NEW ORLEANS – Women who experience peripartum cardiomyopathy or any of a variety of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are at sharply increased risk of acute MI, stroke, or new-onset heart failure beginning within just a few years, Rima Arnaout, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Our study supports the idea that women who have cardiovascular complications in pregnancy really need to be monitored closely for potential primary prevention of cardiovascular events,” said Dr. Arnaout of the University of California, San Francisco.

At a session devoted to “big data” studies in cardiovascular medicine, she presented one of the biggest: a retrospective cohort study of 1.66 million pregnancies during 2005-2009 in California women without any history of congenital or valvular heart disease or prepregnancy cardiovascular events. The California database was created as part of the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s comprehensive Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, which included more than 95% of the state’s hospitals. Women who experienced an MI or a stroke, or who were diagnosed with heart failure, during a median of 2.7 years and a maximum of 6 years of follow-up post pregnancy were identified via ICD-9 codes.

There were 111,202 cases of various forms of hypertension in pregnancy, for a 6.9% incidence. Peripartum cardiomyopathy was diagnosed in 562 women, for a rate of 3.5 cases per 10,000 pregnancies.

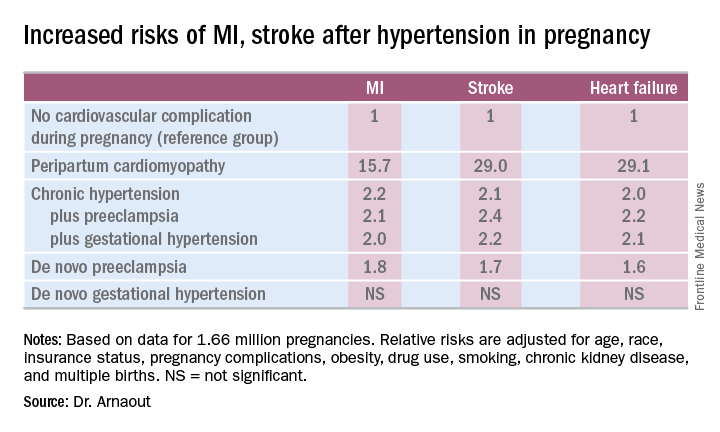

“We found that peripartum cardiomyopathy is associated not just with heart failure – I think that was already known – but with MI and stroke as well,” she said.Indeed, in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for numerous potential confounders, peripartum cardiomyopathy was associated with a 16-fold increased risk of acute MI during the relatively short follow-up period, as well as 29-fold increased risks of stroke and heart failure, compared with women with no cardiovascular issues during their pregnancy.

Chronic hypertension, regardless of whether it occurred alone or in combination with preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, was associated with roughly a twofold increased risk of each of the three study outcomes, compared with women who didn’t experience a cardiovascular complication during pregnancy. De novo preeclampsia was also associated with roughly a twofold increased risk of later MI, heart failure, or stroke.

The only form of hypertension in pregnancy that wasn’t associated with a subsequent significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events was de novo gestational hypertension.

Audience member David C. Goff Jr., MD, head of the division of cardiovascular sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md., rose to compliment Dr. Arnaout: “Great work and really important.”

He said that her findings are consistent with the notion that pregnancy constitutes a sort of early-life cardiovascular stress test. He said he wondered, however, just how comfortable Dr. Arnaout is in stating that gestational diabetes isn’t associated with increased subsequent cardiovascular risk, given the relatively short follow-up to date in this population of women who still remain several decades away from the age when cardiovascular event rates really start to climb.

“I completely agree with you,” she replied, noting that other investigators utilizing a different registry have reported an increased longer-term risk for women with gestational diabetes.

Dr. Arnaout said she and her coinvestigators plan to continue to follow the women who experienced peripartum cardiomyopathy or hypertension in pregnancy longer term. They’re also in the process of breaking down the data to look at the risks associated with specific subtypes of MI, stroke, and heart failure.

Dr. Arnaout reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the American Heart Association and the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation.