Staging liver disease is a prerequisite to treating HCV infection because the extent of liver fibrosis impacts not only prognosis, but also the choice of the treatment regimen and the duration of therapy. The traditional gold standard for diagnosing hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis has been a liver biopsy; however, a single 1.6-mm biopsy evaluates only a small portion of the liver and can miss affected liver parenchyma. In addition, a liver biopsy carries a small, but not inconsequential, risk of morbidity, and can be costly and complex to arrange.

Several noninvasive options are now available and are typically the preferred methods for staging liver disease. FibroSURE (LabCorp), for example, uses a peripheral venous blood sample and combines the patient’s age, gender, and 6 biochemical markers to generate a range of scores that correspond to the fibrosis component of the well-known METAVIR scoring system and correlate with results of liver biopsies.18,19 (The METAVIR system is a histology-based scoring system that grades fibrosis from F0 [no fibrosis] to F4 [cirrhosis].)

Noninvasive imaging studies assess for fibrosis more directly by assessing liver elasticity, either by ultrasound or magnetic resonance (MR) technology. The ultrasound modality FibroScan (Echosens) is currently the most widely available, although some data suggest the more expensive MR elastography has higher sensitivity (94% sensitive for METAVIR F2 or higher compared to 79% by FibroScan).20,21 While each of these modalities has limitations (eg, body habitus, availability), these tests allow stratification of patients into categories of low, moderate, and high risk for cirrhosis without the risks of biopsy.

A curable viral infection

HCV is one of the few curable chronic viral infections; unlike HBV and HIV, HCV does not create a long-term intra-nuclear reservoir. DAAs have cure rates of more than 95% for many HCV genotypes,22-24 allowing the possibility for dramatic reductions in prevalence in the decades to come.

Cure is defined by reaching a sustained virologic response (SVR), or absence of detectable viral load, 12 weeks after completion of therapy. Patients with HCV infection with advanced fibrosis who achieve SVR have shown benefits beyond improvement in liver function and histology. One large, multicenter, prospective study of 530 patients with chronic HCV, for example, found that those who achieved SVR experienced a 76% reduction in the risk of HCC and a 66% reduction in all-cause mortality (number needed to treat [NNT] was 5.8 to prevent one death or 6 to prevent one case of HCC in 10 years) compared to those without SVR.25 Other extrahepatic manifestations that impair quality of life, such as renal disease, autoimmune disease, and circulatory problems, are likewise reduced.25

Guidelines now recommend treating most patients with HCV infection

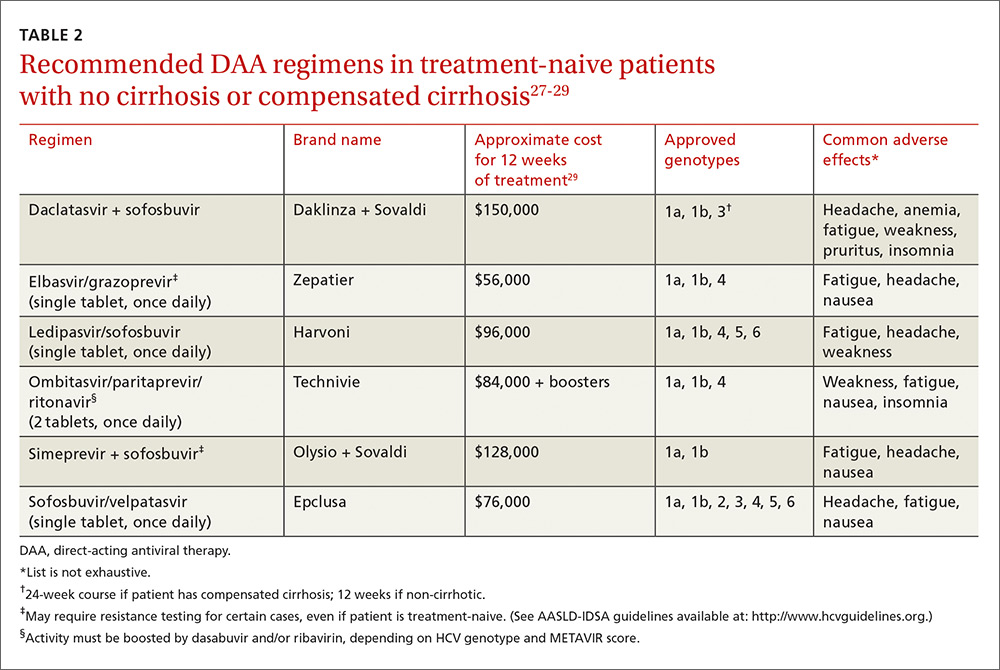

Until 2011, HCV treatment included the injectable immune-activating agent interferon and the non–HCV-specific antiviral ribavirin. This regimen had low SVR rates of 40% to 60% and adverse effects that were often intolerable.26 The advent of the first-generation HCV protease inhibitors in 2011 improved SVR rates, which have continued to improve exponentially with the development of combination therapy using DAAs (TABLE 227-29). (In order to stay up to date with the latest options for the treatment of HCV, see The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases treatment guidelines at: http://hcvguidelines.org.)

What the guidelines say. Due to the tolerability and efficacy of the new DAAs, current guidelines state that HCV treatment should be recommended to most patients with HCV infection—not just those with advanced disease.30 This is a major change from prior guidelines, which were based on more toxic and less effective regimens. Limited data from long-term cohort studies of patients using interferon-based regimens suggest that the benefits of SVR are greatest for those treated at early stages before significant fibrosis develops. At least one analysis involving over 4000 patients found, however, that this approach may be less cost-effective, with an NNT of 20 to prevent one death in 20 years.31

In practice, the decision to treat requires a discussion between the patient and provider, weighing the risks and benefits of treatment in the context of the patients’ comorbidities and overall life expectancy. Such a discussion must also include cost. Many insurance companies will still only cover antiviral therapy for patients with advanced fibrosis, but these restrictions are slowly lifting and are having significant implications for our health care system. By one estimate, treating all patients with HCV at current drug prices would cost approximately $250 billion—about one-tenth of the total annual health care costs in this country.32 As policies change and the cost of drug regimens decreases from increasing competition, access is likely to improve for the majority of Americans.