Answer

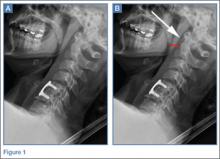

The lateral view of the cervical spine demonstrated soft tissue swelling in the upper prevertebral region (red arrowheads, Figure 1b). (The soft tissues at this level in an adult normally measure less than 3 mm between the airway and the vertebral body.) The radiograph also showed an area of calcification within the prevertebral soft tissues (white arrow, Figure 1b).

The patient denied fevers, chills, dysphagia, visual changes, and nasal congestion. Physical examination demonstrated tenderness to palpation of the posterior neck, but there was no evidence of palpable mass or lymphadenopathy. Neck extension and lateral movement to the left were severely limited due to pain; neck flexion and lateral movement range of motion to the right were mildly decreased due to pain. The physical examination was otherwise normal.

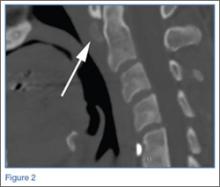

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck was performed to further evaluate the soft tissue swelling and confirm the calcification (white arrow, Figure 2). The CT localized the abnormality to the expected location of the longus colli tendon. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine with and without contrast was performed to directly visualize the tendon/effusion and to exclude prevertebral abscess. The MRI showed abnormally increased fluid signal about the longus colli tendon on Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) images (white arrows, Figure 3a). This fluid extended in all directions from the calcifications and lacked a defined enhancing wall on postcontrast images (white arrows, Figure 3b), suggesting that the fluid reflected reactive effusion rather than soft tissue abscess. A flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopic examination was normal, including the lack of bulging of the retropharyngeal wall. The constellation of these imaging and clinical findings was consistent with the diagnosis of longus colli (prevertebral) calcific tendinitis. Longus colli (prevertebral) calcific tendinitis results from calcium hydroxyapatite deposition within the tendon. While the bilateral longus colli muscles extend from the atlas to the upper thoracic vertebral level, calcium hydroxyapatite crystals typically deposit at the C1-C2 level1,2 (as seen in this case). Associated inflammation of the tendon can result in prevertebral fluid that may be confused for retropharyngeal abscess, particularly given the associated neck pain and stiffness, dysphagia, odynophagia, and possible mild leukocytosis and/or mild C-reactive protein elevation. 1 However, imaging in this case confirmed that the prevertebral fluid extended from the calcium deposits in the tendon and excluded the presence of a rim-enhancing abscess collection. Knowledge of this clinical entity is important given its similar clinical presentation to other conditions with differing treatment strategies (eg, retropharyngeal abscess, meningitis).3Longus colli (prevertebral) calcific tendinitis is a self-limiting condition that typically lasts 1 to 3 weeks, though it can be very painful during the acute phase.1,2 Treatment is typically conservative, and the patient in this case received a course of oral corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to help alleviate the associated inflammation.

Dr Bartolotta is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Baradaran is a resident in the department of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center; and associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.