THE STAGES

The four stages of gout are asymptomatic hyperuricemia, acute gout, intercritical gout, and chronic tophaceous gout.20

Only a small percentage (0.5% to 4.5%) of patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia will develop acute gout.28 Nevertheless, any patient with serum urate greater than 6.8 mg/dL is at risk for the deposition of MSU crystals into body tissues and the potential associated organ damage—even patients without symptoms. There is currently no evidence-based method to determine which patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia will experience disease progression.16

Acute gout develops when deposition of MSU crystals in the joints initiates an inflammatory response. In the typical history, the patient experiences sudden-onset severe pain, swelling, and erythema. The pain often starts in the middle of the night or early morning,34 waking the patient from sleep and peaking within 24 hours of onset. At this time, the patient is often unable to bear weight comfortably on the affected joint. The patient may also report fever and flu-like malaise resulting from the release of interleukin 1- (IL-1), IL-1 receptor, cytokines, and prostaglandins.16,24,35 Usually in these early attacks, symptoms resolve spontaneously within three to 14 days.16,24

After resolution of an acute attack, the patient enters the intercritical stage, another asymptomatic stage that may last for months or years—or indefinitely. During the intercritical stage, MSU crystal deposition continues, adding crystals in and around the affected joint or joints, possibly continuing to inflict damage (in some patients, substantial), and in many cases resulting in additional attacks and pain.16 Any subsequent acute gout attacks the patient may experience are likely to last longer than the initial attack and to involve additional joints or tendons.24

Some patients, especially those who do not receive adequate treatment for hyperuricemia,2 progress to develop chronic tophaceous gout. This is a deforming disease process in which the joints may become stiff and swollen, and subcutaneous nodules or whitish-yellow intradermal deposits may be present under taut skin, anywhere in the body.16

PATIENT PRESENTATION AND HISTORY

Typically, a patient with gout will present with a chief complaint of a painful, tender, inflamed joint (classically described in Latin as calor, rubor, dolor, et tumor6). However, clinicians must also be aware of unusual presentations and consider gout in the differential whenever a patient with a history of gout or pertinent risk factors presents with unexplained clinical findings.32 The history of present illness will vary according to the stage of the disease.

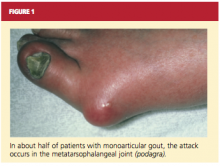

About 90% of recognized initial attacks of gout are monoarticular, usually occurring in one of the lower extremities.16 While the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint is affected in about 50% of gout cases (podagra, the Greek term for gout),2,35 eventually patients with gout have a 90% chance of involvement with the MTP joint (see Figure 1). According to Zhang et al,26 patients with hyperuricemia and an affected MTP joint have an 82% chance of having gout.2,26

Because such a large proportion of patients have the classic presentation of rapid-onset warmth, redness, and tenderness at the MTP, knee, or ankle and surrounding soft tissue, cases with a differing presentation are likely to be misdiagnosed or overlooked, or a correct diagnosis is delayed.26 In many documented cases, gout was the ultimate diagnosis—but one that was reached only incidentally because of unusual clinical presentation, ranging from entrapment neuropathy to a pancreatic mass.32

The presence of hyperuricemia and other risk factors must be investigated. Also relevant in the history of an acute gout attack may be a preceding event that has caused damage or stress to the joint, such as infection, trauma, or surgery. Other possible triggers for an attack include alcohol ingestion, acidosis, use of IV contrast media, diuretic therapy, chemotherapy, recent hospitalization or surgery, and initiation or termination of urate-lowering therapy with the xanthine oxidase inhibitor allopurinol.2,30 According to Primatesta et al,8 the risk for flares is increased in patients with cardiometabolic comorbidities.

The medication history of a patient with gout may include low-dose aspirin (but not standard-dose aspirin, which is uricosuric2), diuretics, cyclosporine, cytotoxic agents, and vitamin B12, which may contribute to hyperuricemia.24 Additionally, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, levodopa, nicotinic acid, didanosine, niacin, and warfarin may raise uric acid levels.15,30,33

Medical history should include a thorough assessment of the comorbidities associated with gout. In addition to the conditions mentioned previously, patients with a history of polycystic kidney disease, dehydration, lactic acidosis, hyperparathyroidism, toxemia of pregnancy, hypothyroidism, or sarcoidosis may have elevated urate levels due to underexcretion—and thus may be vulnerable to gout.30 History of gout in a first-degree relative is associated with an increased risk for gout.36