Spectators at baseball games may be exposed to excess solar UV radiation (UVR), which has been linked to the development of both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers.1,2 Although baseball hats traditionally are worn to demonstrate team support, they also may provide some sun protection for the head and face where skin cancers are commonly found.

The importance of protecting the skin from solar UVR has led to sun-protection programs and community education as well as efforts to evaluate the impact of these programs. Major League Baseball (MLB) has partnered with the American Academy of Dermatology since 1999 to promote the importance of sun protection and raise skin cancer awareness through its Play Sun Smart program.3 A study conducted 10 years ago (N=2030) evaluated hat use in spectators at MLB games and noted that less than half of all spectators in seating sections exposed to direct sunlight wore hats.4 The purpose of the current study was to evaluate how public education about sun protection has impacted the use of hats by spectators at MLB games in 2015 compared to the prior study in 2006.

Methods

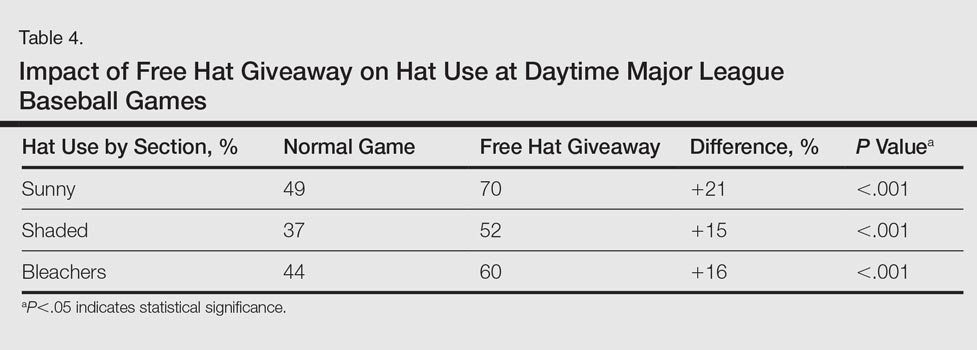

Data were collected during a 3-game series (2 day games, 1 night game) in August 2015 in New York, New York. During one of the day games, 18,000 fans received a free wide-brimmed hat. High-resolution digital photographs of seating sections were obtained using a camera with a 300-mm lens. Using the same methodology as the prior study,4 sunny and shaded seating sections were photographed during all 3 games (Figure). Photographs of each section were analyzed by an independent reviewer using a high-resolution computer screen. Spectators wearing head coverings—baseball hats, visors, or hats with circumferential brims—were defined as using hats. The number of spectators wearing hats versus not wearing hats was recorded for all identical sections of interest. Bleacher seating was analyzed separately, as spectators presumably knew in advance of the continuous direct sun exposure during day games, and a subset of young children in the bleachers (<10 years of age) also was assessed. A continuously sunny section also was evaluated at the second and sixth innings to see if hats were presumably purchased during exposure. Statistical significance was determined using χ2 tests with P<.05 indicating statistical significance.

Results

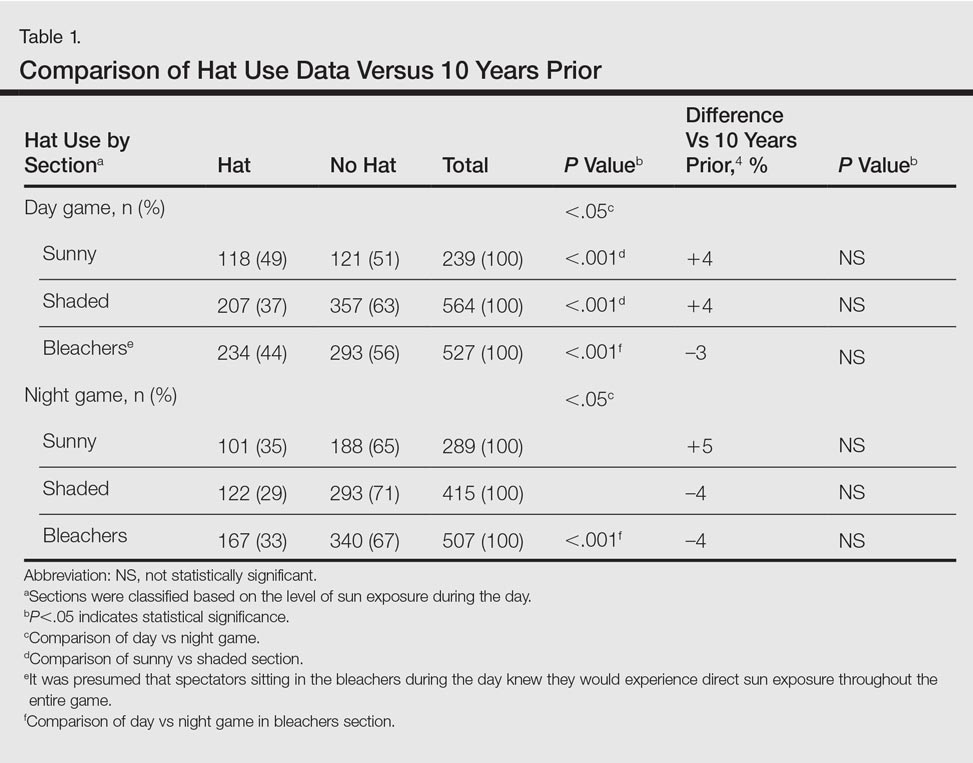

This analysis consisted of 3539 spectators. In both the sunny and shaded sections of a day game, there were more spectators wearing hats (49% and 37%, respectively)(P<.001) than in the same sections at night games (35% and 29%, respectively)(Table 1). During the day game, more spectators wore hats in the sunny section than in the adjacent shaded section (49% vs 37%; P<.001). Analysis of the same 2 sections during the night game revealed no significant differences.

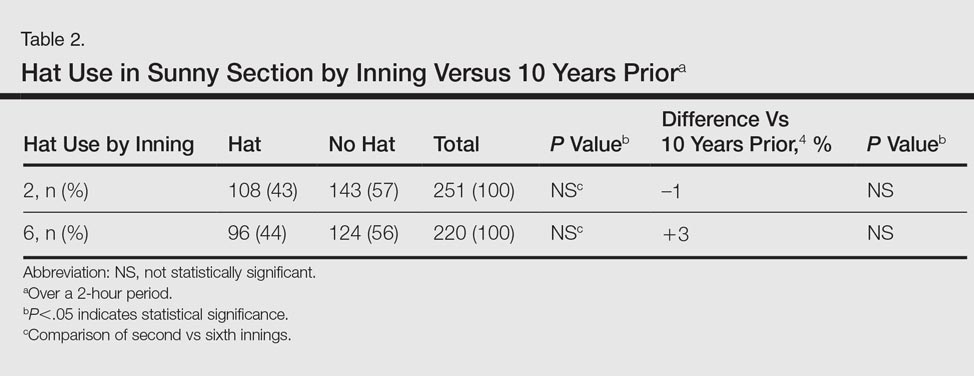

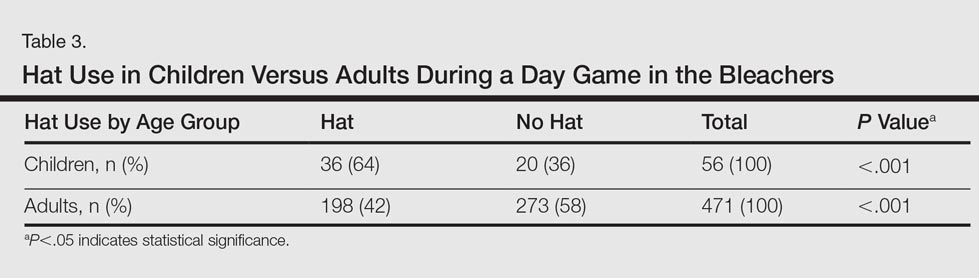

Spectators sitting in the bleachers during a day game who presumably knew to anticipate direct sun exposure showed no significant differences in hat-wearing patterns versus the sunny section (44% vs 49%) but were more likely to wear hats compared to those sitting in the bleachers at the night game (44% vs 33%)(P<.001)(Table 1). There was no significant difference in the number of hats worn by spectators in the sunny section in the second inning (43%) versus the same section after continuous sun exposure at the sixth inning (44%)(Table 2). Significantly more children seated in the bleachers during the day game wore hats compared to adults in the same section (64% vs 42%; P<.001)(Table 3). During the hat giveaway day, significantly more spectators wore hats (the majority of which were the free giveaway hats) across all sections studied (P<.001)(Table 4).