Acute hypertensive episodes can also occur as a result of preeclampsia or eclampsia in pregnant women, pheochromocytoma, primary aldosteronism, glucocorticoid excess (Cushing syndrome), or central nervous system disorders (eg, cerebrovascular accident, head trauma, brain tumors).9,11,19

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

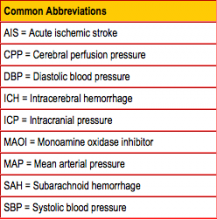

The purpose of the physical examination is to determine whether end-organ damage is present.1,11 The fundoscopic exam may reveal papilledema, a sign of increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Flame hemorrhages, cotton wool spots or arteriovenous nicking suggest a long-standing history of uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes.7,9 The neck should be assessed for jugular venous distention, which may be elevated in decompensated heart failure or pulmonary edema.11

The cardiac exam may reveal an irregular rate and rhythm, displaced apical pulse, gallop, or murmur. On pulmonary exam, rales may be auscultated, suggestive of pulmonary edema.9,15

The abdominal exam should include listening for a renal artery bruit.1 The neurologic exam may demonstrate altered mental status (possibly indicating hypertensive encephalopathy) or focal findings, if the patient has had an underlying ischemic or hemorrhagic event.9

LABORATORY STUDIES AND IMAGING

In most cases, a serum chemistry panel is warranted to identify any renal dysfunction. Urinalysis may reveal proteinuria, possibly indicating renal damage.4,9,15

Any patient complaining of chest pain should have an ECG to look for ischemic changes or presence of a left bundle branch block, and serial cardiac enzymes to rule out acute coronary syndrome.15 Access to previous ECGs is helpful in differentiating between new and old conductive abnormalities.

A chest x-ray should be performed in patients who complain of shortness of breath and/or chest pain. A widened mediastinum can represent aortic dissection.4,15 Evidence of pulmonary edema should prompt the clinician to assess for left ventricular dysfunction or valvular insufficiencies by echocardiogram. Chest CT should be pursued in patients with clinical suspicion for dissection.1,15,20

Patients presenting with a headache or focal neurologic abnormalities warrant a head CT to rule out stroke.15 Urine drug screening is appropriate if the patient history suggests illicit drug use.12

"FIRST, DO NO HARM"

Treatment of hypertensive emergency and urgency varies from traditional treatment for hypertension. Aggressive blood pressure control in patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke has been associated with poorer patient outcomes.21,22 Thus, treating the patient and not the numbers is the first general recommendation for treatment of hypertensive emergency and urgency. It is important for the clinician to remember the Hippocratic oath, "First do no harm," when treating these patients.

Other general recommendations are derived from theory, physiology, and smaller clinical trials; their application must be individualized according to the patient's needs. These recommendations include aiming for a reduction in mean arterial blood pressure of no more than 10% to 25% within the first hour, a goal blood pressure of 160/90 mm Hg within the first 8 hours, and normalization of blood pressure over 8 to 24 hours.12

While the use of pharmacologic agents may be warranted, it is important to consider that elevated blood pressure may be a reaction to pain or stress and may be best treated alternatively. Recommendations for permissive hypertension in acute ischemic stroke will be discussed below.

TREATMENT: HYPERTENSIVE URGENCY

The treatment of hypertensive urgency is usually immediate and warrants close follow-up. Although elevated blood pressures can be alarming to the patient, hypertensive urgency usually develops over days to weeks.8 In this setting, it is not necessary to lower blood pressure acutely.12 A rapid decrease in blood pressure can actually cause symptomatic hypotension, resulting in hypoperfusion to the brain.5,6,8

After ruling out end-organ damage, the next step is to treat according to the guidelines for hypertensive urgency.5,6 These recommendations include the use of rapid-onset oral antihypertensive agents, such as clonidine, labetalol, or captopril.23 Use of these agents is only suggested for gradual, short-term reduction of blood pressure (ie, over 24 to 48 hours) while the patient is being monitored for potential hypertension-related organ damage, either in the emergency department or in an observational hospital setting.5,6,23

Once the short-acting agents have adequately reduced blood pressure, long-term agents can be chosen to prevent rebound hypertension.16 Patients are typically monitored for 24 hours in the hospital during this transition. Upon discharge, the patient should be scheduled for follow-up within one to two days.11 Patient education, including a discussion of medication adherence, weight loss, and reduced dietary salt, is key to prevent recurrences and optimize overall treatment compliance.

TREATMENT: HYPERTENSIVE EMERGENCY

Treatment of hypertensive emergency always warrants hospitalization, usually in the ICU.5,6 IV antihypertensive medications (eg, nicardipine, fenoldopam, labetalol, esmolol, phentolamine) are preferred. Their use often necessitates continuous blood pressure monitoring via arterial line, allowing the clinician to perform ongoing medication titration. In hypertensive emergencies, the purpose of treatment is to preserve brain, kidney, and heart function.4