Carcinoma of the lung is the most common lethal form of cancer in both men and women worldwide.1 It accounts for more deaths than the next 3 most common cancers combined. In 2012, 160,000 Americans are estimated to have died from lung cancer.1 Lung cancer is known to have a high metastatic potential for the brain, bones, adrenal glands, lungs, and liver.2 Orthopedic manifestations frequently include bony metastasis, most commonly the vertebrae (42%), ribs (20%), and pelvis (18%).3 Acral metastatic disease is defined as metastasis distal to the elbow or the knee. Bony acral metastases from lung carcinoma to the upper and lower extremities are extremely uncommon, accounting for only 1% each of total bone metastases from carcinoma of the lung.3 Metastases to the bones of the hand are even rarer. Only 0.1% of metastatic disease from any type of carcinoma or sarcoma manifests as metastasis in the hand.4 There are only a few reports in the literature of soft-tissue or muscular metastasis to the hand from a carcinoma. Of these cases, the majority are caused by metastatic lung carcinoma.5-9 There are no reports in the literature of metastatic disease of squamous cell origin affecting the soft tissues of the hand.

We present a case of a man with known metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the lung who presented with acral soft-tissue metastatic disease. This report highlights a rare clinical scenario that has not been reported in the literature. The report also emphasizes a rare but important consideration for clinicians who encounter acral soft-tissue lesions in patients with a history of a primary carcinoma. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

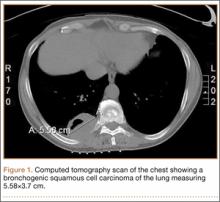

A 56-year-old man presented with right-sided pleuritic flank pain, along with a 30-lb weight loss over a 6-month period. A computed tomographic scan revealed a 5.58×3.7-cm cavitary lesion in the right lower lobe with abutment of the posterior chest wall (Figure 1). He underwent biopsy and staging, and was found to be T3N1, with biopsy-proven well-differentiated bronchogenic squamous cell carcinoma. The patient then underwent right lower and middle lobectomy with concomitant en-bloc resection of the posterior portion of ribs 7 to 11, along with mediastinal lymph-node dissection with negative margins. After surgery, he was treated with 4 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and docetaxel.

Six months after surgery, the patient began to complain of right-hand pain isolated to the thenar eminence. He also described swelling and significant pain with active or passive movement of the thumb and with relatively mild-to-moderate palpation of the area. The patient reported that the functioning of his thumb deteriorated rapidly over the course of about 1 month. On physical examination, he was neurovascularly intact with no apparent deficit in sensation of his right hand. There was no erythema or overlying skin changes. His right thenar eminence was mildly enlarged as compared with the left, and a firm, focal mass was readily palpated. Range of motion at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb and index finger was limited because of pain. Thumb opposition was markedly limited. After a detailed history and physical examination, we were concerned about possible deep space infection, old hematoma, or possible metastatic disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was ordered to evaluate the palpable mass.

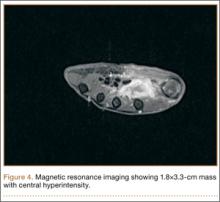

Radiographically, localized soft-tissue swelling was present on the palmar surface of the hand obliquely overlying the index finger metacarpal (Figures 2, 3). On MRI, the lesion measured approximately 1.8×3.3 cm and was isointense to slightly hyperintense diffusely with central hyperintensity on T1 images (Figure 4). On T2 and short tau inversion recovery images, the lesion was more strikingly hyperintense and infiltrative in appearance (Figure 5). Postcontrast images showed avid enhancement peripherally, with central nonenhancement consistent with necrosis in the adductor pollicis.

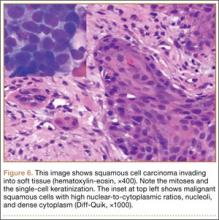

We performed a biopsy of the lesion with the aid of immediate adequacy by fine needle aspiration cytology. We saw mitotically active malignant cells with large nuclei, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, nucleoli, and dense cytoplasm, suggesting a metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. Because infection was part of the differential, it is pertinent to note that there was no significant inflammatory infiltrate. The core biopsy was consistent with metastatic lung cancer (Figure 6).

Discussion

This patient presented an interesting diagnostic challenge, particularly because of his previous malignancy. The differential diagnosis of acute onset thenar pain without history of trauma would include encompassing soft-tissue abscess, osteomyelitis, and infectious myositis. Soft-tissue hematoma is also in the differential for this patient, especially given the malignancy. Bony metastasis should be considered in this patient given the propensity of lung carcinoma to metastasize to bone. The location would certainly be atypical, with metastasis to the bones of the forearm or hand representing only 0.1% of all metastasis of any type of primary carcinoma or sarcoma.4 Primary bone or soft-tissue sarcoma should also be considered. Some authors have also suggested that necrosis, peritumoral edema-like signal, and lobulation are more common with skeletal muscle metastasis than with a primary sarcoma.10 In this case, the degree of surrounding postcontrast enhancement made simple muscle tear with hematoma unlikely, despite the presence of increased T1 signal. The lack of evidence for localized infection and the presence of a firm focal mass on physical examination made tumor more likely than infection.