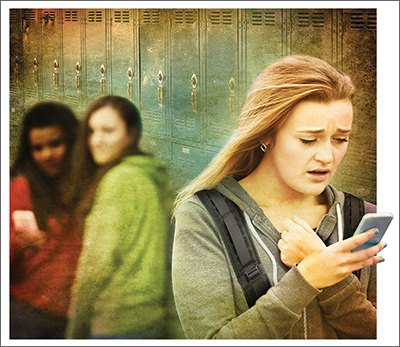

CASE › Stacey, a 12-year-old girl with mild persistent asthma, presents to her family physician (FP) with her mother for her annual well visit. Stacey reports no complaints, but has visited twice recently for acute exacerbations of her asthma, which had previously been well-controlled. When reviewing her social history, Stacey reports that she started her second year of middle school 3 months ago. When asked if she enjoys school, Stacey looks down and says, “School is fine.” Her mother quickly adds that Stacey has quit the school cheerleading team—much to the coach’s dismay—and is having difficulty in her math class, a class in which she normally excels. Stacey appears embarrassed that her mother has brought these things up. Her mother says that at the beginning of the year, 2 girls began picking on Stacey, calling her names and making fun of her on social media and in front of other students.

For many years, bullying was trivialized. Some viewed it as a universal childhood experience; others considered it a rite of passage.1,2 It was not examined as a public health issue until the 1970s. In fact, no legislation addressing bullying or “peer abuse” existed in the United States until the mass shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo, in 1999. Within 3 years of the Columbine tragedy, the number of state laws that mentioned bullying went from zero to 15; within 10 years of Columbine, 41 states had laws addressing bullying,1 and by 2015, every state, the District of Columbia, and some territories had a bullying law in place.3

As research and advocacy regarding bullying has grown, its impact on the health of children, adolescents, and even adults has become more apparent. In a 2001 study of school-associated violent deaths in the United States between 1994 and 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that among students, homicide perpetrators were more than twice as likely as homicide victims to have been bullied by peers.4 Given that homicide is the third leading cause of death in people ages 15 to 24,5 past exposure to bullying may be a significant contributing factor to mortality in this age group.4

In addition to a correlation with homicidal behavior, those involved in bullying—whether as the bully or victim—are at risk for a wide range of symptoms, conditions, and problems including poor psychosocial adjustment, depression, anxiety, suicide (the second leading cause of death in the 10-14 and 15-24 age groups5), academic decline, psychosomatic manifestations, fighting, alcohol use, smoking, and difficulty with the management of chronic diseases.6-10 Not only does being a victim of bullying have a direct impact on a child’s current mental and physical well-being, but it can have lasting psychological and behavioral effects that can follow children well into adulthood.7 The significant impact of bullying on individuals and society as a whole mandates a multifaceted approach that begins in your exam room. What follows is practical advice on screening, counseling, and working with schools and the community at large to curb the bullying epidemic.

Clarifying the problem: The CDC’s definition

Recognizing that varying definitions of bullying were being used in research studies that looked at violent or aggressive behaviors in youth, the CDC published a consensus statement in 2014 that proposed the following definition for bullying:11 any unwanted aggressive behavior by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. This expanded on an earlier definition by Olweus12,13 that also identified a longitudinal nature and power imbalance as key features.

Types of bullying. Direct bullying entails blatant attacks on a targeted young person, while indirect bullying involves communication with others about the targeted individual (eg, spreading harmful rumors). Bullying may be physical, verbal, or relational (eg, excluding someone from their usual social circle, denying friendship, the silent treatment, writing mean letters, eye rolling, etc.) and may involve damage to property. Boys tend toward more direct bullying behaviors, while girls more often engage in indirect bullying, which may be more challenging for both adults and other students to recognize.12,13 With increased use of technology and social media by adolescents, cyberbullying has become increasingly more prevalent, with its effects on adolescent health and academics being every bit as profound as those of traditional bullying.14

About 1 in 4/5 students suffer. The prevalence of bullying ranges by country and culture. The vast majority of early bullying research was conducted in Norway, which found that approximately 15% of students in elementary and secondary schools were involved in bullying in some capacity.12 In a study involving over 200,000 adolescents from 40 European countries, 26% of adolescents reported being involved in bullying, ranging from 8.6% to 45.2% for boys and 4.8% to 35.8% for girls.15 Variations in prevalence may be due to cultural differences in the acts of bullying or differences in interpretation of the term “bullying.”1,15

In the United States, a 2001 survey of more than 15,000 students in public and private schools (grades 6-10) asked the students about their involvement in bullying: 13% said they'd been a bully, 10.6% a victim, and 6.3% said they'd been both.6 There was no significant difference in the frequency of self-reported bullying among urban, suburban, or rural settings.

Despite efforts to educate the public about bullying and work with schools to intervene and prevent bullying, incidence remains largely unchanged. In 2013, the National Crime Victimization Survey reported that approximately 22% of adolescents ages 12 through 18 were victims of bullying.16 Similarly, the CDC's 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System reported that 20.2% of high school students experienced bullying on school property.17