation on anterior shoulder instability in US military patients treated between 2006 and 2012. Of 64 patients who underwent a bone block procedure, 16 (25%) had a complication during short-term follow-up. Complications included neurologic injury, pain, infection, hardware failure, and recurrent instability.

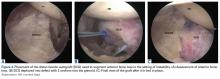

After undergoing 1 of the 3 procedures, 33% of patients had persistent pain, and 23% had recurrent instability. In an older, long-term study of Naval Academy midshipmen, patients who underwent a modified Bristow procedure between 1975 and 1979 demonstrated 70% good to excellent results at an average follow-up of 26.4 years.26 The recurrent instability rate was 15%, with 9% of the cohort dislocating again and 6% of the cohort experiencing recurrent subluxation. Direct bone grafting to the glenoid has also been described. Provencher and colleagues27 introduced use of distal tibial allograft in addressing bony deficiency, and clinical results were promising (Figures 3A-3C). Tokish and colleagues28 introduced use of distal clavicular autograft in addressing these deficiencies but did not report clinical outcomes (Figures 4A-4C).Conclusion

Traumatic anterior shoulder instability is a common pathology that continues to significantly challenge the readiness of the US military. Military surgeon-researchers have a long history of investigating approaches to the treatment of this pathology—applying good science to a large controlled population, using a single medical record, and demonstrating a commitment to return service members to the ready defense of the nation.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):184-189. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.