The FP suspected that this patient had measles, but since it has a low prevalence in the United States, he confirmed the diagnosis with a specific serum immunoglobulin M antibody test. Measles is a highly communicable, acute, viral illness that is still one of the most serious infectious diseases in human history. Until the introduction of the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, it was responsible for millions of deaths worldwide annually. Eradication of measles is possible, but the ease of transmission and the low percentage of nonimmunized population that is required for disease survival have made eradication extremely difficult.

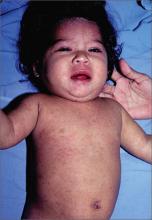

The classic measles rash is maculopapular and blanches under pressure. The rash begins on the face and spreads centrifugally to involve the neck, trunk, and, finally, the extremities. This cranial-to-caudal rash progression is characteristic of measles. The cough may persist for up to 2 weeks. Fever persisting beyond the third day of rash suggests a measles-associated complication.

Postinfectious encephalomyelitis can also occur. Postinfectious encephalomyelitis is a demyelinating disease that presents during the recovery phase, and is thought to be caused by a postinfectious autoimmune response.

The treatment of measles is mostly supportive and patients will need to stay away from other individuals—particularly unimmunized children and adults, pregnant women, and immunocompromised people—until at least 4 days after rash onset. Suspected cases of measles should be reported immediately to the local or state department of health.

In this case, the child showed no evidence of pneumonia, neurological symptoms, or dehydration, so hospitalization was not needed. Fortunately, the mother and father had both been vaccinated as children and this was their only child. Antipyretics and fluids were recommended. The parents were told to avoid giving the child aspirin to prevent Reye’s syndrome.

The FP maintained contact with the family over the phone and the symptoms began resolving within a few days. The FP also reported the case to the local health department.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Eric Kraus. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Baudoin L. Measles. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY:McGraw-Hill;2013:723-727.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com