CDC GUIDELINES

Subject to state and federal regulations and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) directives, the CDC states that the goals of a TB infection control plan are

• Prompt detection of suspected or confirmed TB infection

• Airborne precautions implemented to reduce risk for TB transmission in areas in which exposure can occur

• Treatment of persons with suspected or confirmed TB.14

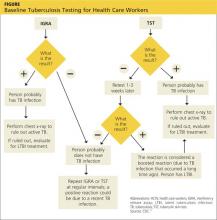

TB screening for HCWs has historically been a challenge in that, for new hires, the CDC recommends a baseline two-step process (meaning up to four visits) when TST is used.15 This is because TST-tested individuals may test false negative, even if they have LTBI, if many years have passed since their infection was acquired. As a result, guidelines for baseline testing are that, if the initial TST is negative, TST should be repeated one to three weeks later. If the person is in fact infected with TB, the first TST may stimulate the immune system’s ability to react to the TB antigens and elicit a positive or “boosted” response to the second test.

The above figure has been corrected from the print version as of December 16, 2014.

The 2005 guidelines recommended screening new-hire HCWs with either a baseline two-step TST or with one blood assay for M tuberculosis. After the introduction of the QFT-GIT and T-SPOT.TB tests, the CDC included them in its updated 2010 guidelines and indicated that either IGRAs or TSTs may be used in HCW surveillance programs for occupational exposure to M tuberculosis (see Figure).15,16 The algorithm clearly illustrates how the use of IGRAs in place of TSTs streamlines the process of HCW TB screening.17

EVALUATION OF TESTS

Given the stringent nature of the CDC’s TB infection control goals, it is essential that health care facilities use the most effective and efficient means for timely and thorough screening of HCWs for TB. When evaluating the available tests, the following factors must be considered: accuracy and reproducibility of test results; impact on results when testing is repeated frequently; interpretation of discordant test results; and specificity, sensitivity, and identification of appropriate test cutoff values so that a positive result signifies a new TB infection (ie, conversion, a change from a documented negative to positive test result within a two-year period) rather than a false positive; and costs.18,19

Accuracy

Unlike TSTs, IGRAs do not produce false-positive results in individuals vaccinated with BCG or in those infected with most nontuberculous mycobacteria.9,16 Neither TSTs nor IGRAs, however, can distinguish between active and latent TB infection.19 If either test is positive, a chest radiograph is indicated. If the x-ray reveals abnormalities in the lungs, a sputum smear to detect acid-fast-bacilli (AFB), of which M tuberculosis is one, is indicative of TB. Nuclear acid amplification testing of a respiratory specimen provides rapid laboratory confirmation, but a positive culture for M tuberculosis confirms the diagnosis.22

Specificity and sensitivity

Pai, Zwerling, and Menzies conducted a meta-analysis of 38 studies of TB testing. Most of the studies were small and had limitations, such as the lack of a gold standard test for the diagnosis of LTBI and variable TST methods and cutoff values. Nevertheless, the researchers were able to conclude that IGRAs are significantly more specific than TST and are unaffected by BCG vaccination. Although the sensitivity of IGRAs and TST is inconsistent across test populations, T-SPOT.TB appears to have greater sensitivity than QFT-GIT or TST.23

Further, TST is subject to variability in administration and interpretation, and cut points for TST positivity vary internationally.9 In contrast, the T-SPOT.TB test specifies a borderline result zone. According to the CDC, this increases test accuracy by classifying results near the cut point, making a subsequent test conversion from negative to positive more likely to represent newly acquired infection.16

On the other hand, some studies of IGRAs have found unexpectedly high rates of initial positive results and conversions among HCWs in low-risk settings that are later determined to be false positives.24 However, as noted previously, TSTs are also subject to false-positive results. In addition, the definition of an IGRA conversion is less stringent than the TST conversion definition, which may result in more IGRA conversions.16

Discordant results

Zwerling et al conducted a systematic review of all studies in which IGRAs were used for HCW screening to summarize their performance in cross-sectional and serial testing settings. The prevalence of positive IGRAs was found to be lower than that of positive TSTs. This difference was significant in low- and moderate-TB incidence settings but not in high-incidence settings. A positive association was reported between positive IGRA test results and occupational risk factors, including work in high-risk wards, TB clinics, and geriatric care, as well as length of employment.18

According to Mancuso et al, discordance of results between the TST and IGRAs in populations with low LTBI prevalence suggests that most positive test results are in fact false positives in these populations.25 Although IGRAs were designed to increase specificity, the authors found that IGRA specificity was no better than the specificity of TST. Without a gold standard for detecting M tuberculosis infection, assessing the true significance of discordance between TST and IGRAs is difficult. Further research is needed to determine the significance of test discordance, to obtain data on progression to active TB, and to better define appropriate cut points for interpreting IGRA results.25

Costs

The primary impediment to the widespread use of IGRAs has been cost, which is approximately three times that of a TST.24

Eralp et al studied the cost-effectiveness of IGRAs versus TST for screening for active LTBI in HCWs by using healthy life-years gained—defined as the number of TB cases avoided, yielding an increase in life expectancy—as the benefit metric rather than quality-adjusted life-years. Because testing is completed with a single visit, use of IGRAs increases compliance while minimizing resources needed for a second visit and eliminating loss to follow-up. Also notable is that IGRA testing takes place in a laboratory, where costs can be held in check with focused expertise and optimized staffing structures. The authors concluded that incremental IGRA costs per healthy life-year gained were justified.19

Until publication of the SWITCH (Screening health care Workers with IGRA vs. TST: impact on Costs and adHerence to testing) study in 2012, cost-effectiveness studies had shown inconsistent results. This study, conducted by The Johns Hopkins University (JHU) employee health department, was the first of its kind in the US to systematically analyze test performance and labor costs for TB screening of HCWs. The results showed that the time required to administer a TST is one of the costliest elements. For a sizeable institution such as JHU, TST screening cost more than $1.3 million annually, equivalent to approximately $73 per person; in contrast, IGRA screening amounted to less than $55 per person.26

Further research

The association between IGRA test conversion in HCWs and the risk for active TB disease has not been demonstrated.16 However, this is also true of TSTs27 and further research is needed in this area. Research is also needed to determine the significance of TSA-IGRA results discordance and to better define cut points for IGRA interpretation.25 In addition, more study of factors related to serial (periodic or ongoing) TB testing—which are very important within the context of HCW screening—is needed. As an example, serial TB testing may reveal trends in test conversions and can identify areas of concern within a health care facility. Unfortunately, current CDC recommendations do not provide specific guidelines for serial IGRA testing, such as guidance for accurate interpretation of IGRA results within a serial testing context.16 These areas should be addressed in future CDC updates.

Continue for conclusion >>