Dermpath Diagnosis

From the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Texas. Dr. Butler is from San Antonio Military Medical Center. Dr. Kobayashi is from Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the United States, US Air Force, or the Department of Defense. Both authors are active-duty military, which means the work here belongs in the public domain.

Correspondence: Jason N. Butler, DO, 3401 Williamsburg Ln, Texarkana, TX 75503 (jason.n.butler.mil@mail.mil).

Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia (TUGSE) is an underreported diagnosis in dermatologic literature. Rapid expansion with an ulcerative clinical appearance often provokes fear of malignancy despite its benign nature. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia is thought to be a reactive tissue response to trauma, but CD30+ mononuclear cells within a TUGSE lesion suggests the possibility of an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder. This case highlights the clinical and histological features of TUGSE and provides a brief review of the literature addressing this debate. Knowledge of this condition, which uncommonly presents to the practicing dermatologist, is important in providing appropriate patient care and counseling. When correctly identified, unnecessary therapies and emotional stress can be avoided.

Practice Points

Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia (TUGSE) is an uncommon, benign, self-limited condition that is restricted to the oral mucosa, most commonly seen in the fifth to seventh decades of life.1-3 The pathogenesis of TUGSE is unknown, but current theory suggests trauma is the instigating factor. The presence of CD30+ mononuclear cells within TUGSE raises the possibility of a CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder in some cases.4 However, because CD30+ cells are not uncommon in other benign reactive processes, they may simply represent a reactive phenomenon.3

Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia traverses multiple disciplines, including dermatology, oral surgery, dentistry, and pathology, resulting in a diverse nomenclature including traumatic granuloma of the tongue, traumatic eosinophilic granuloma of the oral mucosa, ulcerated granuloma eosinophilicum diutinum, and eosinophilic ulcer of the oral mucosa.1,4-6 It is important to differentiate eosinophilic granuloma of the oral mucosa from the eosinophilic granuloma that is associated with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Although both may present with oral ulceration, Langerhans cell–associated eosinophilic granuloma typically develops from underlying bone, whereas eosinophilic granuloma of the oral mucosa (TUGSE) is described as nonosseous.7,8 Furthermore, the gingiva is the most common oral site in Langerhans cell–associated eosinophilic granuloma, whereas the tongue is most commonly involved in TUGSE.8 Shapiro and Juhlin9 clearly distinguished TUGSE from Langerhans cell–associated eosinophilic granuloma in 1970. Histologically, the 2 conditions are completely different.

When ulcerative granulomas develop in the pediatric population, usually in children younger than 2 years, it is termed Riga-Fede disease.10 These children were typically breastfeeding, suckling, or teething, suggesting trauma as a triggering event. In 1961, Hjorting-Hansen and Schmidt5 described 3 separate lesions similar to Riga-Fede disease in an adult patient. Subsequently, Riga-Fede disease was grouped under TUGSE.3

Histologically, TUGSE shows an ulcerated epithelium with a polymorphic inflammatory cell infiltrate that has a large predominance of eosinophils. The infiltrate affects the superficial and deep layers of the muscle tissue and penetrates into the salivary glands. Large atypical mononuclear cells with an ovoid and pale-appearing nucleus often are present. These cells may be mitotically active and stain positively for CD30.1,4,11 CD68+ macrophages, T lymphocytes, and factor XIIIa–positive dendritic cells commonly are present.12

Given the presence of large atypical CD30+ cells in many lesions, the possibility of a CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder has been postulated by some authors. Indeed, lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) has been documented to involve the oral mucosa.2,4

An 81-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging, 1.7×1.3-cm, vascular-appearing nodule with a collarette of mucosal epithelium on the left side of the dorsal surface of the tongue of 2 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). He denied any history of trauma, tobacco chewing, weight change, fever, or fatigue; however, he did report a 30 pack-year smoking history. There was no other pertinent medical history to include medications or allergies.

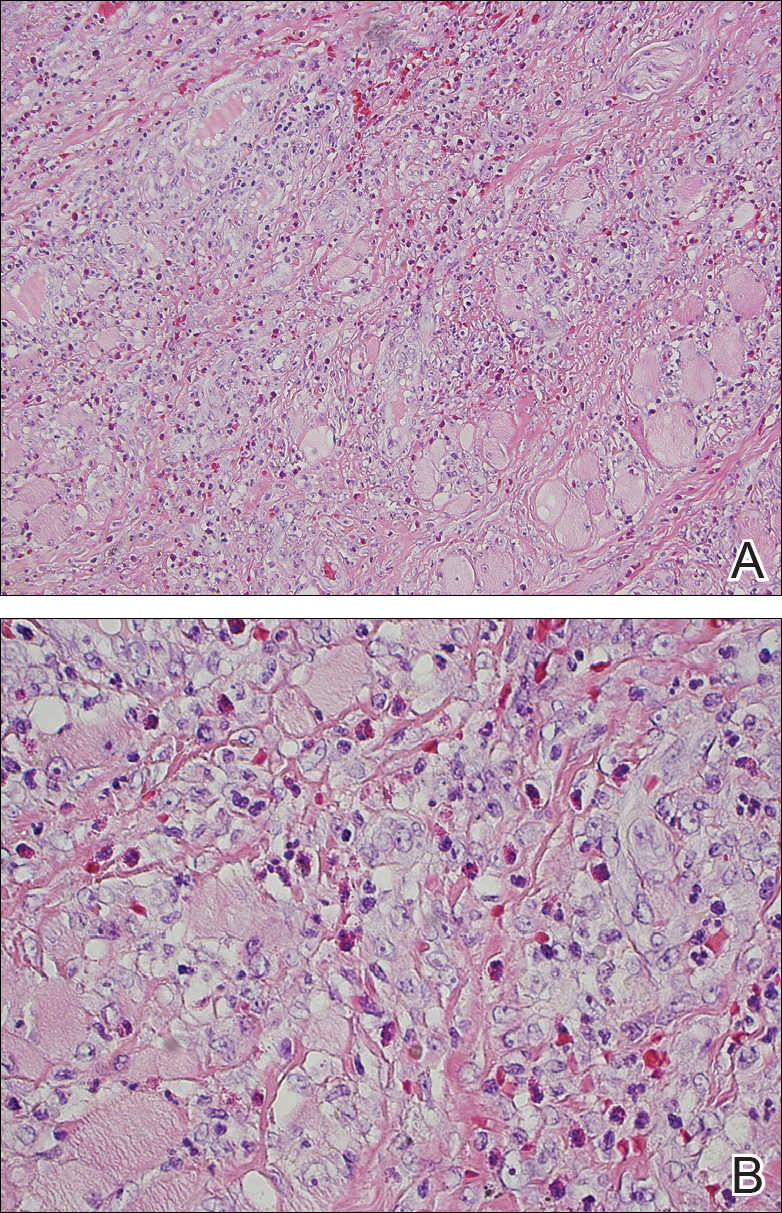

The differential diagnosis included pyogenic granuloma, granular cell tumor, squamous cell carcinoma, other neoplasms (eg, oral lymphoma, salivary gland tumors), and a traumatic blood blister from tongue biting. The patient was referred to the oral maxillofacial surgery department for an excisional biopsy, which showed a solitary ulcerated nodule with associated granulation tissue, thrombus, and fibrinoid debris (Figure 2). A surrounding dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils was noted extending through the submucosal tissue and underlying striated muscle fibers (Figure 3). The adjacent mucosal epithelium appeared normal. CD30 staining showed only rare positive cells. These findings were consistent with TUGSE.

Figure 3. Traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia histopathology consisting of a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils extending through the submucosal tissue and underlying striated muscle fibers (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×100 and ×400).

Due to the benign nature of TUGSE, the patient was released with symptomatic care and instructed to return for any new growth. The growth spontaneously resolved over 1 month and no recurrence or new lesions were reported 1 year later.

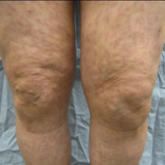

Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (CPAN) is a rare cutaneous small- to medium-vessel vasculitis of unknown etiology. Clinically it ranges in...