Dietary phosphate restriction is often challenging for patients, in part, because phosphorous content is not always included on food labels in the United States.9 Phosphorus is highly absorbed from additives in processed food (approaching 100% absorption), less absorbed from animal sources such as meat and dairy products (40%-60%), and is the least absorbed from plant sources such as beans and nuts (20%-40%).10 Advise patients to avoid fast food, processed foods, cheese, frozen meals, colas, and certain ready-to-eat cereals and prepared meats, as these products may have additives from which phosphorus is readily absorbed.11 A patient-friendly list of high-phosphorus foods, as well as other dietary advice and recipes, can be found on the National Kidney Foundation Web site at https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/phosphorus. Tables listing the phosphorus content of common foods are also available in the literature and online.11,12 Keep in mind that not all resources take into account phosphate bioavailability. Dietician referral may be helpful to assure that patients maintain adequate protein intake while restricting dietary phosphate.

Phosphate binders are recommended by the KDIGO guidelines for use in patients with kidney disease and hyperphosphatemia.6 Most of the data to support the use of phosphate binders was gleaned from the dialysis population. The use of phosphate binders in non-dialyzed patients with CKD has both proponents and opponents, with literature supporting both positions.13,14 A recent KDIGO conference on controversies in CKD-MBD identified this as an area that should be evaluated further for the next guideline update.15

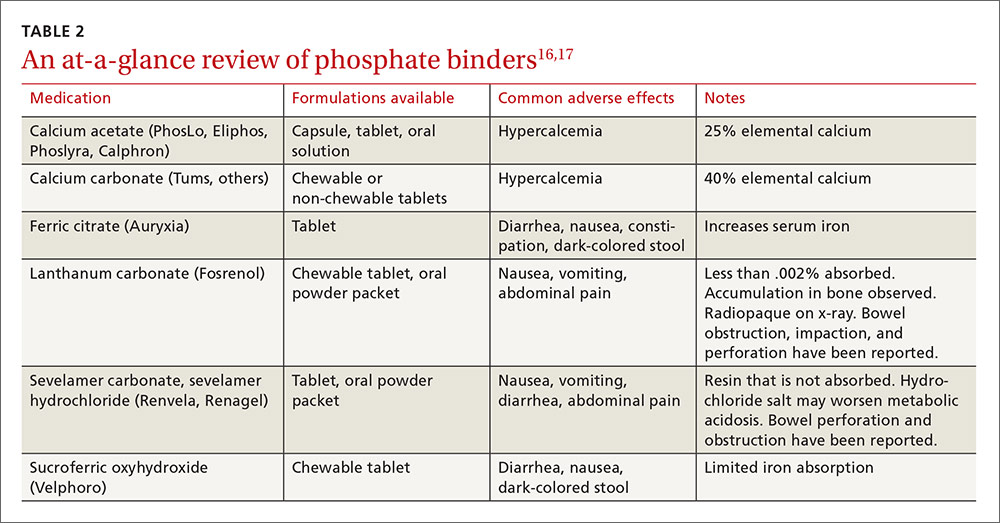

Phosphate binders—which bind the phosphorus in food to prevent absorption—should be taken with meals or high-phosphorus snacks. Products and formulations of commonly used phosphate binders are shown in TABLE 2.16,17 Taste, formulation, adverse effects, pill burden, and cost are issues to discuss with patients when initiating or adjusting phosphate binder therapy. It’s estimated that more than half of all patients receiving dialysis do not adhere to their prescribed phosphate binder regimen, highlighting the need to assess adherence before adjusting dose and to involve the patient in the decision-making process to select a phosphate binder product.18

Avoid calcium-based binders? The risk of hypercalcemia and the potentially increased risk of vascular calcifications with calcium-based binders have led some nephrologists to favor non-calcium-based products. Two recent meta-analyses found a reduced risk of all-cause mortality with the non-calcium-based binders sevelamer or lanthanum as compared to calcium-based binders.19,20 Current KDIGO guidelines were published prior to these meta-analyses and do not recommend one phosphate binder over another. They do, however, recommend restricting the dose of calcium-based binders in the setting of persistent or recurrent hypercalcemia, known vascular calcification, or low PTH levels.6

Secondary hyperparathyroidism

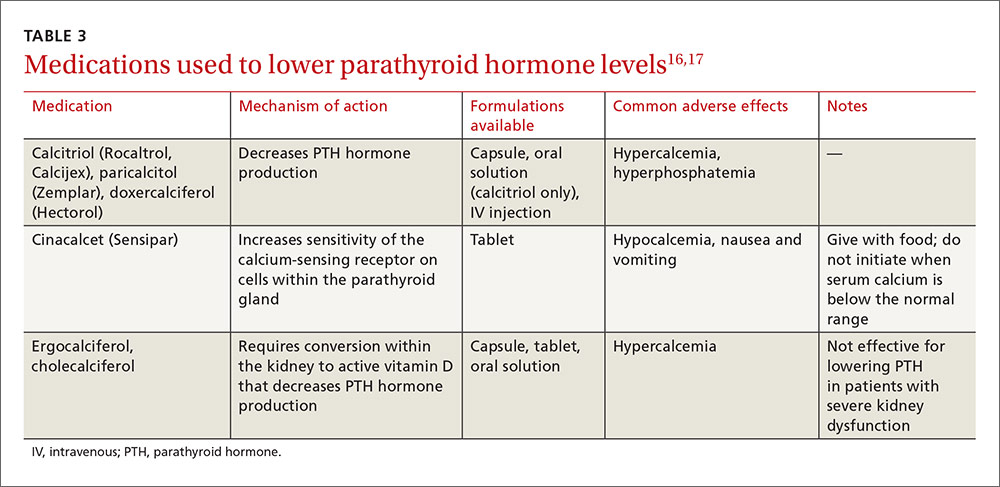

Due to a lack of data, the goal PTH level in patients not receiving dialysis is unknown.6 A reasonable approach in non-dialyzed patients, however, is to correct 25-OH vitamin D (25[OH]D) deficiency, elevations in serum phosphate, and hypocalcemia when the level of intact PTH (iPTH) exceeds the normal range for the assay because correcting these derangements may result in a decline in iPTH.6,21 If this approach fails and PTH levels continue to rise, use of calcitriol or vitamin D analogues is recommended.6 Characteristics of medications used to treat SHPT are presented in TABLE 3.16,17

In dialysis patients, the target iPTH range suggested by KDIGO is 2 to 9 times the upper limit of normal for the assay.6 Elevated PTH levels in the dialysis population may be managed with activated vitamin D and/or cinacalcet.

Native vitamin D (ergocalciferol, cholecalciferol) and activated vitamin D analogs (calcitriol, doxercalciferol, paricalcitol). Native vitamin D products are recommended for non-dialyzed patients with CKD to correct vitamin D deficiencies. Although many approaches may be used clinically to replenish low vitamin D stores, one reasonable recommendation in patients with a 25(OH)D level <30 ng/mL is to prescribe ergocalciferol 50,000 units/week for 8 weeks and then to repeat the serum 25-OH vitamin D test. If the level is still <30 ng/mL, a second 8-week course of weekly ergocalciferol 50,000 IU may be administered.21

Following repletion with ergocalciferol, maintenance doses of cholecalciferol (1000-2000 IU/d) or ergocalciferol (50,000 IU/-month) may be initiated.21 Discontinue native vitamin D in patients who develop hypercalcemia.