CASE › A 57-year-old man had been experiencing intermittent pain in his left ankle for the past 2.5 years. About 6 weeks before coming to our clinic, his symptoms became significantly worse after playing a pickup game of basketball. At the clinic visit, he reported no other recent injury or trauma to the leg. However, 15 years earlier he had fractured his left ankle and was treated conservatively with a short period in a cast followed by a course of physical therapy. After completing the physical therapy, he noted significant improvement, although he continued to have minor episodes of pain. He felt no instability or mechanical locking but did note a decreased ability to move the ankle. And it felt much stiffer than his right ankle.

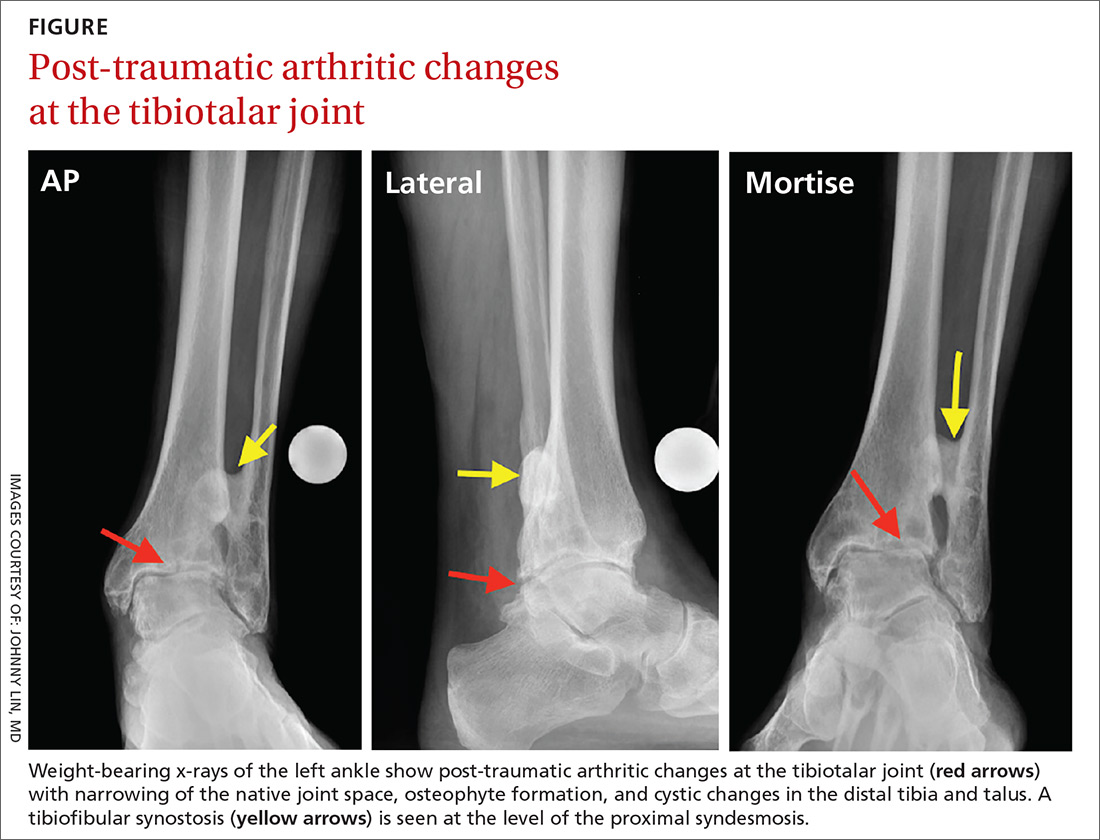

Examination of his left ankle revealed tenderness over the anterior aspect at the tibiotalar joint. He also exhibited decreased dorsiflexion and was unable to perform a toe raise. There was no tenderness over the major ligaments, and results of anterior drawer and talar tilt tests were normal. X-rays revealed tibiotalar joint arthritis (FIGURE).

How would you proceed if this were your patient?

Arthritis of the tibiotalar joint, which has an estimated prevalence of approximately 1%, occurs much less frequently than arthritis of the knee or hip joints.1 This low prevalence is primarily due to the ankle joint’s unique biomechanics and the features of the cartilage within the joint, including its thickness.2

Specifically, the hip and knee joints have greater degrees of freedom than the tibiotalar articulation, which is significantly constrained. The bony congruity between the talus, tibia, and fibula provides inherent stability to the ankle joint, thus protecting against primary osteoarthritis (OA).

Additionally, the large number of ligamentous structures and overall strength of the ligaments provide significant supplemental stability to the ankle joint articulation. Articular cartilage within the ankle joint is thicker than that of the knee and hip (1-1.7 mm). This cartilage also tends to retain its tensile strength with age, unlike cartilage in the hip; the ankle is therefore more resistant to age-related degeneration.3

Metabolic factors also protect against arthritis. Chondrocytes in the ankle are less responsive to inflammatory mediators, including interleukin-1 (IL-1), and therefore produce fewer matrix metalloproteinases.1,2,4 There are also fewer IL-1 receptors on ankle chondrocytes.

The role of trauma in ankle OA. Given the ankle joint’s inherent stability, the most common cause of ankle OA is trauma,4 mainly ankle fracture and, less commonly, ligamentous injury.5,6 Other rarer causes of ankle arthritis include primary OA, crystalline arthropathy, inflammatory disease, septic arthritis, neuroarthropathy, hemochromatosis, and ochronosis.

The ankle’s characteristics that protect it against primary OA may facilitate the pathogenesis of post-traumatic OA through 2 main mechanisms. First, direct trauma to the chondral surfaces can hasten the onset of progressive degeneration. Second, articular incongruity from a fracture can lead to insidious deterioration. The stiffer cartilage layer may be less adaptable to malalignment, and incongruity may cause secondary instability and chronic overloading. Ultimately, the joint breaks down with associated cartilage wear.6,7

The importance of the normal ankle’s congruity and stability became clear in the landmark study by Ramsey and colleagues,8 showing that the contact area between the talus and the tibia decreases as talar displacement increases laterally. This innate stability explains why the contact area of the ankle joint can bear loads similar to those of the hip and knee, yet does not experience primary OA nearly as often.

A stepwise diagnostic appraisal

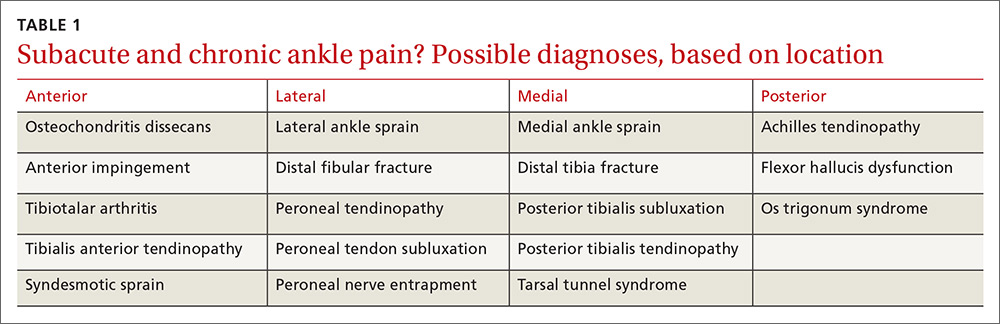

Ask these questions. Since most ankle pain results from trauma, ask about any recent or remote injury to the affected ankle. Knowing the type of injury that occurred and the exact treatment, if received, may shed light on the relationship between the injury and current symptoms. Acute traumatic events can cause fractures or injury to various soft-tissue structures traversing the ankle joint. Ankle ligament sprains or tendon strains may result after abnormal rotation of the foot. Alternatively, chronic overuse injuries may lead to tendinopathy in any of the tendons that control motion throughout the foot and ankle or degenerative changes within the tibiotalar joint. Knowing the exact location of pain may also help identify the pathology (TABLE 1).

The patient in our case had not suffered a recent injury, so it was important to learn as much as possible about his prior fracture. Was the injury treated conservatively or surgically? If management was conservative, the type and duration of treatment could offer clues to the mechanism underlying symptoms. If a patient has undergone surgery, knowledge of the exact procedure could suggest specific problems. For example, surgical fixation would likely indicate there was ankle instability, thus altering the normal biomechanics in the injured tibiotalar joint.

Other key questions to ask. Most patients with ankle pain also complain of limitations in their usual activities. Ask about the duration and type of pain and other symptoms. Also ask about the position of the foot and ankle when the pain is at its greatest, which will provide insight into likely areas of pathology. For example, if pain arises when the patient navigates uneven ground, subtalar pathology is highly likely. If the patient complains of pain while walking down stairs, suspect injury to the posterior (plantar flexed) ankle; pain while walking up stairs more likely indicates anterior (dorsiflexed) pathology.

Finally, ask about nonorthopedic medical problems and all medications being taken. Systemic conditions, too, can lead to ankle pain—eg, inflammatory arthropathies, infections, and crystalline arthropathy.

Physical examination. Observe the patient’s gait to assess any functional or range-of-motion limitations or abnormal loading throughout the foot and ankle.9 With the patient standing, evaluate any malalignment from the foot through the knees and to the hips. Evaluate the skin for any lesions, wounds, or evidence of trauma or surgery. Next, with the patient seated, examine carefully for neuropathy or vascular abnormalities. Evaluate the ankle’s range of motion and assess for any mechanical locking, clicking, or crepitus. Palpate all bony and ligamentous landmarks to reveal areas of tenderness or swelling. Perform anterior drawer and varus tilt tests to determine overall ligamentous stability of the ankle, and compare your findings with test results of the opposite, uninjured ankle.

Diagnostic imaging. Order weight-bearing radiographs of the foot and ankle. Including the foot allows you to identify additional potential concerns such as malalignment, deformity, or adjacent joint arthritis. Look particularly for joint space narrowing, malalignment, post-traumatic changes, or implanted hardware. Advanced imaging studies—computerized tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, bone scan—are reserved for cases that necessitate ruling out alternative diagnoses, or for preoperative evaluation by an orthopedic surgeon.