Be vigilant for anxiety, depression—even when COPD is mild

One reason comorbid GAD or MDD may be overlooked and underdiagnosed is that the symptoms can overlap those of COPD. In cases where suspicion of GAD or MDD is warranted, providers must keep separate the diagnostic inquiries for COPD and these comorbidities.6

Somatic symptoms of anxiety, such as hyperventilation, shortness of breath, and sweating, may easily be attributed to pulmonary disease instead of a psychological disorder. Differentiating the 2 processes becomes more difficult with patients younger than 60 years, as they are more likely to experience symptoms of GAD or MDD than older patients, regardless of COPD severity.15 Therefore, when assessing COPD patients, physicians need to be more vigilant for anxiety and depression, even in the mildest cases.14

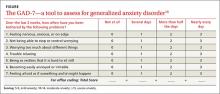

Several methods exist for assessing anxiety and depression, including the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener 7 (GAD-7) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 2 or 9.16 All PHQ and GAD-7 screeners and translations are downloadable from www.phqscreeners.com/select-screener and permission is not required to reproduce, translate, display, or distribute them (FIGURE).16 Other anxiety and depression screening instruments are also available.

No one method has been shown to be most effective for rapid screening, and the physician’s comfort level or familiarity with a particular assessment tool may guide selection. One advantage of short screening instruments is that they can be incorporated into electronic health records for easy use across continuity visits. Although routine screening for these mental comorbidities takes slightly more time—especially in high-volume family practice clinics—it needs to become standard practice to protect patients’ quality of life.

Managing psychiatric conditions in COPD

Treatment for GAD and MDD in COPD is often suboptimal and may diminish a patient’s quality of life. In one study, COPD patients with a mental illness were 46% less likely than those with COPD alone to receive medications such as short- or long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids.17 Therapy for both the physiologic abnormalities and mental disturbances should be initiated promptly to maintain an acceptable state of health.

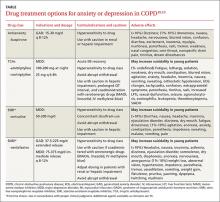

Pharmacotherapy. Reluctance to give traditional psychiatric medications to COPD patients contributes to the under-treatment of mental comorbidities. While benzodiazepines are generally not recommended—especially in severe COPD cases due to their sedative effect on respiratory drive—alternatives such as buspirone, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been shown to effectively reduce GAD, MDD, and dyspnea in these patients5,14(TABLE18,19).

Non-pharmacotherapy approaches. Having patients apply behavioral-modification principles to their own behavior20 has been proposed as a standard of care in the treatment of COPD.21 A recent systematic review found that self-management (behavior change) interventions in patients with COPD improved health-related quality of life, reduced hospital admissions, and helped alleviate dyspnea.22 While that review could not make clear recommendations regarding the most effective form and content of self-management in COPD,22 patient engagement and motivation in creating treatment goals are considered critical ingredients for effective self-management.21

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based behavioral approach designed for patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change.23 MI works by supporting a patient’s autonomy and by activating his/her own internal motivation for change or adherence to treatment. In MI, the physician’s involvement with the patient relies on collaboration, evocation, and autonomy, rather than confrontation, education, and authority. MI involves exploration more than exhortation, and support rather than persuasion or argument. The overall goal of MI is to increase intrinsic motivation so that change arises from within and serves the patient’s goals and values.23

Benzo, et al, provide a very detailed description of a self-management process that includes MI.21 Their protocol proved to be feasible in severe COPD and helped increase patient engagement and commitment to self-management.21 This finding and similar evidence of MI’s effectiveness in a variety of other health conditions suggest that pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy can be delivered in combination with an MI approach.

Self-management depends on a patient’s readiness to implement behavioral changes. Patients engaged in unhealthy behavior may be reluctant to change at a particular time, so the physician may focus efforts on such behaviors as self-monitoring or examining values that may lead to future behavior change.

For example, a patient may not want to stop smoking, but the physician’s willingness to ask about smoking in subsequent visits may catch the patient at a time when motivation has changed—eg, perhaps there is a new child in the home, prompting a recognition that smoking is now inconsistent with one’s values and can be resolved with smoking cessation. Awareness of an individual’s baseline behavior and readiness to change assists physicians and other health professionals in tailoring interventions for the most favorable outcome.