Background

Emergency physicians and other clinicians frequently encounter patients presenting with soft-tissue complaints. Oftentimes, there is diagnostic uncertainty as to whether a patient has cellulitis, an abscess, or both. A prospective observational study by Tayal et al,1 demonstrated that bedside ultrasound assisted in identifying and differentiating abscess versus cellulitis, altering management in half of the patients.

Anatomy

The soft-tissue layers that can be visualized by ultrasound include the epidermis/dermis, subcutaneous layer, fascia, muscle, and bone (Figure 1).The epidermis and dermis are indistinguishable by ultrasound, and appear as a single thin bright layer. Below the epidermis and dermis, the subcutaneous layer appears as dark layer, which represents fat and bright connective tissue layer. Deep to that is the fascia, which is a linear bright layer. Below the fascia, muscle fascicles can be seen, which appear as bright striations in a fibrillar pattern.

Preparation and Technique

Soft-tissue ultrasound should be performed using a high frequency linear probe (5-12 MHz or greater) as this allows for higher resolution scanning of superficial structures. For deeper structures, a curvilinear probe can be used instead; however, these images will have a lower resolution.For practical and infection-control purposes, a tegaderm barrier dressing is recommended for covering the end of the probe (Figure 2). Structures should be viewed in at least two planes (ie, longitudinal and short axis).

Cellulitis

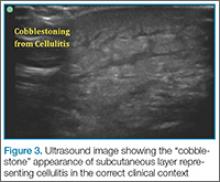

Cellulitis is a common skin and soft-tissue condition, and one that can be visualized quite easily on ultrasound, though its appearance does vary to some degree depending on severity. Early cellulitis can be subtle with increased echogenicity of the skin/subcutaneous fat layers. As cellulitis progresses, it has the more characteristic appearance of “cobblestones,” areas of hyperechoic islands of fat lobules separated by hypoechoic fluid (Figure 3). This finding, however, is not specific to cellulitis alone, but can be seen in other conditions that cause interstitial swelling, such as congestive heart failure and peripheral edema.

Abscess

Abscess on ultrasound can be visualized as a hypoechoic collection in the subcutaneous space (Figure 4). It often contains material of mixed echogenicity, and there may be internal septations in the abscess. Simple cysts have the appearance of anechoic fluid collection. On ultrasound, a posterior acoustic enhancement artifact may be seen in both abscesses and cysts.Putting a little downward pressure with the linear transducer over the abscess can produce swirling or movement within the abscess cavity, and has been informally coined “pustalsis” (Figure 5).

Lymph Nodes

It is sometimes important and useful to distinguish between an abscess and an enlarged lymph node, particularly in the axilla and groin region. Ultrasound can also assist in differentiating between these two conditions. Lymph nodes have an echogenic hilum or center with the periphery of the lymph node appearing darker. (Figure 6)If color flow is placed on the area, blood flow into the node can be seen. Ultrasound can avoid unnecessary incision and drainage procedure in a patient with lymphadenopathy.

Conclusion

Bedside ultrasound is a useful and easily accessible tool to confirm the diagnosis and facilitate treatment in patients with soft-tissue complaints, including cellulitis, abscess, and lymphadenopathy. This modality is especially helpful in identifying vascular structures in areas such as the axilla or groin when incision and drainage are indicated, and can also help avoid mistaking an abdominal wall hernia for an abscess.

Dr Meer is an assistant professor and director of emergency ultrasound, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Taylor is an assistant professor and director of postgraduate medical education, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Beck is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.