The secondary medication options include sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, and insulin. Insulin therapy is the final medication step for all patients with DM who are willing and able to comply with daily injections and who have failed to meet goals through alternative agents.

Before using additional agents beyond metformin, the PCP or endocrinologist should discuss in detail factors such as side effects (ie, weight gain, risk of hypoglycemia), medication delivery (GLP-1 agonists and insulin require injections), and cost with the patient. It is generally advisable not to try to accomplish this medication adjustment in the ED without consultation with a PCP or endocrinologist.

Diagnosis

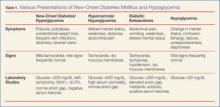

The clinical presentation of new-onset DM can range from the relatively benign (eg, polyuria, polydipsia, frequent skin infections) to the life-threatening (eg, diabetic ketoacidosis) (Table 1). The classic symptoms of hyperglycemia include polyuria, polydipsia, unexplained weight loss, easy fatigability, dizziness, and blurred vision. Any one of these symptoms should prompt consideration of DM in the differential diagnosis.

Four abnormal laboratory results comprise the ADA’s diagnostic criteria for DM6:

- HbA1c ≥6.5%;

- 8-hour fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL;

- 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥200 mg/dL (Patient is given 75 g sugar orally; then plasma glucose is drawn 2 hours later); and

- A random plasma glucose of ≥200 mg/dL in association with “classic symptoms” of DM, defined as polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss.

In the absence of an unequivocal indicator, such as the patient presenting in diabetic ketoacidosis, the formal diagnosis of DM should not be made unless at least 2 abnormal test results are obtained simultaneously (from a 2-hour OGTT test and an HbA1c panel, for example, or when the same test is repeated one month later and both test results indicate DM).

Limitations of Glucometers

When interpreting test results, keep in mind that the US Food and Drug Administration allows point-of-care (POC) glucometers to have an accuracy of +/- 20%. The POC glucometers measure whole-blood glucose rather than plasma glucose; generally the amount of glucose in plasma is about 10% to 15% higher than the amount in whole blood.7 Therefore, the formal diagnosis of DM relies on laboratory plasma glucose results; POC glucometer results may guide the EP in initiating a workup for DM but should not be among the diagnostic criteria.

HbA1c Testing

The HbA1c percentage represents the preceding 3-month average plasma glucose level. This is due to nonenzymatic glycosylation of Hb, a reaction driven by higher concentrations of circulating plasma glucose. The HbA1c can be falsely low in states of high red blood cell (RBC) turnover, such as ongoing blood loss or the RBC fragility seen in hemoglobinopathies. Patients who have had RBC transfusions in the preceding months will have inaccurate HbA1c test results as well.

Keeping these test characteristics in mind, the HbA1c test may be more useful than glucose-based testing strategies in diagnosing diabetes in the ED. Hyperglycemia can be observed in nondiabetic emergency patients undergoing a stress response, since gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis are normal hepatic stress responses to circulating epinephrine and cortisol. Unless a patient is on chronic steroids, the HbA1c is not similarly affected.

A recent study of ED patients using HbA1c as the sole screening modality found that test characteristics for ED patients were similar to those for patients in typical outpatient settings. HbA1c of 6.5 or greater yielded a sensitivity of 54% and a specificity of 96% in diagnosing diabetes.8 The availability of test results at the time of the emergency visit depends upon the individual hospital laboratory, but most labs run the test itself in less than an hour. Emergency physicians working in hospitals that perform the test will often have the test results prior to patient discharge.

Inpatient Management

Managing a patient with newly diagnosed DM that requires admission to the hospital is different from managing a patient who can be treated as an outpatient. The ADA-recommended treatment regimen for DM in the inpatient setting focuses on the use of insulin. While type 1 DM, by definition, requires insulin treatment, many patients with type 2 DM are treated with oral agents only as outpatients. However, because of complications associated with the use of oral agents in low renal perfusion states (such as during surgery, during IV contrast-enhanced studies, or when the admitting condition causes shock), the ADA generally does not prefer oral agents for inpatient glycemic control. Metformin particularly should not be used in the inpatient setting, due to increased risk of lactic acidosis.