RADIOLOGICAL OUTCOME

No periprosthetic lucency or shift in component was observed at the last follow-up. There was no scapular notching. No resorption of the tuberosities, and no fractures of the acromion or the scapular spine were observed.

DISCUSSION

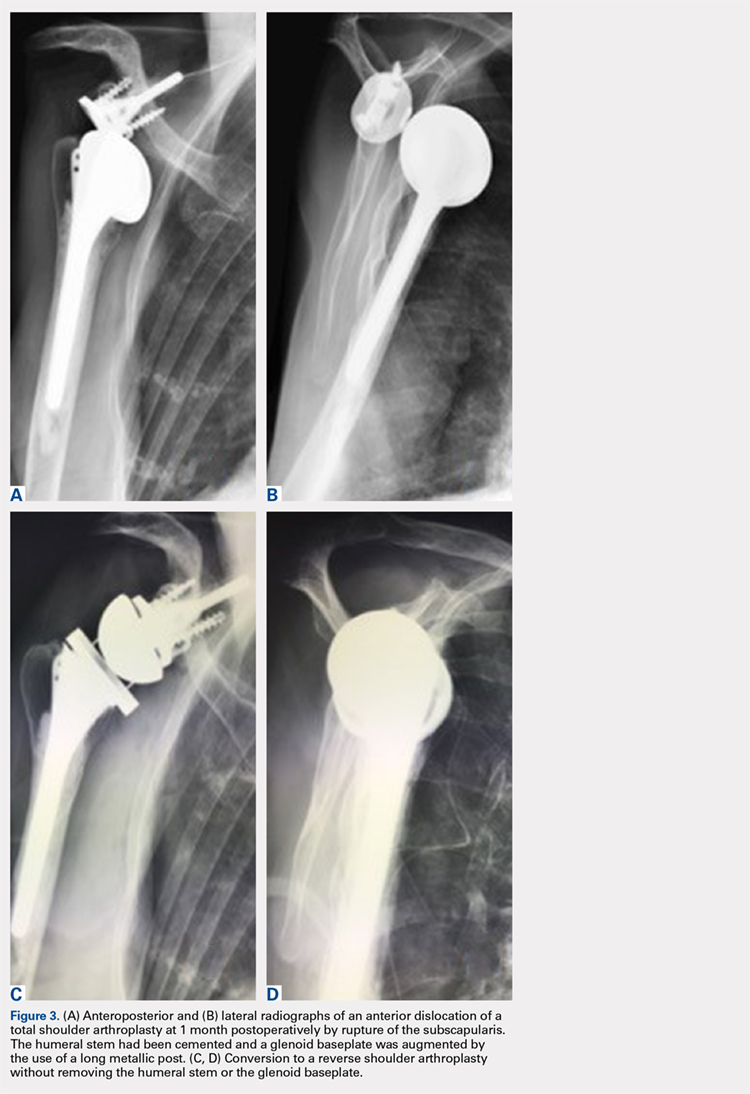

In this retrospective study, failure of TSA with a metal-backed glenoid implant was successfully revised to RSA. In 10 patients, the use of a universal platform system allowed an easier conversion without removal of the humeral stem or the glenoid component (Figures 3A-3D). Twelve of the 13 patients were satisfied or very satisfied at the last follow-up. None of the patients were in pain, and the mean Constant score was 63. In all the cases, the glenoid baseplate was not changed. In 3 cases the humeral stem was changed without any fracture of the tuberosities of need for an osteotomy. This greatly simplified the revision procedure, as glenoid revisions can be very challenging. Indeed, it is often difficult to assess precisely preoperatively the remaining glenoid bone stock after removal of the glenoid component and the cement. Many therapeutic options to deal with glenoid loosening have been reported in the literature: glenoid bone reconstruction after glenoid component removal and revision to a hemiarthroplasty (HA),10,16-18 glenoid bone reconstruction after glenoid component removal and revision to a new TSA with a cemented glenoid implant,16,17,19,20 and glenoid reconstruction after glenoid component removal and revision to a RSA.12,21 These authors reported that glenoid reconstruction frequently necessitates an iliac bone graft associated with a special design of the baseplate with a long post fixed into the native glenoid bone. However, sometimes implantation of an uncemented glenoid component can be unstable with a high risk of early mobilization of the implant, and 2 steps may be necessary. Conversion to a HA,10,16-18 or a TSA16,17,19,20 with a new cemented implant have both been associated with poor clinical outcome, with a high rate of recurrent glenoid loosening for the TSAs.

In our retrospective study, we reported no intra- or postoperative complications. Flury and colleagues22 reported a complication rate of 38% in 21 patients after conversion from a TSA to a RSA with a mean follow-up of 46 months. They removed all the components of the prosthesis with a crack or fracture of the humerus and/or the glenoid. Ortmaier and colleagues23 reported a rate of complication of 22.7% during the conversion of TSA to RSA. They did an osteotomy of the humeral diaphysis to extract the stem in 40% of cases and had to remove the glenoid cement in 86% of cases with severe damage of the glenoid bone in 10% of cases. Fewer complications were found in our study, as we did not need any procedure such as humeral osteotomy, cerclage, bone grafting, and/or reconstruction of the glenoid. The short operative time and the absence of extensive soft-tissue dissection, thanks to a standard deltopectoral approach, could explain the absence of infection in our series.

Other authors shared our strategy of a universal convertible system and reported their results in the literature. Castagna and colleagues24 in 2013 reported the clinical and radiological results of conversions of HA or TSA to RSA using a modular, convertible system (SMR Shoulder System, Lima Corporate). In their series, only 8 cases of TSAs were converted to RSA. They preserved, in each case, the humeral stem and the glenoid baseplate. There were no intra- or postoperative complications. The mean VAS score decreased from 8 to 2. Weber-Spickschen and colleague25 reported recently in 2015 the same experience with the same system (SMR Shoulder System). They reviewed 15 conversions of TSAs to RSAs without any removal of the implants at a mean 43-month follow-up. They reported excellent pain relief (VAS decreased from 8 to 1) and improvement in shoulder function with a low rate of complications.

Kany and colleagues26 in 2015 had already reported the advantages of a shoulder platform system for revisions. In their series, the authors included cases of failure of HAs and TSAs with loose cemented glenoids and metal-backed glenoids. The clinical and radiological results were similar, with a final Constant score of 60 (range, 42-85) and a similar rate of humeral stems which had to be changed (24%). These stems were replaced either because they were too proud or because there was not enough space to add an onlay polyethylene socket.

Continue to: Despite the encouraging results...