The number of childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) entering the adult health care system is increasing, a not-so-surprising trend when you consider that more than 80% of children and adolescents given a cancer diagnosis become long-term survivors.1 This patient population has a heightened risk for developing at least one chronic health problem, resulting from therapy. By the fourth decade of life, 88% of all CCSs will have a chronic condition,2 and about one-third develop a late effect that is either severe or life-threatening.3 In contrast to patients with many other pediatric chronic diseases that manifest at an early age and are progressive, CCSs are often physically well for many years, or decades, prior to their manifestation of late effects.4

Cancer survivorship has varying definitions; however, we define cancer survivorship as the phase of cancer care for individuals who have been diagnosed with cancer and have completed primary treatment for their disease.5 Cancer survivorship, which is becoming more widely acknowledged as a distinct and critically important phase of cancer care, includes:6

- “surveillance for recurrence,

- evaluation … and treatment of medical and psychosocial consequences of treatment,

- recommendations for screening for new primary cancers,

- health promotion recommendations, and

- provision of a written treatment summary and care plan to the patient and other health professionals.”

Although models of survivorship care vary, their common goal is to promote optimal health and well-being in cancer survivors, and to prevent and detect any health concerns that may be related to prior cancer diagnosis or treatment.

Some pediatric cancer survivors have not received recommended survivorship care because of a lack of insurance or limitations from pre-existing conditions.4,7 The Affordable Care Act may remove these barriers for many.8 Others, however, fail to receive such recommendations because national models of transition are lacking. Unique considerations for this population include their need to establish age appropriate, lifelong follow-up care (and education) from a primary care provider (PCP). Unfortunately, many CCSs become lost to follow-up and fail to receive recommended survivorship care when they discontinue the relationship with their pediatrician or family practitioner and their pediatric oncologist. Fewer than 25% of CCSs who have been successfully treated for cancer during childhood continue to be followed by a cancer center and are at risk for missing survivorship-focused care or recommended screening.4,9

PCPs are an invaluable link in helping CCSs to continue to receive recommended care and surveillance. However, PCPs experience barriers in providing cancer care because of a lack of timely and specific communication from oncologists and limited knowledge of guidelines and resources available to them.10 The purpose of this article is to share information with you, the family physician, about childhood cancer survivorship needs, available resources, and how partnering with pediatric oncologists may improve treatment and health outcomes for CCSs.

Providing for the future health of childhood cancer survivors

Numerous studies have outlined the myriad of potential late effects that CCSs may experience from disease and treatment.11,12 These effects can manifest at any time and can appear in virtually every body system from the central nervous system, to the lungs, heart, bones, and endocrine systems. CCSs' particular risk for late effects may result from many factors including cancer diagnosis, types of treatments (eg, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and stem-cell transplant), and dosages of medications, gender, and age at diagnosis.

Determining individual risk for late effects

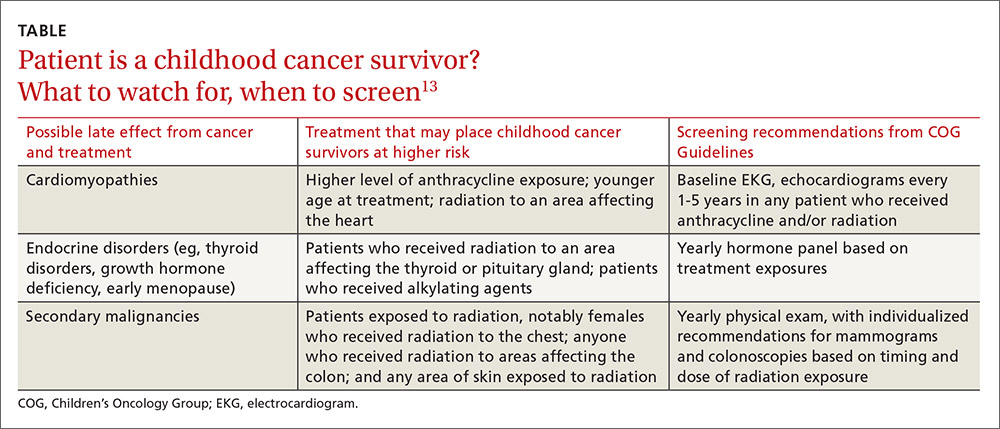

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) is the world’s largest organization devoted exclusively to childhood and adolescent cancer research, including the long-term health of cancer survivors. To help provide more individualized recommendations, COG has set forth risk-based, evidence-based, exposure-related clinical practice guidelines to offer recommendations for screening and management of late effects in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers.13 (These guidelines, Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers, are available at http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org.) The purpose of the guidelines is to standardize and enhance follow-up care for CCSs throughout their lifespan.13 To remain current, a multidisciplinary task force reviews and incorporates findings from the medical literature—including evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of recommended testing—into guideline revisions at least every 5 years.

Some of the most severe or life-threatening late effects include cardiomyopathies, endocrine disorders, and secondary malignancies (TABLE).13 Ongoing follow-up care is based on a survivor’s individual risk level and the frequency of lifelong recommended screening. The majority of patients will require yearly follow-up with additional testing, such as echocardiograms occurring as infrequently as every 2 to 5 years. Patients who received more intense therapy, such as hematopoietic stem-cell transplants, will require follow-up (often including annual echocardiograms, blood work, and a thorough physical exam) every 6 months to one year. Common testing and surveillance include blood pressure checks, urinalyses, thyroid function tests, lipid panels, echocardiograms, and electrocardiograms.