High serum insulin and leptin levels were significantly associated with Barrett’s esophagus, according to authors of a meta-analysis of nine observational studies published in the December issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Compared with population controls, patients with Barrett’s esophagus were twice as likely to have high serum leptin levels, and were 1.74 times as likely to have hyperinsulinemia, said Dr. Apoorva Chandar of Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland) and his associates.

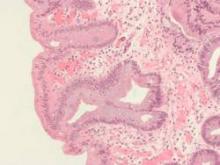

Central obesity was known to increase the risk of esophageal inflammation, metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.009]), but this meta-analysis helped pinpoint the hormones that might mediate the relationship, the investigators said. However, the link between obesity and Barrett’s esophagus “is likely complex,” meriting additional longitudinal analyses, they added.

Metabolically active fat produces leptin and other adipokines. Elevated serum leptin has anti-apoptotic and angiogenic effects and also is a marker for insulin resistance, the researchers noted. “Several observational studies have examined the association of serum adipokines and insulin with Barrett’s esophagus, but evidence regarding this association remains inconclusive,” they said. Therefore, they reviewed observational studies published through April 2015 that examined relationships between Barrett’s esophagus, adipokines, and insulin. The studies included 10 separate cohorts of 1,432 patients with Barrett’s esophagus and 3,550 controls, enabling the researchers to estimate summary adjusted odds ratios (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.06.041]).

Compared with population controls, patients with Barrett’s esophagus were twice as likely to have high serum leptin levels (adjusted OR, 2.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.31-3.78) and 1.74 times as likely to have elevated serum insulin levels (95% CI, 1.14 to 2.65). Total serum adiponectin was not linked to risk of Barrett’s esophagus, but increased serum levels of high molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin were (aOR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.16-2.63), and one study reported an inverse correlation between levels of low molecular weight leptin and Barrett’s esophagus risk. Low molecular weight adiponectin has anti-inflammatory effects, while HMW adiponectin is proinflammatory, the researchers noted.

“It is simplistic to assume that the effects of obesity on the development of Barrett’s esophagus are mediated by one single adipokine,” the researchers said. “Leptin and adiponectin seem to crosstalk, and both of these adipokines also affect insulin-signaling pathways.” Obesity is a chronic inflammatory state characterized by increases in other circulating cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor–alpha, they noted. Their findings do not solely implicate leptin among the adipokines, but show that it “might be an important contributor, and support further studies on the effects of leptin on the leptin receptor in the proliferation of Barrett’s epithelium.” They also noted that although women have higher leptin levels than men, men are at much greater risk of Barrett’s esophagus, which their review could not explain. Studies to date are “not adequate” to assess gender-specific relationships between insulin, adipokines, and Barrett’s esophagus, they said.

Other evidence has linked insulin to Barrett’s esophagus, according to the researchers. Insulin and related signaling pathways are upregulated in tissue specimens of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s esophagus is more likely to progress to esophageal adenocarcinoma in the setting of insulin resistance, they noted. “Given that recent studies have shown an association between Barrett’s esophagus and measures of central obesity and diabetes mellitus type 2, it is conceivable that hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance, which are known consequences of central obesity, are associated with Barrett’s esophagus pathogenesis,” they said.

However, their study did not link hyperinsulinemia to Barrett’s esophagus among subjects with GERD, possibly because of confounding or overmatching, they noted. More rigorous studies would be needed to fairly evaluate any relationship between insulin resistance and risk of Barrett’s esophagus, they concluded.

The National Cancer Institute funded the study. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.