Postoperative rehabilitation consists initially of pendulum exercises and scapular retraction starting on postoperative day 1. Once the swelling from the surgical procedure subsides, typically within 1 week, passive and active-assisted ROM and gentle posterior capsular mobilization are initiated under the direction of a licensed physical therapist. Active ROM is allowed once the patient regains normal scapulothoracic rhythm. Strengthening consists initially of isometrics followed by light resistance strengthening for the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers once active ROM and scapulothoracic rhythm return to normal. Passive internal rotation stretching, including use of the sleeper stretch, is implemented as soon as tolerated and continues throughout the rehabilitation process.32

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata Release 11 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Paired t tests were used to assess preoperative and postoperative mean differences in ASES scores, in passive glenohumeral internal rotation, and in active glenohumeral internal rotation; independent-samples t tests were used to assess side-to-side differences. Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

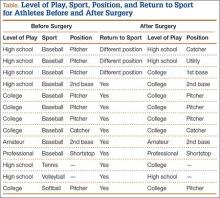

Fifteen overhead athletes met the study inclusion criteria. Two were lost to follow-up. Of the remaining 13 patients, 6 underwent isolated arthroscopic posterior-inferior capsular release, and 7 had concomitant procedures (6 subacromial decompressions, 1 superior labrum anterior-posterior [SLAP] repair). There were 11 male athletes and 2 female athletes. Twelve of the 13 patients were right-hand–dominant. Mean age at time of surgery was 21 years (range, 16-33 years). There were 10 baseball players (6 pitchers, 4 position players); the other 3 patients played softball (1), volleyball (1), or tennis (1). Six patients played at high school level, 5 at college level, 1 at professional level, and 1 at amateur level. All 13 patients underwent a minimum of 3 months of comprehensive rehabilitation, which included use of the sleeper stretch, active joint mobilization by a licensed physical therapist, and sport-specific restriction from exacerbating activities. Mean duration of symptoms before surgery was 18 months (range, 4-48 months). Mean postoperative follow-up was 31 months (range, 24-59 months). Mean ASES score was 71.5 (range, 33-95) before surgery and 86.9 (range, 60-100) after surgery (P < .001). Mean GIRD improved from 43.1° (range, 30°-60°) before surgery to 9.7° (range, –7° to 40°) after surgery (P < .001). Mean active internal rotation difference improved from 3.8 vertebral segments before surgery to 2.6 vertebral segments after surgery; this difference was not statistically significant (P = .459). Ten (77%) of the 13 patients returned to their preoperative level of play or a higher level; the other 3 (23%) did not return to their preoperative level of play but continued to compete in a different position (Table). Eleven patients (85%) stated they would repeat the procedure. One of the 2 patients who would not repeat the procedure was in the isolated posterior-inferior capsular release group; the other was in the concomitant-procedure group (subacromial decompression). Total glenohumeral ROM of dominant arm was 122° before surgery and 136° after surgery (P = .04). There was no significant difference in total ROM between dominant and nondominant arms after surgery (136° and 141°; P = .12), but the preoperative difference was significant (122° vs 141°; P = .022).

Discussion

GIRD has been associated with various pathologic conditions of the upper extremity. In 1991, Verna28 found that a majority of 39 professional baseball pitchers with significant GIRD had shoulder problems that affected playing time. More recently, GIRD has been associated with a progression of injuries, including scapular dyskinesia, internal and secondary impingement, articular-sided partial rotator cuff tears, rotator cuff weakness, damage to the biceps–labral complex, and ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency.12,18-22 In a cadaveric study of humeral head translation, Harryman and colleagues33 noted an anterosuperior migration of the humeral head during flexion and concluded it resulted from a loose anterior and tight posterior glenohumeral capsule, leading to loss of glenohumeral internal rotation. More recently, posterosuperior migration of the humeral head has been postulated, with GIRD secondary to an essential posterior capsular contracture.1 Tyler and colleagues34 clinically linked posterior capsular tightness with GIRD, and both cadaveric and magnetic resonance imaging studies have supported the finding that posterior capsular contracture leads to posterosuperior humeral head migration in association with GIRD.14,20 Such a disruption in normal glenohumeral joint mechanics could produce phenomena of internal or secondary acromiohumeral impingement and pain.

More recently, in a large cohort of professional baseball pitchers, a significant correlation was found between the incidence of rotator cuff strength deficits and GIRD.35 More than 40% of the pitchers with GIRD of at least 35° had a measureable rotator cuff strength deficit in the throwing shoulder.