The English expression, “a pain in the neck” is said to have originated in the early 1900s as a euphemism for the less polite phrase, “a pain in the ass.”1 While one might wonder how the expressions of such disparate discomforts came to be idiomatically equivalent, the focus of this article is on etiology of the former. All wryness aside, since most ED presentations of neck pain are musculoskeletal in origin, one may easily fail to consider the myriad of less common, but possibly serious, causes.

Pain can originate from any part of the neck and occur as a result of inflammation (eg, infections and arthritides), vascular pathology (eg, cervical artery dissection [CAD]), spaceoccupying lesions (eg, hematomas, cysts, tumors), or even as referred pain from noncervical sources (eg, heart, diaphragm, lung apex). Any lesion encroaching on the limited space of the neck can quickly compromise the airway, compress nerves, or inhibit blood flow to the brain; therefore, knowledge of the causes of such conditions is critical. This article reviews some of the less common and generally atraumatic etiologies of nontraumatic neck pain of which the emergency physician should be familiar.

Vascular Disorders

Vascular-associated neck pain can originate from vessels within the neck or represent referred pain from a more distant structure. In both cases, however, the potential for morbidity is high and the need for consideration and timely recognition crucial.

Cervical Artery Dissection

The typical initial presenting symptom of CAD—ie, internal CAD (ICAD) or vertebral artery dissection (VAD)—is severe pain in the ipsilateral neck and/or head. Onset of pain may be sudden or gradual.2 CAD occurs in an estimated 2 or 3 of every 100,000 people per year, mostly in patients between ages 20 and 40 years, and it is considered the most common cause of stroke in patients younger than age 45 years.2 The pain associated with CAD generally follows trauma. While the precipitating trauma can be a major blunt or penetrating one, it is often caused by something seemingly trivial, such as “trauma” associated with coughing, painting a ceiling, yoga, or (classically and notoriously) chiropractic manipulation.3 There is frequently some rotational component to CAD-associated trauma,4 though dissection may occur spontaneously.5

The typical triad of symptoms is ipsilateral neck and/or head pain, partial Horner’s syndrome (ptosis and miosis without anhidrosis), and signs of cerebral ischemia. However, patients do not always present with all three of these symptoms, which can complicate the diagnosis. For example, in some patients, neck pain is the sole presenting symptom and can mimic the musculoskeletal pain expected from the mechanical strain that precipitated the dissection.6 In addition, partial Horner’s syndrome occurs in only 50% of cases, and ischemic symptoms might not present for hours to weeks after the onset of neck pain.6

In almost all cases of CAD, initial symptoms are otherwise unexplained pain described as a constant, steady aching. 7 Since cervical arteries are heavily invested with pain fibers,8 an intimal tear with dissecting intramural hematoma provokes pain. Pain associated with VAD is usually severe, unilateral, posterior neck, and/or occipital, while ICAD-associated pain is ipsilateral, anterolateral neck, head, and/or face. It is important to note that head or neck pain caused by a dissection normally precedes the ischemic manifestation as opposed to the more common stroke, in which the ischemia precedes or is simultaneous with the accompanying headache.9

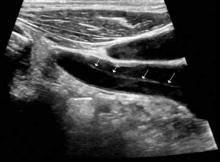

Ischemic neurological symptoms can arise from stenosis of the arterial lumen, secondary to an expanding intramural hematoma; a luminal thrombus developing at the intimal defect; or an embolization accompanied by ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, any cranial nerve abnormality, or followed by cerebral or ocular ischemic symptoms (even if transient). A diagnosis is usually made through vascular ultrasound (Figure 1) and confirmed with computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography. When requesting a CTA of the neck, the emergency physician should specifically make note of suspected CAD in the order. Immediate treatment includes a cervical collar and neurosurgical consultation even though treatment is essentially medical and surgery is rarely required. Anticoagulation therapy is routinely initiated to prevent thrombus propagation or embolization (unless there is brain hemorrhage). Antiplatelet therapy may be equally efficacious, 10 and can be initiated upon suspicions of CAD and while confirmatory studies are in progress. The prognosis for extracranial dissections is generally good.

Cervical Epidural Hematoma Cervical (spinal) epidural hematoma is an uncommon but potentially catastrophic event that can lead to permanent neurological deficits and death from respiratory failure. It presents as sudden and severe local neck pain with rapid development of radicular pain at the corresponding dermatomes. Motor and sensory deficits follow within minutes to days.12,13 Bleeding can occur spontaneously or secondary to trauma, surgery, or coagulopathy (which itself may be pathological—eg, hemophilia or iatrogenic in origin).14,15 Untreated, progressive cord compression can lead to permanent neurological deficits and death from respiratory failure. In the patient with acute neurological deficits, immediate correction of coagulation issues is required before decompressive surgery.