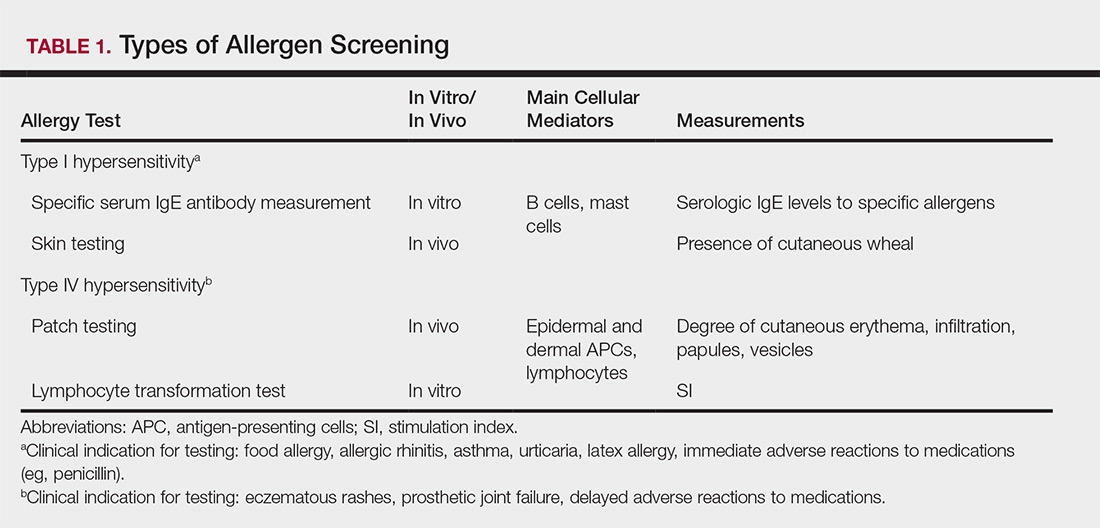

Allergy testing typically refers to evaluation of a patient for suspected type I or type IV hypersensitivity.1,2 The possibility of type I hypersensitivity is raised in patients presenting with food allergies, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and immediate adverse reactions to medications, whereas type IV hypersensitivity is suspected in patients with eczematous eruptions, delayed adverse cutaneous reactions to medications, and failure of metallic implants (eg, metal joint replacements, cardiac stents) in conjunction with overlying skin rashes (Table 1).1-5 Type II (eg, pemphigus vulgaris) and type III (eg, IgA vasculitis) hypersensitivities are not evaluated with screening allergy tests.

Type I Sensitization

Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate hypersensitivity mediated predominantly by IgE activation of mast cells in the skin as well as the respiratory and gastric mucosa.1 Sensitization of an individual patient occurs when antigen-presenting cells induce a helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response leading to B-cell class switching and allergen-specific IgE production. Upon repeat exposure to the allergen, circulating antibodies then bind to high-affinity receptors on mast cells and basophils and initiate an allergic inflammatory response, leading to a clinical presentation of allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or immediate drug reactions. Confirming type I sensitization may be performed via serologic (in vitro) or skin testing (in vivo).5,6

Serologic Testing (In Vitro)

Serologic testing is a blood test that detects circulating IgE levels against specific allergens.5 The first such test, the radioallergosorbent test, was introduced in the 1970s but is not quantitative and is no longer used. Although common, it is inaccurate to describe current serum IgE (s-IgE) testing as radioallergosorbent testing. There are several US Food and Drug Administration-approved s-IgE assays in common use, and these tests may be helpful in elucidating relevant allergens and for tailoring therapy appropriately, which may consist of avoidance of certain foods or environmental agents and/or allergen immunotherapy.

Skin Testing (In Vivo)

Skin testing can be performed percutaneously (eg, percutaneous skin testing) or intradermally (eg, intradermal testing).6 Percutaneous skin testing is performed by placing a drop of allergen extract on the skin, after which a lancet is used to lightly scratch the skin; intradermal testing is performed by injecting a small amount of allergen extract into the dermis. In both cases, the skin is evaluated after 15 to 20 minutes for the presence and size of a cutaneous wheal. Medications with antihistaminergic activity must be discontinued prior to testing. Both s-IgE and skin testing assess for type I hypersensitivity, and factors such as extensive rash, concern for anaphylaxis, or inability to discontinue antihistamines may favor s-IgE testing versus skin testing. False-positive results can occur with both tests, and for this reason, test results should always be interpreted in conjunction with clinical examination and patient history to determine relevant allergies.

Type IV Sensitization

Type IV hypersensitivity is a delayed hypersensitivity mediated primarily by lymphocytes.2 Sensitization occurs when haptens bind to host proteins and are presented by epidermal and dermal dendritic cells to T lymphocytes in the skin. These lymphocytes then migrate to regional lymph nodes where antigen-specific T lymphocytes are produced and home back to the skin. Upon reexposure to the allergen, these memory T lymphocytes become activated and incite a delayed allergic response. Confirming type IV hypersensitivity primarily is accomplished via patch testing, though other testing modalities exist.

Skin Biopsy

Biopsy is sometimes performed in the workup of an individual presenting with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and typically will show spongiosis with normal stratum corneum and epidermal thickness in the setting of acute ACD and mild to marked acanthosis and parakeratosis in chronic ACD.7 The findings, however, are nonspecific and the differential of these histopathologic findings encompasses nummular dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, and dyshidrotic eczema, among others. The presence of eosinophils and Langerhans cell microabscesses may provide supportive evidence for ACD over the other spongiotic dermatitides.7,8

Patch Testing

Patch testing is the gold standard in diagnosing type IV hypersensitivities resulting in a clinical presentation of ACD. Hundreds of allergens are commercially available for patch testing, and more commonly tested allergens fall into one of several categories, such as cosmetic preservatives, rubbers, metals, textiles, fragrances, adhesives, antibiotics, plants, and even corticosteroids. Of note, a common misconception is that ACD must result from new exposures; however, patients may develop ACD secondary to an exposure or product they have been using for many years without a problem.

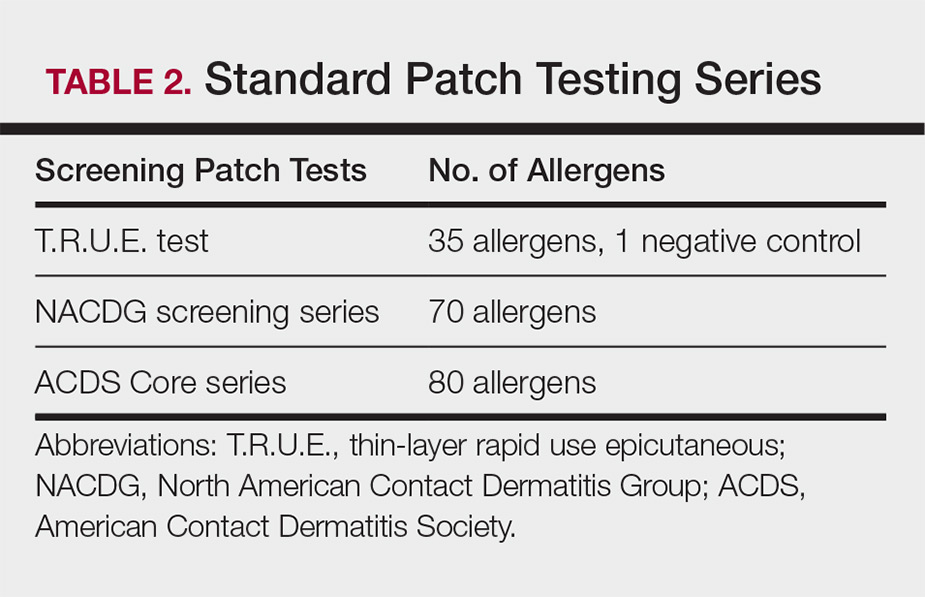

Three commonly used screening series are the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (SmartPractice), North American Contact Dermatitis Group screening series, and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 80 allergen series, which have some variation in the type and number of allergens included (Table 2). The T.R.U.E. test will miss a notable number of clinically relevant allergens in comparison to the North American Contact Dermatitis Group and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core series, and it may be of particularly low utility in identifying fragrance or preservative ACD.9

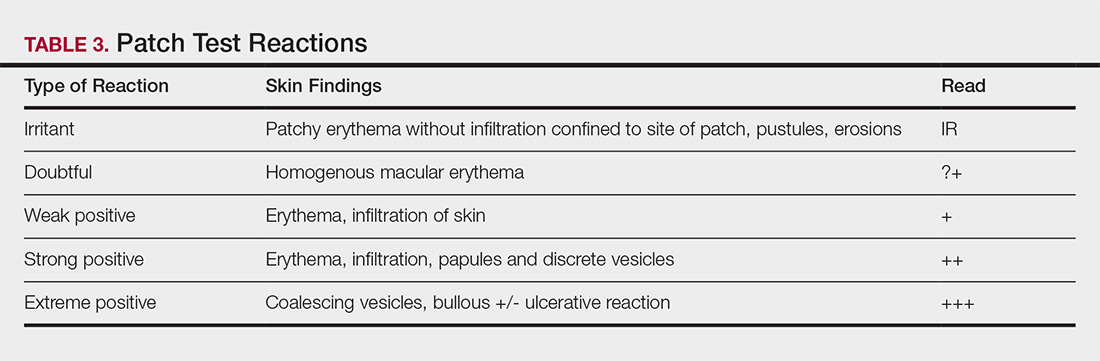

Allergens are placed on the back in chambers in a petrolatum or aqueous medium. The patches remain affixed for 48 hours, during which time the patient is asked to refrain from showering or exercising to prevent loss of patches. The patient's skin is then evaluated for reactions to allergens on 2 separate occasions: at the time of patch removal 48 hours after initial placement, then the areas of patches are marked for delayed readings at day 4 to day 7 after initial patch placement. Results are scored based on the degree of the inflammatory reaction (Table 3). Delayed readings beyond day 7 may be necessary for metals, specific preservatives (eg, dodecyl gallate, propolis), and neomycin.10

There is a wide spectrum of cutaneous disease that should prompt consideration of patch testing, including well-circumscribed eczematous dermatitis (eg, recurrent lip, hand, and foot dermatitis); patchy or diffuse eczema, especially if recently worsened and/or unresponsive to topical steroids; lichenoid eruptions, particularly of mucosal surfaces; mucous membrane eruptions (eg, stomatitis, vulvitis); and eczematous presentations that raise concern for airborne (photodistributed) or systemic contact dermatitis.11-13 Although further studies of efficacy and safety are ongoing, patch testing also may be useful in the diagnosis of nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions, especially fixed drug eruptions, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, systemic contact dermatitis from medications, and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome.3 Lastly, patients with type IV hypersensitivity to metals, adhesives, or antibiotics used in metallic orthopedic or cardiac implants may experience implant failure, regional contact dermatitis, or both, and benefit from patch testing prior to implant replacement to assess for potential allergens. Of the joints that fail, it is estimated that up to 5% are due to metal hypersensitivity.4

Throughout patch testing, patients may continue to manage their skin condition with oral antihistamines and topical steroids, though application to the site at which the patches are applied should be avoided throughout patch testing and during the week prior. According to expert consensus, immunosuppressive medications that are less likely to impact patch testing and therefore may be continued include low-dose methotrexate, oral prednisone less than 10 mg daily, biologic therapy, and low-dose cyclosporine (<2 mg/kg daily). Therapeutic interventions that are more likely to impact patch testing and should be avoided include phototherapy or extensive sun exposure within a week prior to testing, oral prednisone more than 10 mg daily, intramuscular triamcinolone within the preceding month, and high-dose cyclosporine (>2 mg/kg daily).14

An important component to successful patch testing is posttest patient counseling. Providers can create a safe list of products for patients by logging onto the American Contact Dermatitis Society website and accessing the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP).15 All relevant allergens found on patch testing may be selected and patient-specific identification codes generated. Once these codes are entered into the CAMP app on the patient's cellular device, a personalized, regularly updated list of safe products appears for many categories of products, including shampoos, sunscreens, moisturizers, cosmetic products, and laundry or dish detergents, among others. Of note, this app is not helpful for avoidance in patients with textile allergies. Patients should be counseled that improvement occurs with avoidance, which usually occurs within weeks but may slowly occur over time in some cases.

Lymphocyte Transformation Test (In Vitro)

The lymphocyte transformation test is an experimental in vitro test for type IV hypersensitivity. This serologic test utilizes allergens to stimulate memory T lymphocytes in vitro and measures the degree of response to the allergen. Although this test has generated excitement, particularly for the potential to safely evaluate for severe adverse cutaneous drug reactions, it currently is not the standard of care and is not utilized in the United States.16

Conclusion

Dermatologists play a vital role in the workup of suspected type IV hypersensitivities. Patch testing is an important but underutilized tool in the arsenal of allergy testing and may be indicated in a wide variety of cutaneous presentations, adverse reactions to medications, and implanted device failures. Identification and avoidance of a culprit allergen has the potential to lead to complete resolution of disease and notable improvement in quality of life for patients.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Nina Botto, MD (San Francisco, California), for her mentorship in the arena of ACD as well as the Women's Dermatologic Society for the support they provided through the mentorship program.