Detection of thyroid cancer is widespread, increasing by about 4.5% annually. In the past year, approximately 64,300 new cases were identified. An estimated one in 100 people will be diagnosed with thyroid cancer during their lifetime, making it the eighth most common cancer in the United States.1

Incidental thyroid nodules found on carotid ultrasounds and other neck imaging may account for much of the increase; evaluation of these “incidentalomas” may account for the doubling incidence of thyroid cancer cases. (For more on thyroid nodules, see “To Cut or Not to Cut?” Clinician Reviews. 2016;26[8]:34-36.) If this pace continues, thyroid cancer may become the third most common cancer among women in the US by 2019.2

RISK FACTORS

Generally, women are diagnosed with thyroid cancer more frequently than men.3 Other risk factors include

- Age (40 to 60 in women; 60 to 80 in men; median age at diagnosis, 51)

- Inherited conditions, such as multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) or familial medullary and nonmedullary thyroid carcinoma

- Other cancers, including breast cancer and familial adenomatous polyposis

- Iodine deficiency

- Radiation exposure, particularly head and neck radiation in childhood. This can be through treatment of acne, tinea capitis, enlarged tonsils, or adenoids (usually prior to 1960); treatment of lymphoma, Wilms tumor, or neuroblastoma; or proximity to Chernobyl in 1986.1,2

BIOPSY RECOMMENDATIONS

While thyroid nodules are fairly common, only 7% to 15% of nodules are found to be malignant.2 However, all patients presenting with a palpable thyroid nodule should undergo thyroid ultrasound for further evaluation.

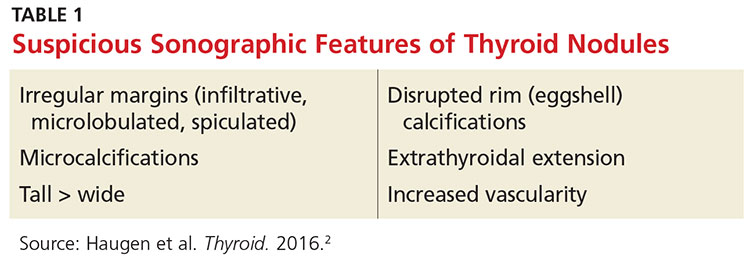

According to American Thyroid Association guidelines, all nodules 2 cm or larger should be evaluated with fine needle aspiration (FNA) due to a concern for metastatic thyroid cancer in larger nodules.2 Some clinicians prefer to aspirate nodules 1 cm or larger. Nodules that are smaller than 2 cm with sonographic features suspicious for thyroid cancer (see Table 1) should be biopsied.

Nodules that are spongiform in appearance or are completely cystic with no solid components may be monitored without FNA.2

The FNA is typically performed by an endocrinologist under ultrasound guidance. No anesthetic is required, but a topical ethyl chloride spray can assist with patient comfort. Three to four passes are made into the nodule with a 27-gauge needle; most patients describe pressure or a pinching sensation, rather than pain, during the procedure. After the procedure, ice applied to the FNA area may help with patient comfort.