IN VIVO STUDY METHODS

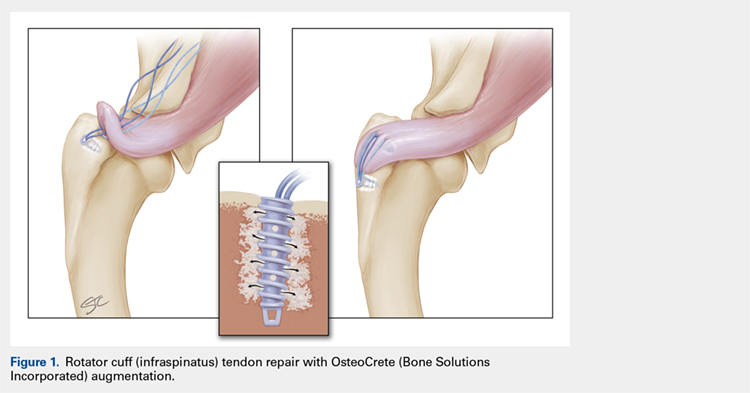

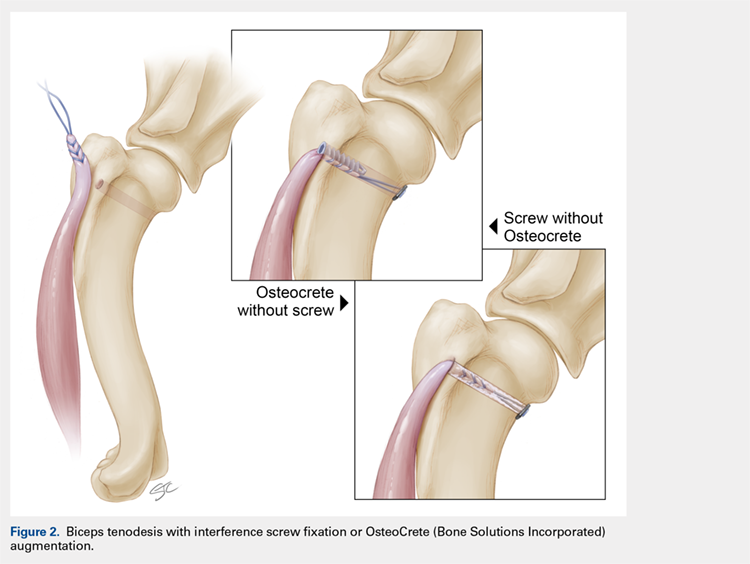

With Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval, adult (age, 2-4 years) purpose-bred dogs (N = 8) underwent aseptic surgery of both forelimbs for rotator cuff (infraspinatus) tendon repair (Figure 1) and biceps tenodesis (Figure 2). For the rotator cuff repair, two 4.75-mm vented anchors (1 medial and 1 lateral) with FiberTape were used in a modified double-row technique to repair the acutely transected infraspinatus tendon. In one limb, 1 ml of OsteoCrete was injected through both anchors; the other limb served as the uninjected control. For the biceps tenodesis procedure, the long head of the biceps tendon was transected at its origin and whip-stitched. The tendon was transposed and inserted into a 7-mm diameter socket drilled into the proximal humerus using a tension-slide technique with a transcortical button for fixation. In one limb, 1 ml of OsteoCrete was injected into the socket prior to final tensioning and tying. In the contralateral limb, a 7-mm interference screw (Bio-Tenodesis™ Screw, Arthrex) was inserted into the socket after tensioning and tying. The dogs were allowed to perform out-of-kennel monitored exercise daily for a period of 12 weeks after surgery and were then sacrificed.

The infraspinatus and biceps bone-tendon-muscle units were excised en bloc. Custom-designed jigs were used for biomechanical testing of the bone-tendon-muscle units along the anatomical vector of muscle contraction. Optical markers were mounted at standardized anatomical locations. Elongation of the repair site was defined as the change in distance between markers and was measured to 0.01-mm resolution using an optical tracking system (Optotrak Certus, NDI), synchronized with measurement of the applied tension load. The bone-tendon-muscle units were loaded in tension to 3-mm elongation at a displacement controlled rate of 0.01 mm/s. Load at 1-mm, 2-mm, and 3-mm displacement of the tendon-bone junction was extracted from the load vs the displacement curve of each sample. Stiffness was calculated as the slope of the linear portion of the load vs the displacement curve.19,20

For histologic assessments, sections of each treatment site were obtained using a microsaw and alternated between decalcified and non-decalcified processing. For decalcified bone processing, formalin-fixed tissues were placed in 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid with phosphate-buffered saline for 39 days and then processed routinely for the assessment of sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), toluidine blue, and picrosirius red. For non-decalcified bone processing, the tissues were dehydrated through a series of graded ethyl alcohol solutions, embedded in PMMA, sectioned, and stained with toluidine blue and Goldner’s trichrome. Two pathologists who were blinded to the clinical application and the differences between techniques assessed the histologic sections and scored each section using the modified Bonar score that assesses cell morphology, collagen arrangement, cellularity, vascularity, and extracellular matrix using a 15-point scale, where a higher score indicates more pathology.21

Categorical data were compared for detecting statistically significant differences using the rank sum test. Continuous data were compared for identifying statistically significant differences using the t-test or one-way ANOVA. Significance was set at P < .05.

RESULTS

IN VITRO RESULTS

OsteoCrete-augmented anchors (mean = 225 N; range, 158-287 N) had significantly (P < .001) higher pull-out load-to-failure compared to that in the uninjected controls (mean = 161 N; range, 68-202 N), which translated to a 50% mean increase (range, 3%-134%) in load-to-failure (Table 1). For humeri with reduced bone quality (control anchors that failed at <160 N, 4 humeri), the mean increase in load-to-failure for OsteoCrete-augmented anchors was 99% (range, 58%-135%), with the difference between mean values being again significantly different (OsteoCrete mean = 205 N; control mean = 110 N, P < .001). When the control and OsteoCrete load-to-failure values were compared using Pearson correlation, a significantly strong positive correlation (r = 0.66, P = 0.02) was detected. When the control load-to-failure values were compared with its percent increase value when OsteoCrete was used, there was a significantly very strong negative correlation (r = −0.90, P < .001).

Table 1. Cadaveric Lateral Row Rotator Cuff Anchor Pull-To-Failure; Testing Occurred 15 Minutes Post-Injection

| Humerus No. | Control (N) | OsteoCrete (N)a | Percent Increase |

| 1-Right (PA) | 197.28 | 278.73 | 41% |

| 1-Left (AP) | 152.62 | 241.72 | 58% |

| 2-Right (PA) | 178.60 | 196.03 | 10% |

| 2-Left (AP) | 170.10 | 175.57 | 3% |

| 3-Right (PA) | 67.70 | 158.31 | 134% |

| 3-Left (AP) | 74.24 | 173.08 | 133% |

| 4-Right (PA) | 195.81 | 248.12 | 27% |

| 4-Left (AP) | 201.95 | 209.42 | 4% |

| 5-Right (PA) | 173.30 | 220.59 | 27% |

| 5-Left (AP) | 146.61 | 247.37 | 69% |

| 6-Right (PA) | 171.03 | 266.14 | 56% |

| 6-Left (AP) | 199.99 | 286.91 | 43% |

| Average | 160.77 + 45.60 | 225.17 + 43.08 | 50% + 44 |

aOsteoCrete (Bone Solutions Incorporated) resulted in significantly increased (P < 0.001) pull-to-failure. Abbreviations: AP, control anchor located in anterior position, OsteoCrete anchor located in posterior position; PA, control anchor located in posterior position, OsteoCrete anchor located in anterior position.

Continue to: IN VIVO RESULTS