For the first time, the American Academy of Pediatrics is offering guidance on managing menstruation and sexuality education in adolescents with disabilities.

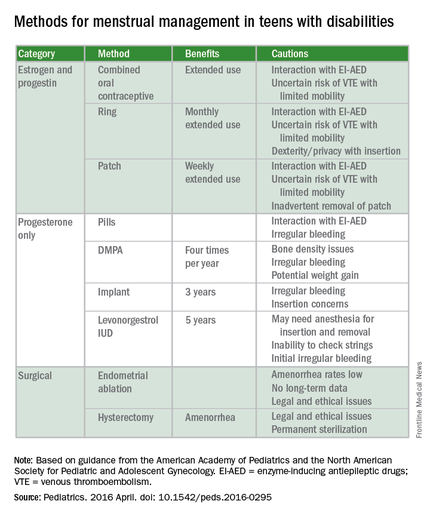

Written jointly with the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, the clinical report offers guidance on options for menstrual management, sexual education and expression, and protection from sexual abuse. The report gives guidance regarding the care of adolescents with physical and/or intellectual abilities, but not for those with psychiatric illnesses (Pediatrics. 2016 April. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0295).

“Taking care of teens with disabilities and figuring out what to do with menstrual management has been all over the map,” Dr. Cora Collette Breuner, chair of the AAP’s committee on adolescence, said in an interview. “So, we tried to clarify it and help clinicians know what to do and when.”

A particular concern for the two groups was the threat of adverse events. “We wanted to cover what’s safe and what’s not in menstruation management, especially around bone health and thromboembolic events,” said Dr. Breuner, a professor of pediatrics and adolescent medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Some of the information will not surprise clinicians, but there are some data that will perhaps come as news, said Dr. Breuner, including the recommendation that long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as the levonorgestrel intrauterine device or the progesterone implant rod should be considered first-line management therapies. “We point out that a number of studies show that these are safe.”

The report emphasizes offering anticipatory guidance before menses begins, noting that most teens with disabilities mature at the same rate as teens without disabilities. The report does not recommend premenarchal suppression in these patients, because doing so can interfere with normal bone growth. Such suppression also prevents patients and their families and caregivers from discovering that coping with the onset of menses is perhaps not as difficult as they might fear, the report states.

Although combined oral contraceptives are not contraindicated in teens with mobility issues, to guard against the threat of thromboembolic events in teens who use wheelchairs, the report recommends taking a thorough family history to rule out inherited thrombophilia. Otherwise, the recommendation is to prescribe the lowest-dose estrogen with a first- or second-generation progestin, as these are associated with lower rates of venous thrombotic events.

The guidance states that if cycles are creating difficulties in the patient’s life, “as determined by health care providers, patients, and families,” then menstrual management is appropriate. Even though it may take up to 3 years before a menstrual cycle becomes regular, the report cites irregularities caused by certain medications can be reason enough for menstrual management. Specific drugs noted include those affecting the dopaminergic system, valproic acid, and medications that elevate prolactin. Teens with obesity, seizure disorders, and polycystic ovary syndrome also can experience higher rates of irregularity.

The report also warns against the assumption that teens with disabilities are asexual or uninterested in sex. When appropriate, they should be offered the same confidential conversations about sexuality as are recommended for all teenagers by the AAP and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Teenagers with physical disabilities are just as likely to be sexually active as their peers and have a higher incidence of sexual abuse,” the report states. It is typically when a patient is cognitively impaired that consent to confidential services may require “discussion about legal guardianship or medical power of attorney status for families,” according to the report.

The report’s comprehensive review of four main menstrual management techniques – estrogen-containing, progestin-only, nonhormonal methods, and surgical requests and options – begins with the caveat that regardless of the method used, the threat of abuse or sexually transmitted infections remain. When a patient’s family or caregivers request suppression of menarche in a patient, stating fears of abuse or pregnancy, further investigation into the patient’s circumstances is warranted, the report states.

“It’s always worth reminding physicians that in this cohort, endometrial ablation can have legal implications, and it’s not recommended in this age group,” Dr. Breuner said.

On average, 1.5 hormonal methods are tried before achieving management goals, according to the report. Data cited in the study showed that at 42%, oral contraception is the preferred method of menstrual suppression, followed by the patch at 20%. Expectant management was third at 15%, followed by DMPA (depot medroxyprogesterone acetate) at 12%. The least utilized method was the levonorgestrel intrauterine device at 3%. No data were provided for the implantable contraceptive rod.

The clinical report is a companion document to another AAP clinical report, “Sexuality of Children and Adolescents with Developmental Disabilities” (Pediatrics. 2006. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1115).