The term blueberry muffin rash historically was used to describe the cutaneous manifestations observed in congenital rubella. The term traditionally describes the result of a postnatal dermal extramedullary hematopoiesis. Today, TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other agents, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes) infections and plasma cell dyscrasias are all potential causes of extramedullary hematopoiesis. Herein, we present a unique case of a neonate born with a blueberry muffin rash secondary to extramedullary hematopoiesis induced by hereditary spherocytosis.

Case Report

The dermatology department was consulted to evaluate a 2-day-old male neonate born with a “rash.” The patient was born to a 34-year-old gravida 3, para 2, woman at 39 weeks’ gestation. The mother’s prenatal laboratory values were within reference range and ultrasounds were normal, and she was compliant with her prenatal care. She underwent a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery 3 hours after rupture of membranes without complication. The amniotic fluid and umbilical cord both were clear. There was no use of forceps or any other external aiding devices during the delivery. At the time of delivery, the consulting physician noted that the patient had “skin lesions from head to toe.”

The patient’s parents reported that the rash did not seem to cause any discomfort for the patient. In the 24 hours after birth, the parents reported that the erythema seemed to slightly fade. Physical examination revealed many scattered erythematous to violaceous, nonblanching papulonodules affecting the scalp (Figure 1), face, arms, hands (Figure 2A), back (Figure 2B), buttocks, legs, and feet. Some of the papulonodules were soft while others were firm and indurated. Several lesions had a yellowish hue with some overlying crust. There was no mucosal, genital, or ocular involvement. No erosions, ulcerations, petechiae, ecchymoses, or hepatosplenomegaly were noted on examination.

The patient was otherwise healthy with an Apgar score of 8/9 at 1 and 5 minutes. His birth weight, length, and head circumference were within normal limits. There was no evidence of ABO blood group or Rhesus factor incompatibility. His temperature, vital signs, laboratory values (including calcium level and TORCH titers, which included cytomegalovirus, rubella, toxoplasmosis, and herpes simplex virus), and review of systems all were within reference range. A bone survey of the skull, spine, ribs, arms, pelvis, legs, and feet was within normal limits.

The mother’s placenta was sent for pathology and revealed a lymphoplasmacytic chronic deciduitis and acute subchorionitis consistent with a nonspecific inflammatory response, unlikely to be from an infectious etiology.

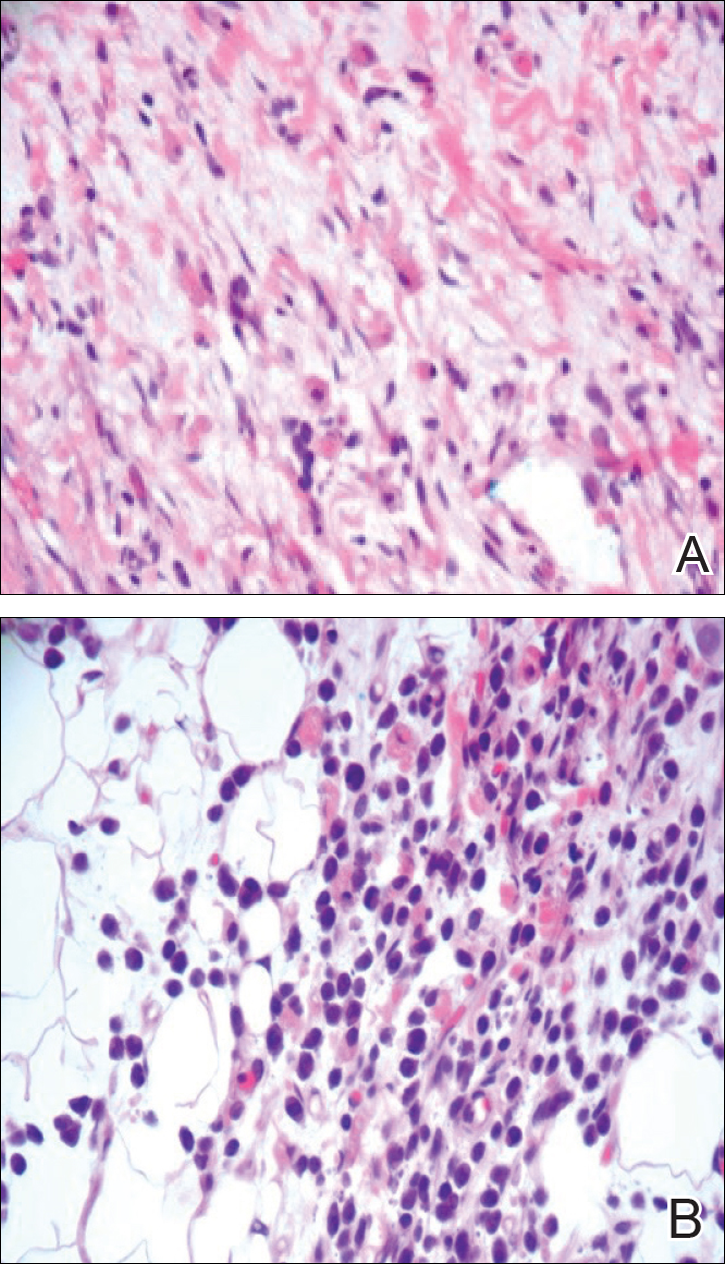

A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the left thigh and revealed a predominately lymphocytic infiltrate with rare eosinophils and erythrocyte precursors (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical staining was performed showing that the majority of the lymphocytes represented T lymphocytes, which stained positive for CD45 and CD3 and negative for S-100, CD1a, CD30, and CD117. There were scattered CD34+ cells, and scattered cells stained positive for myeloperoxidase. No significant CD20 immunoreactivity was noted. There were scattered eosinophils and rare normoblasts but no megakaryocytes. A complete blood cell count (CBC) with differential and reticulocyte count was within reference range.

At 1-, 3-, 8-, 12-, and 28-week follow-up visits, the patient continued to grow and feed appropriately. No new lesions developed during this time, and the preexisting lesions continued to fade into slightly hyperpigmented patches without induration (Figure 4). At 6 months of age, a CBC performed at the time of an upper respiratory infection and otitis media revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 9.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), a reticulocyte count of 0.8% (reference range, 0.5%–1.5%), and a lactate dehydrogenase level of 424 U/L (reference range, 100–200 U/L). All red blood cell (RBC) indices were within reference range. Flow cytometry, eosin-5-maleimide, and ektacytometry were performed with results consistent with mild hereditary spherocytosis.