Ninety percent of cases of Ludwig’s angina are odontogenic, often due to periapical abscesses. This condition may result secondary to any oral or parapharyngeal infection that spreads by continuity from the submandibular space into the contiguous sublingual and submental spaces. The potential for airway obstruction comes from elevation and displacement of the tongue, resulting in a mortality rate greater than 50% if untreated. Causative organisms mirror normal, polymicrobial oral flora and include Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Fusobacterium, and Bacteroides.38,23

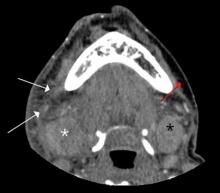

Diagnosis of Ludwig’s angina is primarily clinical. Neck pain and swelling, dental pain, dysphagia, malaise, and fever, along with a protruding or elevated tongue, are typical. Submandibular swelling, which is seen in 95% of patients, develops in advanced cases into an intense “woody” induration above the hyoid bone that portends the impending airway crisis.39 If the patient is sufficiently clinically stable and able to lie flat, definitive diagnosis can be made with a contrastenhanced, soft-tissue neck CT (Figure 4), which can also evaluate for a drainable abscess, soft-tissue gas, and mediastinal extension; this modality can also define the extent of soft-tissue swelling and airway patency.

Figure 4. Axial computed tomography scan of the upper neck demonstrates infiltration of the subcutaneous fat of the right submandibular region (white arrow) in a patient with Ludwig’s angina. Note the normal fat on the contralateral side (red arrow). There is also enlargement and edema of the right submandibular gland (white asterisk) as compared to the left (black asterisk).

Airway management is the primary consideration because of its potential for rapid deterioration. Traditional management has been aggressive and surgical, with the standard being early tracheostomy. More recent reports have encouraged more conservative management when possible.40 Impending or actual airway compromise, as manifest by significant trismus, inability to flex the neck without compromising the airway, inability to protrude the tongue, or actual resting dyspnea demand that a surgical airway be readied at bedside until fiber optic nasotracheal intubation is secured.

Antibiotics must be given early and include coverage for gram-positive, gramnegative, and anaerobic organisms. Intravenous metronidazole and penicillin (cefazolin or clindamycin if patient has an allergy to penicillin) are commonly prescribed.38,23 Although controversial, administration of IV dexamethasone (8 mg to 12 mg) and nebulized epinephrine (1:1000, 1 mL diluted to 5 mL with normal saline) to reduce edema has been advocated. 41

Lemierre’s Syndrome Lemierre’s syndrome, septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, was first described in 1936 by André Lemierre, who published a series of cases of previously healthy young adults in whom oropharyngeal infections were followed by “anaerobic postanginal septicaemias.”42 Most of these patients presented with sore throat (referred to as “angina” in “old skool” speak) and worsening pain and tenderness at the anterolateral neck, with pulmonary symptoms manifesting several days to 2 weeks later. The causative organism, Fusobacterium necrophorum, is a gram-negative anaerobe that is part of the normal commensal oropharyngeal flora. It invades the internal jugular (IJ) vein via the lateral pharyngeal space and releases a hemagglutinin that promotes thrombus formation in the IJ and, ultimately, metastatic septic emboli. These emboli typically invade the lungs and cause multiple nodular infiltrates and small pleural effusions. Unfortunately, as each case is unique, diagnosis is often delayed. Septic emboli can migrate to other sites and cause arthritis (hip, knee, shoulder, sacroiliac, and other joints), osteomyelitis, young adult with a history of recent sore throat and fever who subsequently developed neck pain and tenderness (with or without swelling) over the IJ, rigors, pulmonary infiltrates, and possibly other signs of septic emboli.

Figure 6. Sagittal T1-weighted fat-suppressed magnetic resonance image of the cervical spine obtained following administration of intravenous contrast reveals enhancement of the C5 and C6 vertebral bodies and increased signal in the intervening disc space. Abnormal enhancement is also noted in the C4-C5 disc. These findings are consistent with spondylodiskitis.

Doppler ultrasound or CT will show IJ thrombosis43 (Figure 5). Purulent discharge, if obtained, has a characteristic foul smell that has been likened to “limburger or overripe Camembert cheese.”44 Treatment is with high-dose IV penicillin and metronidazole or with clindamycin as single coverage. Heparin could potentially aid in dissemination of emboli, but it is used only when there is retrograde propagation of clot to the cavernous sinus.

With the routine antibiotic treatment of pharyngitis in the 1960s and 1970s, cases of Lemierre’s syndrome became so rare that it was referred to as the “forgotten disease.”45 Unfortunately, its incidence has increased over the past few years.43 It is unclear whether this rise is due to increasing antibiotic resistance or to an increasing resistance of clinicians to use antibiotics for “sore throats.”