Nasal obstruction is one of the most common reasons that patients visit their primary care providers.1,2 Often described by patients as nasal congestion or the inability to adequately breathe out of one or both nostrils during the day and/or night, nasal obstruction commonly interferes with a patient’s ability to eat, sleep, and function, thereby significantly impacting quality of life. Overlapping presentations can make discerning the exact cause of nasal obstruction difficult.

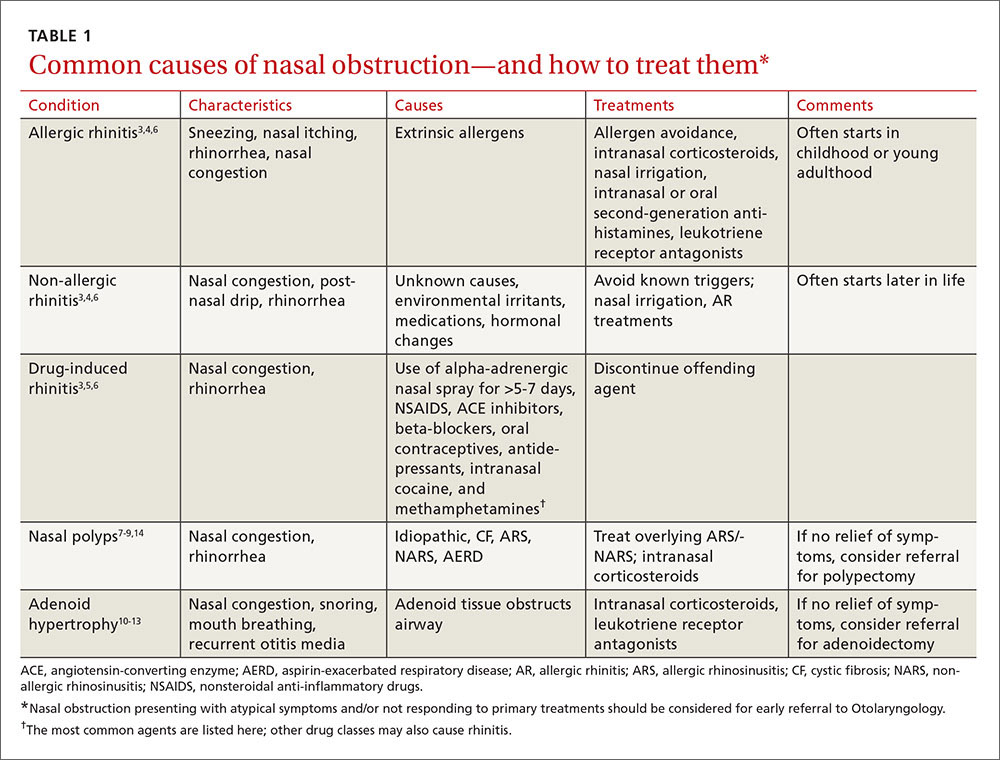

To improve diagnosis and treatment, we review here the evidence-based recommendations for the most common causes of nasal obstruction: rhinitis, rhinosinusitis (RS), drug-induced nasal obstruction, and mechanical/structural abnormalities (TABLE 13-14).

Rhinitis/rhinosinusitis: It all begins with inflammation

Sneezing, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, and nasal itching are complaints that signal rhinitis, which affects 30 to 60 million people in the United States annually.3 Rhinitis can be allergic, non-allergic, infectious, hormonal, or occupational in nature. All forms of rhinitis share inflammation as the cause of the nasal obstruction. The most common form is allergic rhinitis (AR), which includes seasonal AR and perennial AR. Seasonal AR is typically caused by outdoor allergens and waxes and wanes with pollen seasons. Perennial AR is caused mostly by indoor allergens, such as dust mites, molds, cockroaches, and pet dander; it persists all or most of the year.6 Causes of non-allergic rhinitis (NAR) include environmental irritants such as cigarette smoke, perfume, and car exhaust; medications; and hormonal changes,6 but most causes of NAR are unknown.3,6

While AR can begin at any age, most people develop symptoms in childhood or as young adults, whereas NAR tends to begin later in life. Nasal itching can help to distinguish AR from NAR. NAR symptoms tend to be perennial and include postnasal drainage. If symptoms persist longer than 12 weeks despite treatment, the condition becomes known as chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS).

Treatment of rhinitis: Tiered and often continuous

Treatment of AR and NAR is similar and multitiered beginning with the avoidance of irritants and/or allergens whenever possible, moving on to pharmacotherapy, and, at least for AR, ending with allergen immunotherapy. Treatment is often an ongoing process and typically requires continuous therapy as opposed to treatment on an as-needed basis.3 It is unnecessary to perform allergy testing before making a presumed diagnosis of NAR and starting treatment.6

Intranasal corticosteroids. Currently, intranasal glucocorticosteroids (INGCs) are the most effective monotherapy for AR and NAR and have few adverse effects when used at prescribed doses.3,4 For mild to intermittent symptoms, begin with the maximum dosage of an INGC for the patient’s age and proceed with incremental reductions to identify the lowest effective dose.3 If INGCs alone are ineffective, studies have shown that the addition of an intranasal second-generation antihistamine can be of some benefit.3,4 In fact, an INGC and an intranasal antihistamine—along with saline nasal irrigation—is recommended for both AR and NAR resistant to single therapy.3,6,15 If intranasal antihistamines are not an option, oral therapy can be initiated.

Start with second-generation antihistamines and consider LRAs. For oral therapy, start with second-generation antihistamines (loratadine, cetirizine, fexofenadine). First-generation antihistamines (diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, chlorpheniramine), although widely available at relatively low cost, can cause several significant adverse effects including sedation, impaired cognitive function, and agitation in children.3,4 Because second-generation antihistamines have fewer adverse effects, they are recommended as first-line therapy when oral antihistamine therapy is desired, such as for nasal congestion, sneezing, and itchy, watery eyes.

Of note: A 2014 meta-analysis found that a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LRA) (montelukast) had efficacy similar to oral antihistamines for symptom relief in AR, and that LRAs may be better suited to nighttime symptoms (difficulty falling asleep, nighttime awakenings, congestion on awakening), while antihistamines may provide better relief of daytime symptoms (pruritus, rhinorrhea, sneezing).16 Although further head-to-head, double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to confirm the results and investigate possible gender differences in symptom response, consider an LRA for first-line therapy in patients with AR who have predominantly nighttime symptoms.

What about pregnant women and the elderly?

It is important to consider teratogenicity when selecting medications for pregnant patients, especially during the first trimester.3 Nasal cromolyn has the most reassuring safety profile in pregnancy. Cetirizine, chlorpheniramine, loratadine, diphenhydramine, and tripelennamine may be used in pregnancy. The US Food and Drug Administration considers them to have a low risk of fetal harm, based on human data, whereas it views many other antihistamines as probably safe, based on limited or no human data. Most INGCs are not expected to cause fetal harm, but limited human data are available. Avoid prescribing oral decongestants to women who are in the first trimester of pregnancy due to the risk of gastroschisis in newborns.17