Treatment options and precautions

As with isolated UTI, E coli is the most common pathogen in recurrent UTI. However, recurrent UTI is more likely than isolated UTI to result from other pathogens (odds ratio [OR]=1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0-2.26), such as Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Proteus, and Citrobacter.23 Since a patient’s recurrent UTI most likely arises from the same pathogen that caused the prior infection,8 start an antibiotic you know is effective against it. Additionally, take into account local resistance rates; antibiotic availability, cost, and adverse effects; and a patient’s drug allergies.

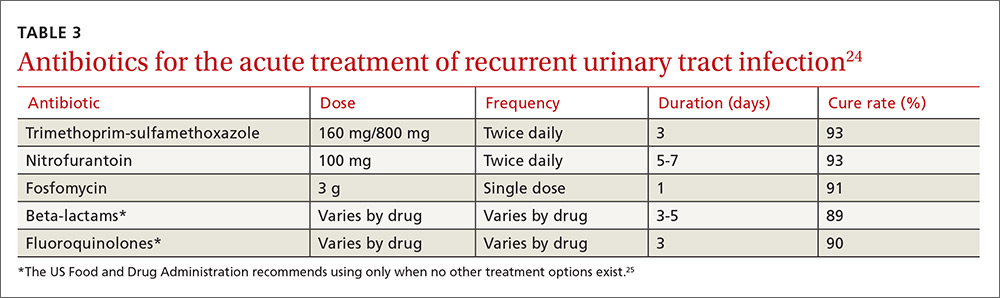

Preferred antibiotics. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), 160 mg/800 mg twice daily for 3 days, has long been the mainstay of treatment for uncomplicated UTI. Over recent years, however, resistance to TMP-SMX has increased. While it is still appropriate for many situations as first-line treatment, it is not recommended for empiric treatment if local resistance rates are higher than 20%.24 Nitrofurantoin 100 mg twice daily for 5 days has efficacy similar to that of TMP-SMX, but without significant bacterial resistance. While fosfomycin 3 g as a single dose is still recommended as first-line treatment, it is less effective than either TMP-SMX or nitrofurantoin. TABLE 324 summarizes these antibiotic choices and their efficacies.

Agents to avoid or use only as a last resort. For patients unable to take any of the drugs above, consider beta-lactam antibiotics, although they are typically less effective for this indication. While fluoroquinolones are very effective and have low (but rising) resistance rates, they are also associated with serious and potentially permanent adverse effects. As a result, on May 12, 2016, the Food and Drug Administration issued a Drug Safety Communication recommending that fluoroquinolones be used only in patients without other treatment options.24,25 Do not use ampicillin or amoxicillin, which lack effectiveness for this indication and are compromised by high levels of bacterial resistance.

Shorter course of treatment? When deciding on the length of treatment for recurrent UTI, remember that shorter antibiotic courses (3-5 days) are associated with similar rates of cure and progression to systemic infections as longer courses (7-10 days). Also, patients adhere better to the shorter treatment regimen and experience fewer adverse effects.26,27

Standing prescription? Studies have shown that women know when they have a UTI. Therefore, for women who experience recurrent UTI, consider giving them a standing prescription for antibiotics that they can initiate when symptoms arise (TABLE 324). Patient-initiated treatment yields similar rates of efficacy as physician-initiated treatment, while avoiding the adverse effects and costs associated with preventive strategies28 (which we’ll discuss in a moment).

Time for imaging and referral?

For patients with a high risk of complicated UTI or a surgically amenable condition, either ultrasound or computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast is appropriate to evaluate for anatomic anomalies. While CT is the more sensitive imaging study to identify anomalies, ultrasound is less expensive and minimizes radiation exposure and is therefore also appropriate.18

Consider referring patients to a urologist if they have an underlying condition that may be amenable to surgery, such as bladder outlet obstruction, cystoceles, urinary tract diverticula, fistulae, pelvic floor dysfunction, ureteral stricture, urolithiasis, or vesicoureteral reflux.18 Additional risk factors for complicated UTI, which warrant referral as outlined by the Canadian Urologic Association, are summarized in TABLE 2.18

2 weeks later…and it’s back? Finally, for women who experience recurrent symptoms within 2 weeks of completing treatment, obtain a urine culture with antibiotic sensitivities to ensure that the infecting organism is not one typically associated with urolithiasis (Proteus and Yersinia) and that it is susceptible to planned antibiotic therapy.18 Proteus and Yersinia are urease-positive bacteria that may cause stone formation in the urinary tract system. Evaluate any patient who has a UTI from either organism for urinary tract stones.

Prevention dos and don’ts

Popular myth suggests that recurrent UTIs are more common in patients who do not void after intercourse or who douche, consume caffeinated beverages, or wear non-cotton underwear. Research, however, has failed to show a relationship between any of these factors and recurrent UTIs.13,18 Physicians should therefore stop recommending that patients modify these behaviors to decrease recurrent infections.

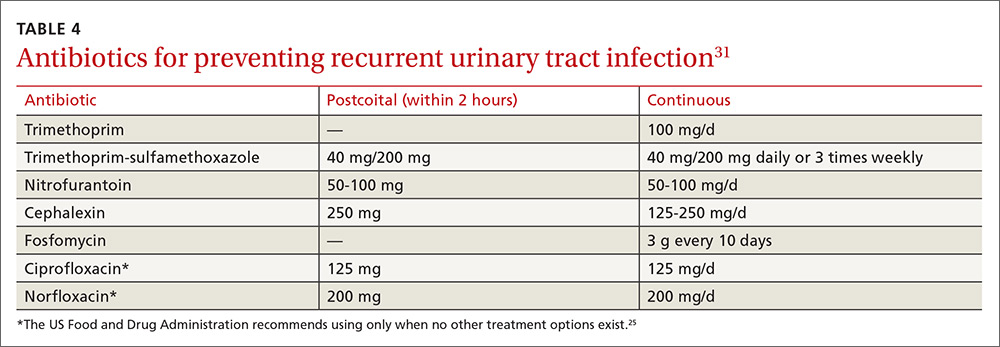

Antibiotic prophylaxis decreases the rate of recurrent UTI by 95%.29 It has been recommended for women who have had 2 or more UTIs in the past 6 months29 or 3 or more UTIs in the past year.30 Effective strategies to prevent recurrent UTI are low-dose continuous antibiotic prophylaxis or post-coital antibiotic prophylaxis.

While a test-of-cure culture is not typically recommended following treatment for uncomplicated UTI, you will want to obtain a confirmatory urine culture one to 2 weeks before starting low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis. Base your choice of antibiotic on known patient allergies and previous culture results. Agents typically used are trimethoprim, TMP-SMX, or nitrofurantoin31,32 (TABLE 431), none of which demonstrated superiority in a Cochrane review.33 Although the same review showed no optimal duration of treatment,33 6 to 24 months of treatment is usually recommended.29

A single dose of antibiotic following intercourse may be as effective as daily low-dose prophylaxis for women whose UTIs are related to sexual activity.34 Studies have shown that single doses of TMP-SMX, nitrofurantoin, cephalexin, or a fluoroquinolone (see earlier notes about FDA warning on fluoroquinolone use) are similarly effective in decreasing the rate of recurrence35,36 (TABLE 431).

Several non-pharmacologic strategies have been suggested for preventing recurrent UTI—eg, use of cranberry products, lactobacillus, vaginal estrogen in postmenopausal women, methenamine salts, and D-mannose.

A 2012 Cochrane review of 24 studies found that cranberry products were less effective in preventing recurrent UTIs than previously thought, with no statistically significant difference between women who took them and those who did not.37

Results have been mixed in using lactobacilli or probiotics to prevent recurrent UTIs. One study examining the use of lactobacilli to colonize the vaginal flora found a reduction in the number of recurrent infections in premenopausal women taking intravaginal lactobacillus over 12 months.38 A second study, involving postmenopausal women, found that those who were randomized to take lactobacillus tablets for 12 months had more frequent recurrences of UTIs than women randomized to take daily TMP-SMX.39 However, this last study was designed as a non-inferiority trial and its results do not negate the prior study’s findings. Additionally, vaginal estrogen, which is thought to work through colonization of the vagina with lactobacilli, has prevented recurrent UTIs in postmenopausal women.40