The tibia is the most commonly fractured long bone in adults, and tibial malunions occur in up to 60% of these patients.1,2 Persistent tibial malalignment, particularly varus alignment, negatively alters gait and joint kinematics, leading to altered weight-bearing forces across the knee and ankle joints. These altered forces may lead to osteoarthritis.3-8

Several studies have identified a relationship between extent of tibial malalignment and changes in joint reaction forces.3,5-7,9-13 Puno and colleagues14 developed a mathematical model to better define the changes in neighboring joints relative to the pattern of the tibia malalignment. Not surprisingly, their work showed that, with distal tibial malunions, altered stress concentrations were realized at the ankle joint, and more proximal tibial deformities led to larger alterations in the joint stresses at the knee. More recently, van der Schoot and colleagues8 found a high prevalence of ipsilateral ankle osteoarthritis with tibial malalignment of 5° or more, and Greenwood and colleagues15 showed a higher incidence of knee pain, lower limb osteoarthritis, and disability in patients with previous tibia fractures. Given these findings, it would seem that correction of tibial malalignment would lead to normative lower extremity joint kinematic values, joint reaction forces, and overall quality of life (QOL).

The ability to ambulate has been recognized as an important milestone in functional recovery after lower extremity injury.2,16,17 Gait analysis, assessment of joint kinematics, and QOL and health status questionnaires can provide information to evaluate rehabilitation protocols, treatment algorithms, and surgical outcomes. Recently, these measures have been used to assess patients recovering from acetabular fractures, femoral shaft fractures, and calcaneal fractures.4,11,17-24 However, no study has used these measures to assess the benefits of surgical correction of malaligned tibias.

We conducted a study to determine improvement in gait, joint kinematics, and patients’ perceptions of overall well-being after surgical correction of tibial malunions. The null hypothesis was that correction of tibial malunion would have no effect on gait, joint kinematics, or patients’ perceptions of function and QOL.

Materials and Methods

This prospective double-time-point study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Washington University/Barnes-Jewish Hospital, evaluated 11 consecutive patients with a varus tibial malunion treated by a single surgeon between September 2003 and January 2006. All patients were treated using a technique that included oblique osteotomy and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) or osteotomy and intramedullary nailing. Study inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older; symptomatic varus malunion of the tibia of 10º or more; absence of a developmental or pathologic process leading to the fracture and subsequent deformity; no neurologic deficit of either lower extremity or contralateral lower extremity deformity; and ability to ambulate 9 meters with or without use of an assistive device.

The 11 patients (6 men, 5 women) who met these criteria enrolled in the study. Mean age was 53 years (range, 43-68 years). Eight malunions involved the left tibia. The mechanisms of injury were motor vehicle crash (6 patients), fall from a great height (3), being struck by a motor vehicle (1), and gunshot (1). Mean time from injury to corrective surgery was 16.9 years (range, 1-34 years). Before surgery, each patient had a thorough physical examination, with plain radiographs, including anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views, obtained to assess degree of limb malalignment. Patients completed the Short Form-36 (SF-36) and the Musculoskeletal Function Assessment (MFA) and underwent joint kinematics and gait analysis. Five malunions were located in the mid-diaphysis of the tibia, 3 in the proximal third, and 2 in the distal third of the tibial shaft. One patient had posttraumatic deformity involving the proximal and the mid-diaphysis (Table 1). After surgery, each patient was followed at regular intervals in the surgeon’s private office. Minimum follow-up was 7 months (mean, 11 months; range 7-17 months). At follow-up, radiographs were obtained, and each patient completed the SF-36 and the MFA and underwent joint kinematics and gait analysis.

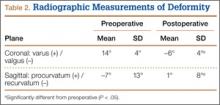

We obtained preoperative AP and lateral radiographs of the malaligned and contralateral normal tibias for each patient. Angular deformity was determined in the sagittal and coronal planes to determine location and magnitude of the deformity. Specifically, on each AP and lateral radiograph, a line was drawn the length of the tibia proximal and distal to the area of the deformity. The angle generated by the intersection of these lines on the AP and lateral radiographs was then plotted on a grid to determine the precise plane and magnitude of the deformity (Table 2).1,12 Clinically, relevant rotational deformity of the involved limb was assessed by physical examination, and the results were compared with those of the contralateral limb. Owing to the lack of considerable rotational deformity in any of these 11 patients, we did not obtain computed tomography scans for further assessment of rotation.